Getting to Know Concertmaster Stefani Matsuo

by Hannah Edgar

The CSO’s de facto captain was born to play violin. Follow her path to the Orchestra, and learn why she says you can never be too prepared for an audition.

Stefani Matsuo is a Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra lifer. Before being appointed concertmaster in 2019, she was the orchestra’s associate concertmaster in the 2018–19 season, filling in as concertmaster on several occasions. Still before that, starting in 2015, she was a member of its second violin section. In total, Matsuo has spent just one year of her professional career not playing in Cincinnati—as a member of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra from 2014 to 2015.

“It was a great way to start my career,” Matsuo told Fanfare, calling from the living room of her Park Hills, KY home, five minutes from Music Hall. “I sat in these positions in youth orchestra and in school, but a professional orchestra is a completely different story. People had already welcomed me with open arms as a section violinist. That comfort of already being part of this family was so nice.”

The CSO doesn’t just feel like family to Matsuo: it is family. She’s been married to CSO section cellist Hiro Matsuo since 2016; they met at a chamber music reading party as graduate students at Juilliard. (“As nerdy as that sounds,” Matsuo recalls with a laugh.) They commuted two hours to see one another while she was in Indianapolis and he in the CSO, initially in a one-year position. The couple also plays together—if Stefani’s schedule allows—in concert:nova, a venturesome local chamber music series.

Having music around 24/7 is nothing new for Matsuo, 35. Growing up in North Carolina, she watched her mother, also a violinist, play in the Greensboro Symphony. Her little brothers, CJ and Andrew, play cello and viola, rounding out a family quartet that reunites over the holidays. Her father, a human resources director, doesn’t play, but he was her biggest cheerleader, happily chauffeuring the kids to their many lessons and rehearsals.

