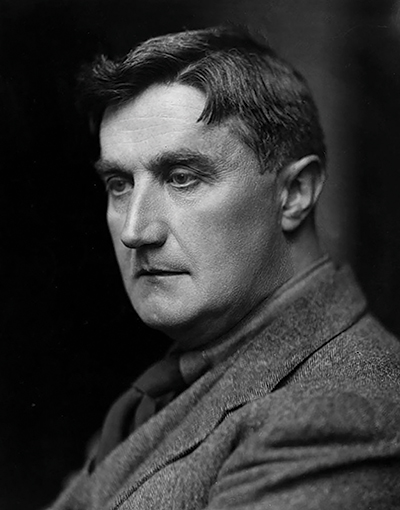

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born: October 12, 1872, Down Ampney, Gloucestershire

Died: August 26, 1958, London

Dona Nobis Pacem ("Grant Us Peace")

- Composed: 1934-1936

- Premiere: October 2, 1936 in Huddersfield, conducted by Albert Coates

- Instrumentation: SATB chorus, SB soloists, 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, chimes, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, tenor drum, triangle, harp, organ, strings

- May Festival Notable Performances: This is the first performance of Dona Nobis Pacem at the May Festival. CSO Subscription: November 2004, Robert Porco conducting; Janice Chandler, soprano; William McGraw, bass-baritone; May Festival Chorus, Robert Porco, director. May Festival Youth Chorus: March 2013, William White conducting; Amita Prakash, soprano; Brandon Morales, baritone; May Festival Youth Chorus, David Kirkendall, director; Lakota West High School Chorale, Anthony Nims, director; Taylor High School Senior Choir, Bret Albright, director.

- Duration: approx. 35 minutes

Vaughan Williams was an undergraduate at Cambridge in the 1890s when he was introduced to the poetry of Walt Whitman by fellow student Bertrand Russell. Whitman’s verses were enjoying a considerable vogue in England at that time, and Vaughan Williams was not immune to the lure of the American poet’s daring topics and experimental poetic structures, nor to his themes of mysticism, human dignity, love and freedom. The young musician acquired several editions of Leaves of Grass, including one small selection that he carried in his pocket, and as early as 1903—the year in which Delius brought out his Whitman-based Sea Drift—began composing a work for chorus and orchestra using the words of the American writer. As the basis of this creation, he chose passages from Leaves of Grass that philosophically likened the individual’s journey of life to an ocean voyage. Both the topic and its musical realization were imposing artistic challenges for Vaughan Williams, however, who, at age 31, had written only some songs, chamber pieces and small compositions for orchestra, and he was unable to finish the work at that time.

In 1905, Vaughan Williams turned his attention to another Whitman poem, “Whispers of Heavenly Death,” and set a passage from it as “A Song for Chorus and Orchestra” titled Toward the Unknown Region. The work was presented at the 1907 Leeds Festival with enough success to encourage him to return to his earlier Whitman piece, which he completed in 1910 as A Sea Symphony. The following year, he sketched a choral setting of Whitman’s “Dirge for Two Veterans,” but then declined to have it performed or published, and put it away for over two decades. It was not until 1934, the year after Hitler had begun his threat to European political stability by bullying his way to power in Germany, that Vaughan Williams returned to the “Dirge” and to the words of Walt Whitman. Although the composer’s output of the 1930s—the riotous Five Tudor Portraits, the comic opera The Poisoned Kiss, the colorful and ornate works for the coronation of George VI, the luminous Serenade to Music and the earliest sketches for the halcyon Fifth Symphony—remained largely in the pastoral nationalistic idiom principally associated with his music, the portentous Fourth Symphony of 1934 displayed a bristling modernity that many thought was influenced by the unsettling time of its creation. Although the composer asserted that there was nothing specifically programmatic about the Symphony (“I wrote it,” he said, “not as the picture of anything external—e.g., the state of Europe—but simply because it occurred to me like this. I can’t explain why.”), that his mind was drawn in the mid-1930s to foreboding thoughts of imminent war was confirmed by his revival of the “Dirge for Two Veterans” and the war-referencing text of the larger choral piece of 1934–36, Dona Nobis Pacem, of which it became part.

To create the text for his Dona Nobis Pacem, Vaughan Williams surrounded his revised setting of the “Dirge” with a collection of quotations matched to his own war-wary sentiments: a line from the Roman Catholic Mass (Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi: dona nobis pacem—“Lamb of God, who taketh away the sins of the world: grant us peace”), additional stanzas from Whitman, a brief excerpt from John Bright’s famous “Angel of Death” speech delivered to the House of Commons in 1855 during a debate on the Crimean War, and a number of biblical verses. Vaughan Williams organized Dona Nobis Pacem into six scenes that capture various aspects of war and its consequences. The work opens with the setting for soprano soloist and chorus of the Dona nobis pacem text, which begins introspectively but becomes a fervent supplication for peace as it proceeds. Before the entreaty can be answered, drum beats are heard as if from afar to lead without pause to a vehement interpretation of Whitman’s poem about the crushing of everyday life by war, Beat! beat! drums!—blow! bugles! blow! (It was a sign of those troubled times that the American composer Howard Hanson was creating his Songs from Drum Taps on exactly the same verses at just that time.) Following the horrible blast of conflict comes the Reconciliation, in which the baritone and chorus mourn those killed and maimed and pronounce some of Whitman’s most moving words—“For my enemy is dead, a man divine as myself is dead.” The soprano quietly recalls the prayerful Dona nobis pacem as a bridge to the Dirge for Two Veterans, given as a solemn dead-march for chorus and orchestra. The movement is subdued and lamenting for most of its length but rises to fury at the remembrance of the terrible hostilities that filled twin graves with the bodies of two veterans, a father and his son. The finale seeks assurance in the wake of the disturbing sentiments that have preceded it. A mighty hymnal tune of great optimism is launched in the middle of the movement, but the cantata ends not with a ringing choral affirmation of confidence in the durability of peace, but rather with the quiet and hopeful prayer of the soprano—“Grant us peace”—fading into silence.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda