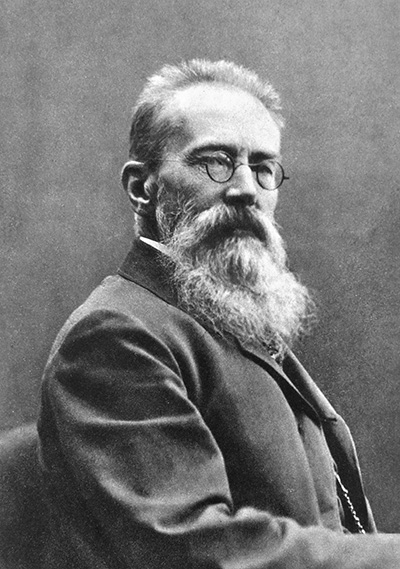

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Born: March 18, 1844, Tikhvin, Russia

Died: June 21, 1908, Lyubensk, Russia

Sheherazade, Op. 35

- Composed: 1888

- Premiere: October 28, 1888, Russian Symphony Concerts, St. Petersburg, Rimsky-Korsakov conducting

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: February 1910, Leopold Stokowski conducting

- Most Recent: May 2015, Louis Langrée conducting

- Recording: Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade (abridged, movements 1 & 3 only) released in 1921, Eugène Ysaÿe conducting

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes (incl. English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, harp, strings

- Duration: approx. 45 minutes

Although he received no formal training in composition, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov is widely considered to be a master of orchestration and an architect of Russian musical style. His interest in music began at a young age with private piano lessons, and, by the age of 10, he had created his first amateur compositions. Shortly afterward, Rimsky-Korsakov entered the Naval College in St. Petersburg, where he developed military values under the guidance of his elder brother, Voin. As he progressed in his naval career, though, Rimsky-Korsakov persisted in fueling his musical development by continuing piano lessons and attending operas in St. Petersburg.

At age 17, Rimsky-Korsakov made the acquaintance of composer Mily Balakirev, who became his music tutor and introduced him to the young composers Modest Mussorgsky and César Cui, as well as the critic Vladimir Stasov. With these introductions, Rimsky-Korsakov joined the ranks of a group of musicians whom Stasov later named the “Mighty Handful” and the “New Russian School.” They became a cohort promoting Russian musical nationalism in the 1860s, seeking to establish a national identity for Russia by foregrounding in their music folk idioms and a conventional Eastern style. They distanced themselves from the established Germanic symphonic tradition, instead composing operas as well as programmatic orchestral music following the progressive example of Franz Liszt and the New German School.

Rimsky-Korsakov embraced the aesthetics of the New Russian School in Sheherazade, his programmatic symphonic suite alluding to the well-known collection of folktales The Arabian Nights, or One Thousand and One Nights. In the story, Sheherazade seeks to become the wife of the brutal Sultan Shahryar, ruler of the Sasanian Empire, with a plan to overcome his cruelty.. On their wedding night, Sheherazade begins to tell him a tale and leaves it unresolved, continuing her storytelling little by little each night. Her tales convey themes of magic, romance and adventure, and her storytelling keeps the Sultan intrigued and, thereby, keeps him from killing her. By the end of the one thousand and one nights of Sheherazade’s tales, the Sultan has undergone a transformation from brutal to merciful and grants Sheherazade her life.

In his autobiography, My Musical Life, Rimsky-Korsakov described his creative process:

“The program I had been guided by in composing Sheherazade consisted of separate, unconnected episodes and pictures from The Arabian Nights, scattered through all four movements of my suite…closely knit by the community of its themes and motives, yet presenting, as it were, a kaleidoscope of fairy-tale images and designs of Oriental character.”

Rimsky-Korsakov evoked the soundworld of The Arabian Nights through the musical style of the New Russian School. The four movements of the suite suggest various scenes of the folktales, and musical themes embodying Sheherazade and the Sultan return throughout the piece to reflect the narrative framework of Sheherazade telling her fantastical tales to the Sultan. However, as Rimsky-Korsakov explained in his autobiography, the themes of Sheherazade and the Sultan transform so that the listener can interpret the themes not just as the characters but as more dynamic elements weaving in and out of the stories.

The Sultan is depicted at the beginning through a loud, low, unison statement in the dark timbres of low brass, clarinet, bassoon, violin and low strings, suggesting the Sultan as a commanding, dominant and imposing figure. Sheherazade’s famous solo violin theme follows shortly thereafter, an expressive, flowing melody accompanied sparsely by harp.

After the violin’s cadenza, the music delves into Sheherazade’s first tale, “The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship.” The beginning section introduces a theme representing Sinbad’s ship, a lilting variation of the Sultan’s theme in the violins over repetitive undulating waves in the low strings. The sea transforms throughout the movement, with a tranquil section followed by the turbulence of energetic woodwinds. The juxtaposed scenes provide the opportunity for the listener to imagine a quest on the seas and to recall Rimsky-Korsakov’s naval career and the inspiration of his own experiences on the sea.

The second movement, “The Legend of Prince Kalendar,” begins with Sheherazade’s narrative theme. Following her introduction, a playful and impulsive bassoon solo suggests the persona of the Prince embarking on an adventure. The third movement introduces a story of romance, “The Young Prince and the Young Princess.” The movement opens with a slow, sweet melody evoking the quality of young noble love. The middle section is more light-hearted, a playful march, perhaps representing their carefree attitudes, before returning to the slower music of the opening of the movement.

The final movement concludes the piece with intensity and color: “The Festival at Baghdad. The Sea. The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock.” The Sultan’s theme begins the movement, followed by a brief response from Sheherazade. Then the music takes off in a frenzy. Thematic material from the previous movements reappears here, with the sea as the most prominent. The music features a break that could indicate the crash of the ship upon the cliff. The piece concludes with the empowerment of Sheherazade: the Sultan’s theme appears in muted tones and Sheherazade’s theme enters an octave higher than it originally appeared in the first movement, suggesting her elevation and triumph over the Sultan.

When Sheherazade premiered in 1888, the performance was almost canceled. Rimsky-Korsakov served as director of the Russian Symphony Concerts in St. Petersburg and planned to present his piece for the first time during that season. However, some members of the Imperial Russian Musical Society felt Sheherazade was too light and playful and might corrupt the aesthetics of the musical youth. Despite their concern of superficiality, they relented, and Sheherazade was allowed to appear on the program to considerable success. Ever since its uncertain premiere, Sheherazade has grown in popularity, gaining renown as a symphonic suite in concert halls around the world and taking on new life in a ballet adaptation, beginning with the Ballets Russes Parisian premiere in 1910. The colorful musical story of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade has made it one of his most famous pieces, transporting its listeners to the world of The Arabian Nights with every performance.

—Dr. Rebecca Schreiber