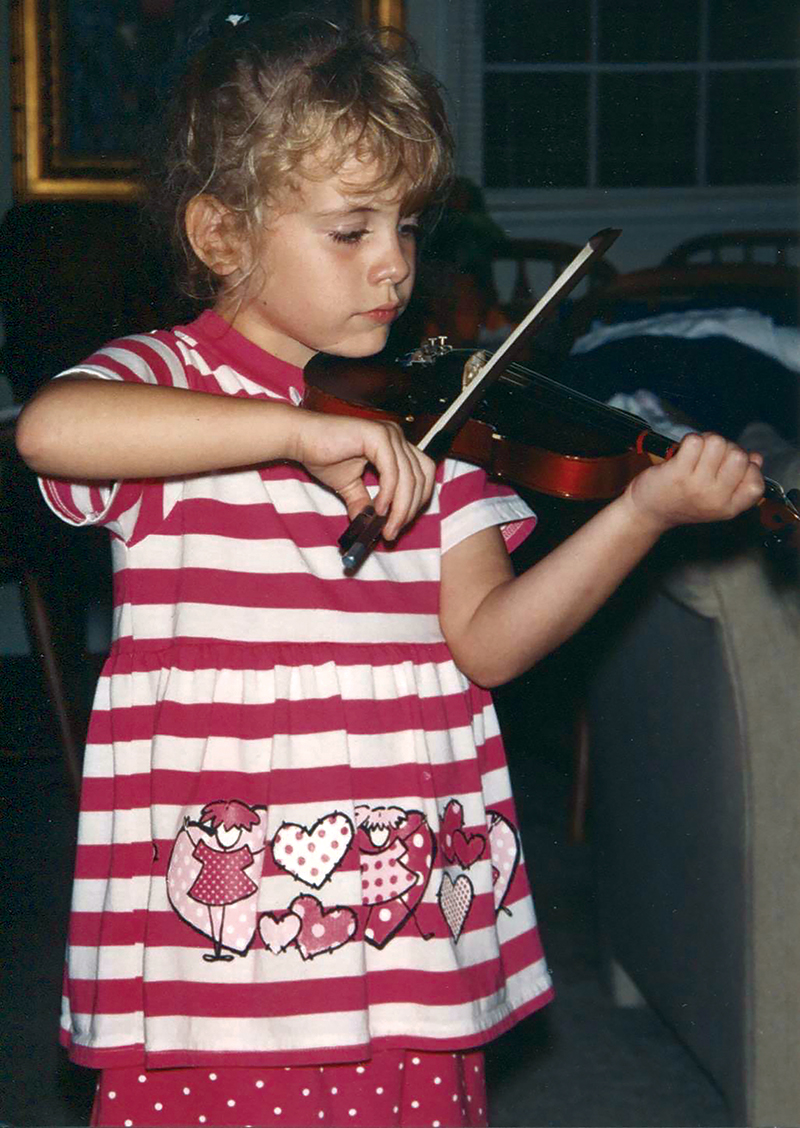

Stefani with her first tiny violin

Stefani with her first tiny violin

Even among super-virtuosos, Matsuo started on violin preternaturally early. Watching her mom’s violin students file in and out of the house, baby Stefani assumed “everybody played violin—it was just something people did.” Per family lore, Matsuo asked for her own violin at 15 months (insofar as a 15-month-old can ask for anything). Her mom got her a toy violin, but that was short-lived: Matsuo cried when she realized it didn’t make any sound.

“She was like, ‘Okay, I guess we’re getting a 1/32-size violin,’” Matsuo says.

Those minuscule starter violins are only a foot long and mostly for pedagogical purposes, not performance—any repertoire played on them sounds like an Alvin and the Chipmunks dub. No matter: Matsuo was “in heaven.” She cried—again—when her parents asked her to put the violin away. The intensity with which Matsuo approached the instrument left even her violinist mother flummoxed.

Stefani with her 1/16-size violin.

Stefani with her 1/16-size violin.

“I was the kid that was like, ‘I messed up this part in the competition, I need to go home and practice it 50 times!’ My parents were like, ‘How about we get some ice cream first?’” she says.

Like so many violinists, Matsuo absorbed the sounds and styles of big-name virtuosi. She admired the Romantic, “chocolaty” tone of David Oistrakh and Itzhak Perlman and the finesse of Gil Shaham and Midori. As a child of the ’90s, however, Matsuo didn’t need to look to previous generations for musical idols. She came of age at a time when Sarah Chang and Hilary Hahn were selling out concert halls; a solo appearance in Greensboro by violinist/violist Yura Lee, just a couple years older than her, was especially transformative. Growing up alongside those young prodigies only pushed Matsuo to work harder.

“I probably listened to Sarah Chang’s Carmen Fantasy CD on repeat until it didn’t work anymore,” Matsuo recalls.

Matsuo’s mother was her main violin teacher throughout most of her childhood. Later, however, she wisely suspected her soon-to-be-teenage daughter might take instruction better from a different teacher. She sent Stefani to study with Sarah Johnson at the nearby University of North Carolina School for the Arts (UNCSA), where she remained through high school. Matsuo also joined the school’s orchestra and the Greensboro Youth Symphony, where she cut her teeth on orchestral repertoire.

Stefani rehearsing Christmas carols with her mother.

Stefani rehearsing Christmas carols with her mother.

Foreshadowing her eventual career in Cincinnati, Matsuo tried on several roles in the violin section during those years: section player, principal second, assistant and associate concertmaster, and, finally, concertmaster, the highest-pressure role of them all. The concertmaster acts not just as the leader of the first violins—they take most important section violin solos—but as a key intermediary between orchestra musicians and the conductor. “You work with them behind the scenes to help bring their vision to life with the orchestra,” Matsuo says.

Stefani at age 6, soloing with an orchestra for the first time.

Stefani at age 6, soloing with an orchestra for the first time.

On the flip side, if the conductor’s leadership flags or is unclear, orchestra musicians will look to the concertmaster as a safety net. Other less glamorous, but no less crucial, tasks assumed by the concertmaster include determining bowings for the first violins (and sometimes advising on those of the other string sections), serving on audition panels for new members, and cuing the tuning process at the head of concerts.

“I was really glad to be able to start learning orchestra etiquette from a young age: what it means to be a good stand partner, and what it means to really prepare for rehearsals. It helped me learn the ropes of what’s expected of different positions [in the orchestra],” Matsuo says.

One such early learning experience came during her time at UNCSA. The young violinist had never taken an audition before arriving at UNCSA, but the orchestra director—an old-school conductor who had taught there for decades—called in musicians during a concert cycle rehearsing Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 in order to assess their skills. For these assessments, the conductor could test students on anything across the whole concert program, but Matsuo’s excerpt was the symphony’s final Allegro movement—among the most common audition excerpts in the literature.

Stefani performing for her classmates with her mother, Karen Collins.

Stefani performing for her classmates with her mother, Karen Collins.

As the youngest in the orchestra, Matsuo already felt compelled to be über-prepared. She practiced and listened to recordings in the library for hours on end. But no amount of preparation could have equipped her for what the conductor asked her to do during her assessment: close her music, push the stand down and play part of the last movement from memory. Thankfully, Matsuo had practiced enough that she passed.

In Matsuo’s recollection, the conductor “thought it was hilarious.” But in hindsight, she suspects he wasn’t just being sadistic. “He obviously knew it was my first audition, and he wanted to see how I would take the pressure. Moving forward with other auditions, it taught me to prepare at an even higher level.”

It has paid off. Matsuo attended the Cleveland Institute of Music for her undergraduate studies, studying with Paul Kantor, and Juilliard for her master’s degree, studying with Sylvia Rosenberg. She gained additional experience sitting concertmaster in both schools’ orchestras. All the while, Matsuo’s very first teacher—her mother—was always just a call away if she had a technique question or needed another set of ears for feedback on her playing.

At each school, Matsuo encountered very different styles of pedagogy than she had with her teacher in North Carolina. Sarah Johnson, her first teacher, helped her cultivate a European sound and led the studio in a “Kreisler Project,” in which students prepared a different piece by the great violinist–composer every week. They balanced that with a progression through the core violin repertoire—a hallmark of Johnson’s own teacher, the legendary Ivan Galamian.

Stefani pictured with childhood teacher Sarah Johnson and conductor Bruce Kiesling, following her performance of the Tchaikovsky concerto.

Stefani pictured with childhood teacher Sarah Johnson and conductor Bruce Kiesling, following her performance of the Tchaikovsky concerto.

In Cleveland, Kantor’s approach to his studio was more bespoke. Studio classes were almost Socratic, with students sharing valuable nuggets gleaned from their own lessons in their feedback. “It wasn’t a cookie cutter studio. He really helped me learn how to analyze my playing when I was on my own in a practice room…. The end product was always your musical idea,” she remembers.

Rosenberg, at Juilliard, was more of a “kick in the pants.” She built on Johnson’s pursuit of an old-world sound and personality, even if her one-liners could be brutal. Matsuo once worked with Rosenberg on a Schubert Rondo ahead of a big competition. “She said, ‘Honey, just hand me your violin.’ She played it, then said, ‘That’s the charm that Schubert needs.’ She took my idea of what it meant to be prepared for any concert, competition or even my weekly lesson to a completely different level.”

Years later, after Matsuo had earned tenure in the CSO, concertmaster emeritus Timothy Lees announced his retirement from the orchestra after 20 years. Concertmaster positions, especially at an orchestra as prestigious as Cincinnati’s, attract an international applicant pool. Internal hires aren’t unheard of, but they’ve become increasingly few and far between in the rarefied orchestra world.

Against the odds, Matsuo, newly appointed associate concertmaster just the season before, decided to throw her hat in the ring. She beat out an international candidate pool to win the job.

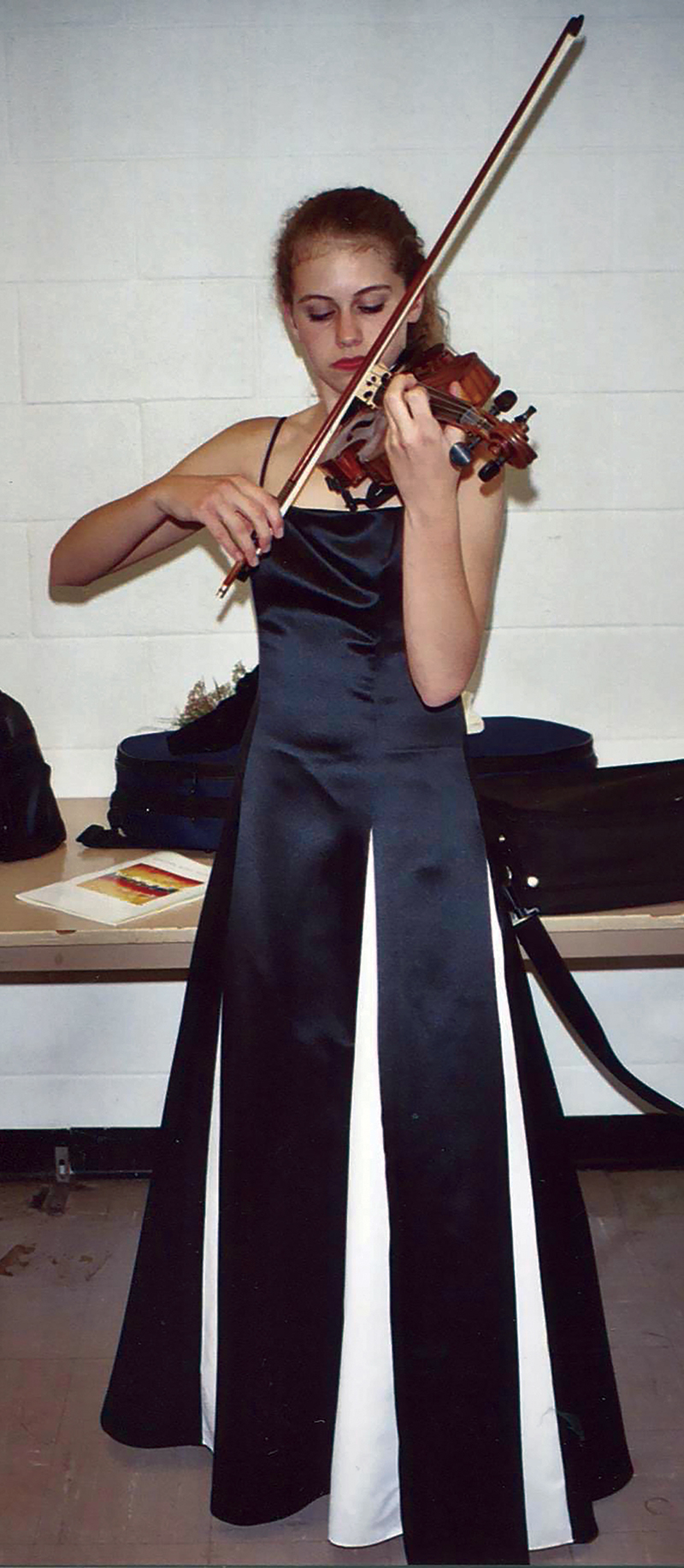

Stefani warming up before a solo performance with orchestra.

Stefani warming up before a solo performance with orchestra.

“Joining as a second violinist, I already knew this was an orchestra full of great, extremely kind people that I really loved being around and playing with. So, when each of these positions opened up, I thought, ‘I love being here, this audition’s happening, why not? I have nothing to lose.’ Then it somehow worked out,” Matsuo says.

As for her own very musical family, the Matsuos have two children: Hana, 2, and Noah, born over the summer. Matsuo insists she doesn’t want to push either into music—but so far, Hana is very much her mother’s daughter. She plays the very same teensy-tiny 1/32 violin Matsuo started on, decades ago.

So far, though, Hana would rather play it like a cello than a violin—Hiro 1, Stefani 0. For now, Matsuo calls her their “cellist–violinist.”

“She’s interested. It just depends on which instrument she’s actually interested in,” Matsuo says.

Stefani Matsuo performs Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4 with conductor Louis Langrée and the CSO.

Stefani Matsuo performs Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4 with conductor Louis Langrée and the CSO.