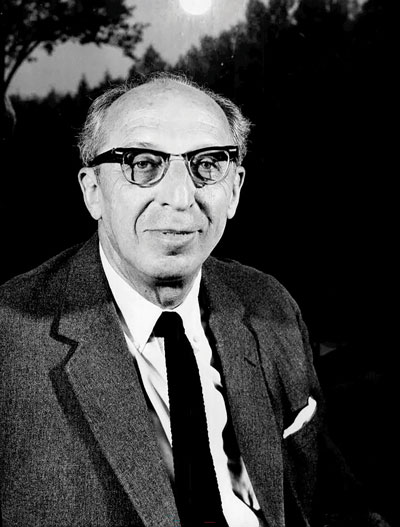

Aaron Copland

Born: November 14, 1900, New York, NY

Died: December 2, 1990, Sleepy Hollow, NY

Symphony No. 3

- Composed: 1944-46

- Premiere: October 18, 1946, Serge Koussevitzky conducting the Boston Symphony OrchestraDedicatee: Natalie Koussevitsky

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1964, Aaron Copland conducting

- Most Recent: May 2013, Robert Spano conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), piccolo, 3 oboes (incl. English horn), 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, anvil, bass drum, chimes, claves, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, ratchet, slapstick, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tenor drum, triangle, wood block, xylophone, 2 harps, celeste, piano, strings

- Duration: approx. 43 minutes

Around the conclusion of World War II, American composer Aaron Copland sought to capture the spirit of optimism burgeoning across his country. Copland’s grand statement came in the shape of what many have long viewed as the apex of instrumental composition, the symphony. Pressure from colleagues and the public was mounting on America’s most prominent composer to write an extended piece in the form—his contemporaries, after all, had been vigorously producing fine works in the genre over the preceding decades. In March 1944, Copland accepted a commission from the Koussevitsky Music Foundation to produce such a work. Yet, likely aware of his stature on the heels of publicly successful ballet scores and lucrative film work, Copland remained quiet while he worked on the symphony, only sharing his plans with those closest to him. His discretion casts a humorous light on a September 1944 letter he received from American composer Samuel Barber, who wrote from Italy: “I hope you will knuckle down to a good symphony. We deserve it of you, and your career is all set for it. Forza!” In October of that year, composer William Schuman caught wind of the commission and wrote to Copland, “I gather your Koussie commission is the long-awaited symphony. It better be.” In truth, as musicologist Elizabeth B. Crist has found, the symphony’s seeds had been germinating for some four years at that point. Copland’s earnest work on the piece from 1944 to 1946 straddled the transition from war time through the D-Day invasion and into the prosperous early post-war years, circumstances that inspired Copland to write in a manner reflecting his country’s positive spirit.

As many listeners have noted since its premiere, the Third Symphony exhibits many of the styles for which Copland had come to be known, up to the 1940s: jazz influences heard in Music for the Theatre (1925), austere abstraction in the Piano Sonata (1939–41), and his most famous trademark “populism” in the ballets Billy the Kid (1938) or Appalachian Spring (1943–44) and of film scores like Of Mice and Men (1939). While encapsulating these differing musical characters, the Third Symphony’s fusion speaks to Copland’s ability to move fluidly between styles throughout his career, never wholly confined to one or another in neat successive periods. Copland averred that any reference to folkism or jazz in the symphony was “purely unconscious,” but listeners may detect echoes throughout, some subtler (like general “open prairie”-sounding music or a late quotation of the cowboy tune “Goodbye Old Paint”) and one overt: the reuse of the composer’s earlier Fanfare for the Common Man. The Fanfare had been composed in 1942 and premiered in March 1943 on commission from Eugene Goossens and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra as part of a group of war-time curtain-raisers, and Copland found it suitable as a final word to capture the spirit he intended to project in the symphony.

The electrifying Fanfare finale stands like an orator’s skilled climax to a long rhetorical build. The first movement begins more humbly, however, with gently sighing strings and woodwinds that invite listeners to lean in. These ideas expand and broaden to new and increasingly bold ideas over the course of the movement’s first section, momentarily culminating with forceful brass. A brief, rhythmically enlivened middle provides contrast before the mood returns to the opening section’s string figures. In full circle, those opening sighs reappear at the symphony’s end, bringing familiar signposts to the piece’s sophisticated structure. Since Copland intended the symphony to capture a post-war spirit, we might think of the late recall of these more plaintive musical ideas as reminders of the grave circumstances still ongoing when the composer accepted the symphony’s commission.

