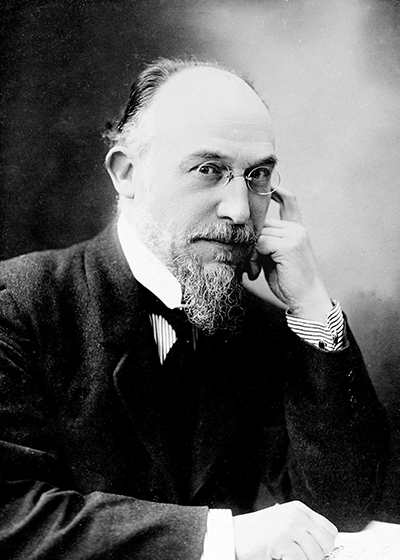

Erik Satie

orch. Claude Debussy

Born: May 17, 1866 in Honfleur, France.

Died: July 1, 1925 in Paris.

Orchestrated by Claude Debussy

Born: August 2, 1862 in St. Germain-en-Laye, near Paris.

Died: March 25, 1918 in Paris.

Gymnopédies Nos. 1 and 2

- Composed: composed for piano in 1888 and orchestrated in 1896

The American photographer and writer on music and literature Carl van Vechten gave the following description of Erik Satie: “a shy and genial fantasist, part-child, part-devil, part-faun,” who was “played on by Impressionism, Catholicism, Rosicrucianism, Pre-Raphaelitism, Theosophy, the camaraderie of the cabaret.” The character of Satie is as difficult to define as this sketch implies. He was friend and influence to the best creative minds in Paris during the decadent era surrounding the turn of the 20th century, yet he lived in cheerful poverty in a distant suburb. He was given to mysticism, but wrote music intended to arouse absolutely no passion. He ascribed fantastic, seemingly deprecatory titles to works (Pieces in the Form of a Pear, Five Grimaces, Desiccated Embryos, Posthumous Preludes) that offered one of the few viable alternatives to the pervasive tide of Wagnerism sweeping Europe at the end of the 19th century. The path he opened led the way not only toward the Impressionism of Debussy (a close friend for some 25 years) and Ravel, but also to the French avant-garde movement of Les Six, and, closer to our time, the minimalism of Terry Riley and Philip Glass.

Satie’s style was based on simplicity of technique and expression. At a time in the history of music when bigger (i.e., longer or louder or more cathartic or more complex) was assumed to be better, he proposed an art of quiet purity and emotional distance that led away from the Romanticism of the late 19th century to the clarity and restraint that had marked French thought in earlier times. The three Gymnopédies of 1888 were among his first works to translate these ideas into sound. In his book on the composer, Rollo H. Myers described them in the following manner: “In the Gymnopédies a slender, undulating melodic line is traced thinly over a rocking ‘pedal’ bass of shifting, delicately dissonant chords. The harmonic texture, modal in character, especially in the final cadences, is light and transparent; and the melody seems to have a strange aerial quality as if traced by floating gossamer threads suspended between earth and sky.” The first and third of the Gymnopédies were orchestrated by the composer’s friend Claude Debussy in 1896.

Of the unusual title of these little pieces, Klaus G. Roy wrote in the program notes of The Cleveland Orchestra, “[This] strange word literally means ‘culture in the raw,’ or ‘training without clothes.’... Apparently derived from the Greek word gymnopaidiai, paidia literally means ‘education’; we know it best from the word ‘pedagogy’; gymnos, ‘naked,’ is best known to us from the word ‘gymnasium.’” It has been suggested that these works were inspired by a decoration on an ancient Greek vase, or by a fresco of Puvis de Chavannes, or by Flaubert’s novel Salammbó. Whatever their source, it is clear that Satie meant to recall the tranquility and restrain associated with Classical civilization in these miniatures as an antithesis to the emotional flamboyance of his time. Writing for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Philip Hale noted the antique ancestors of the Gymnopédies. “The gymnopedia, the festival of ‘naked youths,’ was celebrated annually at Sparta in honor of Apollo Pythaeus, Artemis and Leto. The Spartan youths performed choruses and dances around the statues of these gods. The festival lasted several days. On the last there were choruses and dances in the theater. During the gymnastic exhibitions, songs and paeans to the deities were sung. The boys in the dances performed rhythmed movements, similar to some of the gymnastic exercises. During the festival there was great rejoicing, great merriment.”

Jean Cocteau, Satie’s friend and sometime collaborator, asked of these works, “In the welter of over-luscious, over-complex sonorities which the late 19th century so assiduously cultivated, what place could be found for anything quite so tenuous and transparent as those modest Gymnopédies whose limpid cadences evoke visions of barefooted dancers silhouetted on a Grecian urn?” The Impressionists and many other composers found their own answer to that question, and Patrick Gowers provided one for those who hear this music. In his article on the composer for the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, he wrote, “By stripping the music of all rhetoric Satie forces the listener to sharpen his responses, to concentrate and focus his sensitivity until the slightest shift becomes apparent.”

— Dr. Richard E. Rodda