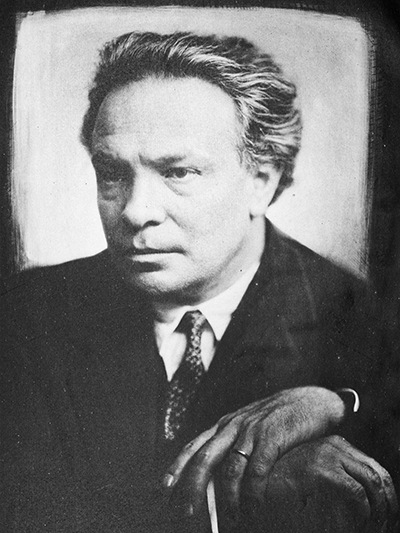

Ottorino Respighi

Born: July 9, 1879, Bologna, Italy

Died: April 18, 1936, Rome, Italy

Pini di Roma ("Pines of Rome")

- Composed: 1924

- Premiere: December 14, 1924, Augusteo Orchestra, Rome, conducted by Bernardino Molinari

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: February 1926, Ottorino Respighi conducting

- Most Recent: April 2015, John Adams conducting

- Recordings: Respighi: The Pines of Rome released in 1946, Eugene Goossens conducting; Respighi: Pines of Rome, Fountains of Rome, Metamorphoseon Modi XII released in 2000, Jesús López Cobos conducting; Classics at the Pops released in 2004, Erich Kunzel conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 6 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, nightingale tape, ratchet, small cymbals, tam-tam, tambour de Basque, triangle, harp, celeste, organ, piano, strings

- Duration: approx. 23 minutes

As Ottorino Respighi’s reputation grew after the success of his Fountains of Rome, he began to travel extensively. He conducted his music on both sides of the Atlantic, and he occasionally performed his own piano solo compositions and accompanied singers as they interpreted his songs. Respighi also envisioned two sequels to Fountains of Rome, continuing his Roman trilogy with showpieces expressing other dimensions of the city in his rich and colorful orchestral writing. Pines of Rome and Roman Festivals became linked to the Fountains of Rome, both in the public mind and in recordings and performances throughout the decades.

Respighi’s Roman pieces also caught the attention of Benito Mussolini when he came to power in 1922, but Respighi remained largely uninvolved with politics. His position at the Liceo Musicale had exempted him from military service when Italy entered the First World War in 1915, and the international fame he accumulated over the following years gave him a level of freedom to take a neutral stance toward the Fascist government. Despite his neutrality, though, Respighi’s popularity encouraged the Fascist regime to exploit his music for their own political purposes. While some might perceive fascist propaganda in the pageantry of Respighi’s Roman trilogy, particularly in Pines of Rome and Roman Festivals, Respighi was motivated simply by his fascination with the timbres of the orchestra and his devotion to using the kaleidoscopic colors to paint images in sound.

As he had done in Fountains of Rome, Respighi composed Pines of Rome in expressive and picturesque orchestral colors that evoke the subject of the music. His musical sequel also takes the form of four continuous movements that guide the audience on a tour through time and space. Each movement illustrates a scene of life and nature surrounding a particular site of the iconic pine trees of Rome. The musical tour moves geographically around the perimeter of Rome, and, like Fountains of Rome, it traces the course of a day fading to night and reaching dawn again. Pines of Rome features another layer of temporality in its evocation of history, stretching from the contemporary city back through early Christianity to the Roman Republic. The piece also suggests a narrative trajectory beginning with children pretending to be soldiers and ending with the footsteps of an army. These layers of picturesque storytelling emerge from the program Respighi created:

- The Pines of the Villa Borghese. Children are playing in the pine grove of Villa Borghese: they dance round in circles, they pretend to be soldiers, marching and fighting, they become intoxicated with their shrieks like sparrows in the evening, and depart in a swarm. Suddenly, the scene changes…

- Pines Near a Catacomb…and behold the shadows of pines circling the entrance of a catacomb: a heartfelt psalmody rises from the depths and fills the air solemnly like a hymn, then mysteriously disperses.

- The Pines of the Janiculum. A quiver runs through the air: the pines of the Janiculum are silhouetted in the clear light of the full moon. A nightingale sings.

- The Pines of the Appian Way. Misty dawn on the Appian Way. The tragic countryside watched over by solitary pines. Indistinct, incessant, the rhythm of innumerable footsteps. The poet has a fantastic vision of ancient glories: the trumpets sound and, in the brilliance of the new sun, a consular army bursts forth toward the Via Sacra, in order to ascend the steps of the Campidoglio in triumph.

Each movement features a meaningful component of sound to create its scene. In the first movement, Respighi quotes a traditional children’s singing game, “Madama Doré,” moving the melody through different instrumental combinations in the orchestra. He also transcribed the cries of children at play to accompany the singing game. The second movement evokes the gloominess of a tomb and the solemn Christianity of the catacombs through quotations of chant, heard prominently in the muted trumpet. In the third movement, muted strings and impressionistic piano ripples set the scene of the moonlit night. The recorded sound of a real nightingale enters through the power of a gramophone, a significant development of music technology. Respighi was the first composer to include a phonograph record alongside the standard orchestral instruments, making his Pines of Rome an innovative and thought-provoking piece. The final movement evokes the footsteps of the soldiers through a low ostinato of piano, timpani and strings.

Pines of Rome premiered in December 1924 at the Augusteo in Rome, the same venue where Fountains of Rome premiered a few years earlier. While the audience had responded to the first performance of Fountains of Rome with ambivalence, the debut of Pines of Rome met with overwhelming success. Another year would pass before the U.S. premiere, which took place when Respighi traveled here for the first time in 1925–26. Arturo Toscanini wanted to conduct the American premiere of Pines of Rome at Carnegie Hall with Respighi in attendance, and so New York audiences heard the piece for the first time on January 14, 1926. This was Toscanini’s first concert as conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and the performance was a great success. The audience was thrilled to have the composer appear before them at the end of the piece. Respighi then traveled to Philadelphia to conduct the piece with Leopold Stokowski’s orchestra, and his tour continued through cities including Washington, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Chicago. The physical presence of the composer in the U.S. generated much excitement for his music, especially for Pines of Rome, and the positive response to the Roman tone poem continues to this day.

—Dr. Rebecca Schreiber