The symphony’s second and third movements throw one another into relief. The second movement, a scherzo, is framed by sections of jocular, rhythmically driven motifs, complemented by a lyrical middle section that points ahead to the third movement. The spare-sounding beginning of the third movement invokes textures one might hear in Mahler’s symphonies, in which small chamber ensembles within the orchestra sometimes speak to one another in counterpoint. Or else Copland’s brittle violins at the third movement’s outset might call to mind the beginning fragility of Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta. The third movement mirrors the second with its tripartite construction, but here the slow outer sections are foiled by a livelier middle. (This slow-fast-slow pattern recalls the first movement.) Copland saw the third movement as the symphony’s freest, with its constant variation of elemental ideas that are rhapsodic in nature.

In a moment of hair-raising frisson, a held chord in the low strings smooths the transition from the third movement into the fourth as the telltale Fanfare theme floats in, played gently at first by the flutes and joined by clarinets. Muscular-sounding timpani with low strings barge through to usher in the iconic brass statement of the Fanfare, a bold answer to the soft woodwinds, suggesting that the voice of the common man heard in the Fanfare speaks in many tones. Before long, the introduction gives way to the movement’s first larger section, replete with jazzy and Latin-sounding rhythms that overtake the introduction’s staid foundation, propelling different sections of the orchestra into buzzing dialogue. Song-like strains follow in a second large section, though hints of the Fanfare sneak in throughout in preparation for a jarring tutti that marks the start to the movement’s final section. A thrilling cri de coeur brings the symphony to its satisfying conclusion.

Time and again, performers, critics and audiences have described the piece as architectural—Leonard Bernstein even compared it to the Washington Monument or Lincoln Memorial. This may have something to do with the Fanfare quotation, which seems to launch from the ground to scrape the sky. Supporting the symphony’s surface exterior, the composer also developed a well-built structure, in which earlier musical ideas and melodies find their way back into the sonic fold to accumulate a memory bank of familiar scaffolding that orients listeners across the 40-minute work. In his program notes for the work’s premiere, Copland outlined his own perception of its relationship to the long history of the symphony, a genre epitomized by the likes of Beethoven and Mahler (Copland particularly valued the latter as a symphonist). In those notes, he highlighted thematic recall across the whole work and, especially, the finale’s sonata-allegro cycling of ideas. Indeed, Copland admired the long tradition and even harbored a trenchant skepticism of his contemporaries’ and immediate predecessors’ manipulation of the symphony genre, a leeriness that may be one reason for his reticence to make a more significant foray himself. For Copland, Sibelius was too disconnected from nineteenth century conventions, for instance, and Roy Harris’s fourth symphony was mislabeled by its composer. Those views further suggest why Copland keeps certain symphonic conventions in the Third Symphony. Many consider the Third Symphony Copland’s sole “true” symphony—earlier pieces seem to contravene Copland’s own standards for the generic label with the Organ Symphony (1924) resembling a concerto, for instance, and the Dance Symphony (1929) being something of a medley of tunes assembled from the early ballet Grohg (1922–25). But the Third Symphony’s formal architecture is far from a musical equivalent of the prefabricated house as once envisioned by luminary Bauhaus designer Walter Gropius or the early-20th century’s packaged Catalog Home kits from Sears, Roebuck and Co. This is not an out-of-the-box solution that follows to the letter earlier symphonies’ fast-slow-fast-fast movement patterns or common sonata-allegro structures of exposition, development and recapitulation. Rather, Copland took the symphonic blueprint and fashioned his work with bespoke elements, particularly the outsized Fanfare introduction that echoes throughout the finale.

In part due to its idiosyncrasies, critical opinions of the symphony have shifted over time. Writers first assessed its musical integrity as a symphony, later criticized its optimistic tone and eventually historicized it within the moment from which it came. The historicizing perspective often gave credit to Copland where it was due, mindful that he intended to capture the sweeping optimism of the end of World War II. The work’s optimism landed well with audiences at the time of its premiere, but that tone rang hollower and hollower as Cold War pessimism crept in. Critics wondered whether the last movement’s brash triumph too closely resembled what Shostakovich had produced under the watchful eye of Soviet socialist censorship. While a post-war cultural reset was in process in Europe—marked by the allure of objective technological scientism in the arts meant to avoid subjectivities some feared had led inevitably to fascism—Copland chose emotional exuberance. He was later put into a defensive position amid McCarthyist accusations relating to his and his peers’ political views, an ironic twist as he had sought out American governmental service to conduct patriotic work in the years leading to the Third Symphony’s composition. He had even undertaken cultural ambassadorship travel on behalf of the U.S. to South America to meet its brightest composers. Still, the symphony has become a mainstay in the orchestral repertoire and outlived dim midcentury views, a vindication that matches the story that the symphony itself tells.

—Jacques Dupuis