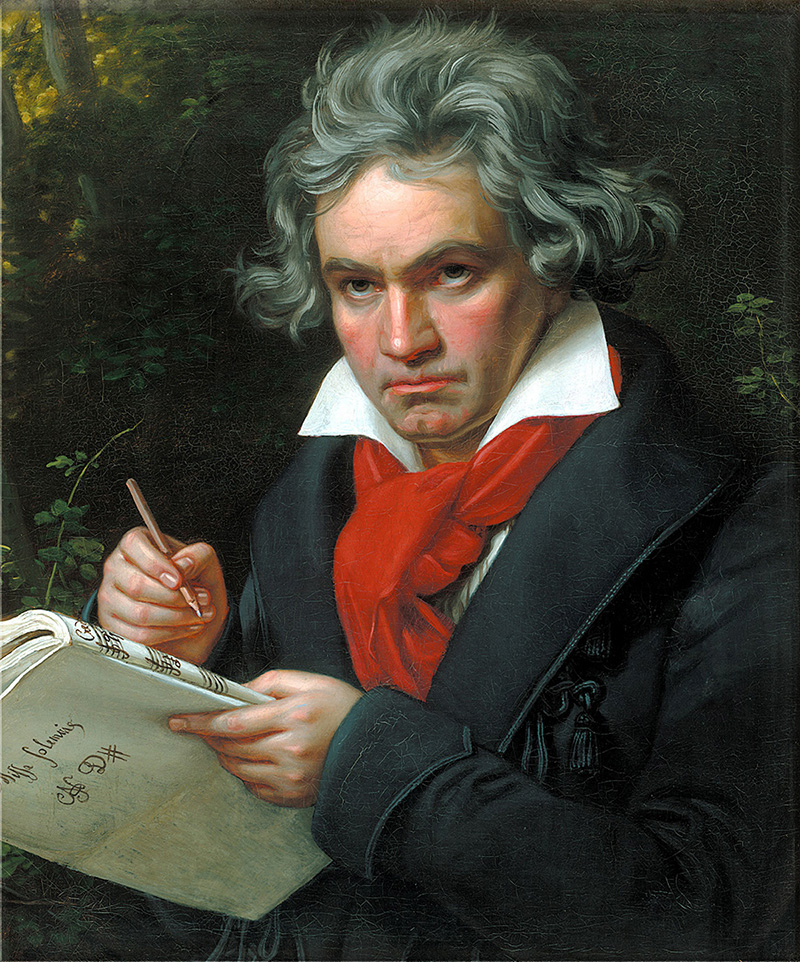

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Concerto No. 4 in G Major for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 58

- Composed: 1804-06

- Premiere: March 5, 1807 at the palace of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz in Vienna, with the composer as soloist

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1905, Frank Van der Stucken conducting; Josef Hofmann, piano

- Most Recent: October 2023, Ramón Tebar conducting; Jonathan Biss, piano

- Most Recent CSO Subscription: February 2020, Louis Langrée conducting; Inon Barnatan, piano

- Instrumentation: solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 34 minutes

The Napoleonic juggernaut twice overran the city of Vienna. The first occupation began on November 13, 1805, less than a month after the Austrian armies had been soundly trounced by the French legions at the Battle of Ulm on October 20. Although the entry into Vienna was peaceful, the Viennese had to pay dearly for the earlier defeat in punishing taxes, restricted freedoms and inadequate food supplies. On December 28, following Napoleon’s fearsome victory at Austerlitz that forced the Austrian government into capitulation, the Little General left Vienna. He returned in May 1809, this time with cannon and cavalry sufficient to subdue the city by force, creating conditions that were worse than those during the previous occupation. As part of his booty and in an attempt to ally the royal houses of France and Austria, Napoleon married Marie Louise, the 18-year-old daughter of Austrian Emperor Franz. She became the successor to his first wife, Josephine, whom he divorced because she was unable to bear a child. It was to be five years—1814—before the Corsican was finally defeated and Emperor Franz returned to Vienna, riding triumphantly through the streets of the city on a huge, white Lipizzaner.

Such soul-troubling times would seem to be antithetical to the production of great art, yet for Beethoven, that ferocious libertarian, those years were the most productive of his life. Hardly had he begun one work before another appeared on his desk, and his friends recalled that he labored on several scores simultaneously during that period. Sketches for many of the works appear intertwined in his notebooks, and an exact chronology for most of the works from 1805 to 1810 is impossible. So close were the dates of completion of the fifth and sixth symphonies, for example, that their numbers were reversed when they were given their premieres on the same giant concert as the Fourth Concerto. Between Fidelio, which was in its last week of rehearsal when Napoleon entered Vienna in 1805, and the music for Egmont, finished shortly after the second invasion, Beethoven composed the following major works: “Appassionata” Sonata, Op. 57; violin concerto; fourth and fifth piano concertos; three quartets of Op. 59; Leonore Overture No. 3; Coriolan Overture; fourth, fifth and sixth symphonies; two piano trios (Op. 70); “Les Adieux” Sonata, Op. 81a; and many smaller songs, chamber works and piano compositions. It is a stunning record of accomplishment virtually unmatched in the history of music.

Of the nature of the Fourth Concerto, American musicologist Milton Cross wrote, “[Here] the piano concerto once and for all shakes itself loose from the 18th century. Virtuosity no longer concerns Beethoven at all; his artistic aim here, as in his symphonies and quartets, is the expression of deeply poetic and introspective thoughts.” The mood is established immediately at the outset by a hushed, prefatory phrase for the soloist. The form of the movement, vast yet intimate, begins to unfold with the ensuing orchestral introduction, which presents the rich thematic material: the pregnant main theme, with its small intervals and repeated notes; the secondary themes—a melancholy strain with an arch shape and a grand melody with wide leaps; and a closing theme of descending scales. The soloist re-enters to decorate the themes with elaborate figurations. The central development section is haunted by the rhythmic figuration of the main theme (three short notes and an accented note). The recapitulation returns the themes and allows an opportunity for a cadenza (Beethoven composed two for this movement) before a glistening coda closes the movement.

The second movement starkly opposes two musical forces—the stern, unison summons of the strings and the gentle, touching replies of the piano. Franz Liszt compared this music to Orpheus taming the Furies, and the simile is warranted, since both Liszt and Beethoven traced their visions to the magnificent scene in Gluck’s Orfeo where Orpheus’ music charms the very fiends of Hell. In the concerto, the strings are eventually subdued by the entreaties of the piano, which then gives forth a wistful little song filled with quivering trills. After only the briefest pause, a high-spirited and long-limbed rondo-finale is launched by the strings to bring the concerto to a stirring close.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda