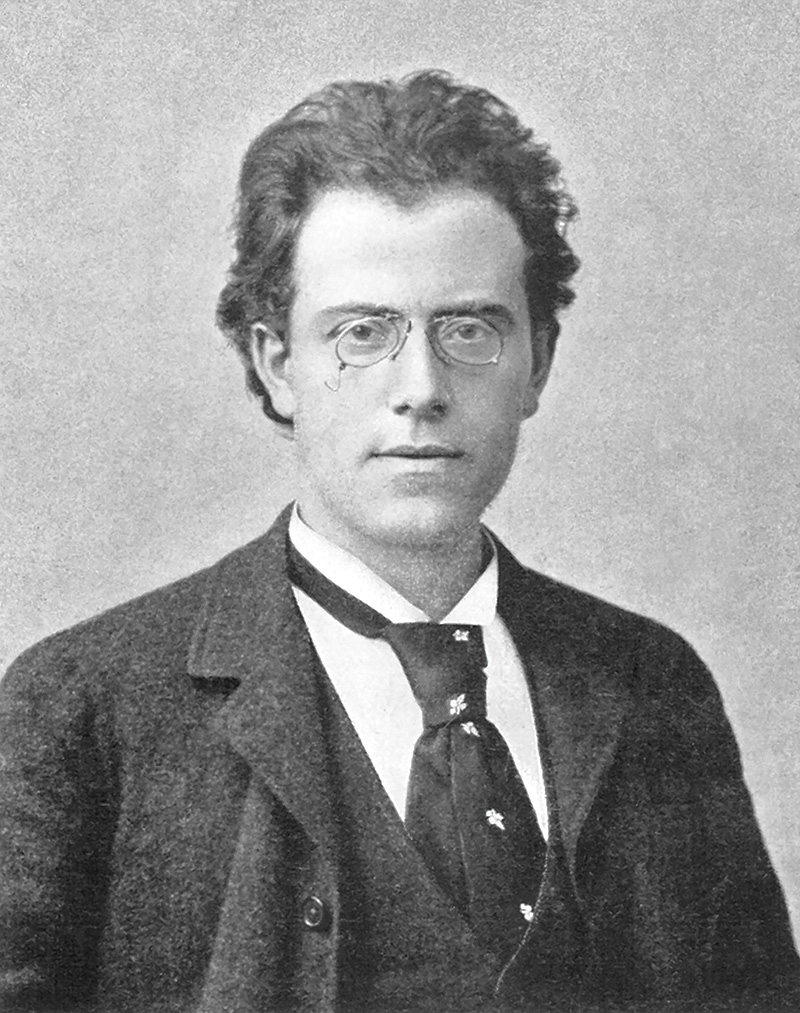

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, Kalischt, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, Vienna, Austria

Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Titan

- Composed: 1883–88, revised 1892–93

- Premiere: November 20, 1889 in Budapest, conducted by the composer

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1943, Eugene Goossens conducting

- Most Recent: January 2018, James Conlon conducting

- Instrumentation: 4 flutes (incl. 3 piccolos), 4 oboes (incl. English horn), 4 clarinets (incl. 2 E-flat clarinets and bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), 7 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, 2 timpani, bass drum, bass drum with attached cymbal, crash cymbals, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, harp, strings

- Duration: approx. 53 minutes

Although he did not marry until 1902, Mahler had a healthy interest in the opposite sex, and at least three love affairs touch upon the First Symphony. In 1880, he conceived a short-lived but ferocious passion for Josephine Poisl, the daughter of the postmaster in his boyhood home of Iglau, and she inspired from him three songs and a cantata after the Brothers Grimm Das klagende Lied (“Song of Lamentation”), which contributed thematic fragments to the gestation of the symphony. The second affair, which came early in 1884, was the spark that actually ignited the composition of the work. Johanna Richter possessed a numbing musical mediocrity alleviated by a pretty face, and it was because of an infatuation with this singer at the Cassel Opera, where Mahler was then conducting, that not only the First Symphony but also the Songs of a Wayfarer sprang to life. The third liaison, in 1887, came as the symphony was nearing completion. Mahler revived and reworked an opera by Carl Maria von Weber called Die drei Pintos (“The Three Pintos,” two being impostors of the title character) and was aided in the venture by the grandson of that composer, also named Carl. During the almost daily contact with the Weber family necessitated by the preparation of the work, Mahler fell in love with Carl’s wife, Marion. Mahler was serious enough to propose that he and Marion run away together, but she had a sudden change of heart and left Mahler standing, quite literally, at the train station. The emotional turbulence of all these encounters found its way into the First Symphony, especially the finale, but, looking back in 1896, Mahler put these experiences into a better perspective. “The Symphony,” he wrote, “begins where the love affair [with Johanna Richter] ends; it is based on the affair which preceded the Symphony in the emotional life of the composer. But the extrinsic experience became the occasion, not the message of the work.”

The symphony begins with an evocation of a verdant springtime filled with the natural call of the cuckoo (solo clarinet) and the man-made calls of the hunt (clarinets, then trumpets). The main theme, which enters softly in the cellos after the wonderfully descriptive introduction, is based on the second of the Songs of a Wayfarer, "Ging heut’ Morgen übers Feld" (“I Crossed the Meadow this Morn”). This engaging, folk-like melody, with its characteristic interval of a descending fourth, runs through much of the symphony to provide an aural link among its movements. The first movement is given over to this theme, combined with the spring sounds of the introduction, in a cheerful display of ebullient spirits into which creeps an occasional shudder of doubt.

The second movement, in a sturdy triple meter, is a dressed-up version of the Austrian peasant dance known as the Ländler, a type and style that finds its way into most of Mahler’s symphonies. The simple tonic–dominant accompaniment of the basses recalls the falling fourth of the opening movement, while the tune in the woodwinds resembles the Wayfarer song. The gentle central trio, ushered in by solo horn, makes use of the string glissandos that were integral to Mahler’s orchestral technique.

The third movement begins and ends with a lugubrious, minor-mode transformation of the European folk song known most widely by its French title, "Frère Jacques." It is heard initially in an eerie solo for muted string bass in its highest register, played above the tread of the timpani intoning the falling-fourth motive from the preceding movements. The middle of the movement contains a melody marked mit Parodie ("with parody," played “col legno” by the strings, i.e., tapping with the wood rather than the hair of the bow), and a simple, tender theme based on another melody from the Wayfarer songs, Die zwei blauen Augen (“The Two Blue Eyes”). The mock funeral march of this movement was inspired by a woodcut of Moritz von Schwind titled How the Animals Bury the Hunter from his Munich Picture Book for Children.

The finale, according to Bruno Walter, protégé and friend of the composer and himself a master conductor, is filled with “raging vehemence.” The stormy character of the beginning is maintained for much of the movement. Throughout, themes from earlier movements are heard again, with the hunting calls of the opening introduction given special prominence. The tempest is finally blown away by a great blast from the horns (“Bells in the air!” entreats Mahler) to usher in the triumphant ending of the work, a grand affirmation of joyous celebration.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda