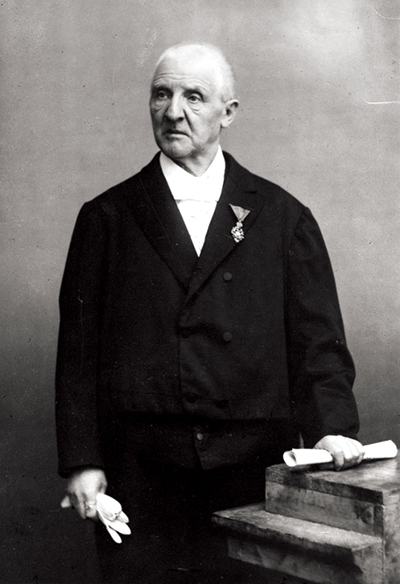

Anton Bruckner

Born: September 4, 1824, in Ansfelden, Austria

Died: October 11, 1896, in Vienna

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor

- Composed: completed in 1894

- Premiere: April 1932, Munich, Siegmund von Hausegger conducting

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: April 1923, Fritz Reiner conducting

- Most Recent: January 2008, Paavo Järvi conducting

- Recording: Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor released in 1992, Jesús López Cobos conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 3 oboes, 3 clarinets, 3 bassoons, 8 horns (incl. 4 Wagner tubas), 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 63 minutes

Anton Bruckner grew up in the small village of Ansfelden in Upper Austria, where his father and grandfather had both worked as schoolmasters. As a young boy, he sang in choir and learned to play the organ. When his father died in 1837, the 13-year-old Bruckner was taken in by the Augustinian monastery of Saint Florian, near Linz, and became a choirboy. He later followed the family tradition and trained in Linz to become a schoolteacher. In 1845 he returned to Saint Florian, where he taught for 10 years. During this time, he played organ at the abbey church and composed choral music for use within the community. He eventually became frustrated by the limitations of his job, and the growing isolation he felt at the monastery pushed him to look farther afield.

He applied for and won the position of organist at the cathedral in Linz, a job that allowed him to let go of teaching and pursue music full time. Bruckner lacked confidence as a composer—an insecurity he dealt with his entire life—and so began lessons in counterpoint and harmony with the Viennese teacher Simon Sechter. Over the course of six years, Bruckner studied with Sechter, traveling to Vienna and corresponding through letters. He became a perpetual student, still not ready to explore his own musical expression and instead finding teachers in Linz to teach him orchestration, form and analysis.

Finally, in his 40s, Bruckner began to compose his first symphony and completed three choral Masses. His devout Catholicism led him to focus on writing music for sacred texts, a genre that he specialized in alongside his growing talent for large-scale symphonies. Throughout his life, he struggled with doubt, depression and fierce opposition from critics. He was an awkward man who held on to his rural habits and dress even after moving to Vienna to succeed his former teacher Simon Sechter as professor of music at the Vienna Conservatory.

When Bruckner first came to Vienna, the strong-willed and opinionated critics and audiences of the city were divided between the adherents of the traditional style of Johannes Brahms and the modernity of Richard Wagner. Bruckner admired Wagner but did not see himself as a devoted disciple by any means. The powerful music critic Eduard Hanslick, a staunch supporter of Brahms, widely scorned Bruckner’s ideas on the future of the symphony and used his influence to block Bruckner from gaining traction in his career. After years of effort, Bruckner reached a turning point with the premiere of his Seventh Symphony in 1884, which enjoyed immediate success with the public—a welcome relief for the beleaguered composer.

As he worked on his Ninth Symphony, Bruckner humbly accepted a new level of fame and, in 1886, was honored by the Emperor with the Order of Franz Joseph. Work on his final symphony continued for seven years until his death in 1896 left it unfinished. He was in poor health, suffering from a heart condition, progressive liver failure and mental decline. Knowing the Ninth would be his last symphony, he told a visitor that this would be his masterpiece, saying “I just ask God that he’ll let me live until it’s done.” He completed three movements and was at work on the finale on the day he died, when, after sitting at his piano all morning, he took tea and went to bed complaining of a cold. He passed away peacefully in his sleep.

Ferdinand Löwe, a former pupil of Brucker, had decided after his teacher’s death to make what he thought of as necessary changes to the Ninth’s score. Löwe conducted the revised symphony in 1903 and neglected to reveal the fact that he had tinkered with it. After years of performances using the altered score, scholars and conductors questioned its authenticity and the truth came out. In a special concert in Munich on April 2, 1932, Siegmund von Hausegger conducted both versions—the by then familiar Löwe version followed by Bruckner’s original score—of the symphony side by side. The unaltered Bruckner score was clearly superior and immediately recognized as the valid and true version.

Bruckner dedicated his Symphony No. 9 “to beloved God” and gave it the same key signature—D minor—as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The opening bars also clearly point to Beethoven as the sound emerges from nothingness into the full force of orchestral splendor. After a long descending pizzicato line ends the opening statement, a new theme in A major begins and features a lovely melody played by the violins. This theme rises, falls and rises again before a third theme is introduced in a more solemn mood. These three themes make up the material for the first movement as they are each restated and developed in turn.

In another likeness to Beethoven’s Ninth, the second movement is in the form of a scherzo. Bruckner breaks from the traditional idea of a scherzo as being filled with lightheartedness and humor. Instead, this movement is menacing and dissonant. After a soft beginning of pizzicato strings and sustained notes in the winds, the entire orchestra erupts into fierce thrusting chords, quickly establishing the movement’s brutal nature. Extremes abound as the oboe enters with an innocent melody, setting off a chain of delicate phrases until the driving chords return. The center of the movement contains a faster trio section in a sunny major key that takes off with rustling strings, breezy flutes and light timpani strikes. The opening material returns, foreboding as ever, to close out the movement.

The final Adagio is Bruckner’s farewell to the world and begins with an anguished leap in the violins. The rest of the ensemble slowly joins in and comes to rest on an exquisite, shimmering E-major chord. In these measures, Bruckner is alluding to Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal, and the motif associated with the Holy Grail. In doing so, he also alludes to the importance of his own Christian faith. From the stillness, the cellos and basses enter with a darker tone, gathering forces and building in intensity. A warm second theme is introduced by the violins and then the cellos. Another silence brings the reentrance of the first anguished theme and the tension builds slowly toward a final climax of extreme dissonance and force. The movement ends in quietness with Bruckner taking a moment to look back. Wagner tubas quote the first theme of his Eighth Symphony and horns recall the first phrase of his Seventh before closing on a hushed and peaceful E-major chord.

—Catherine Case