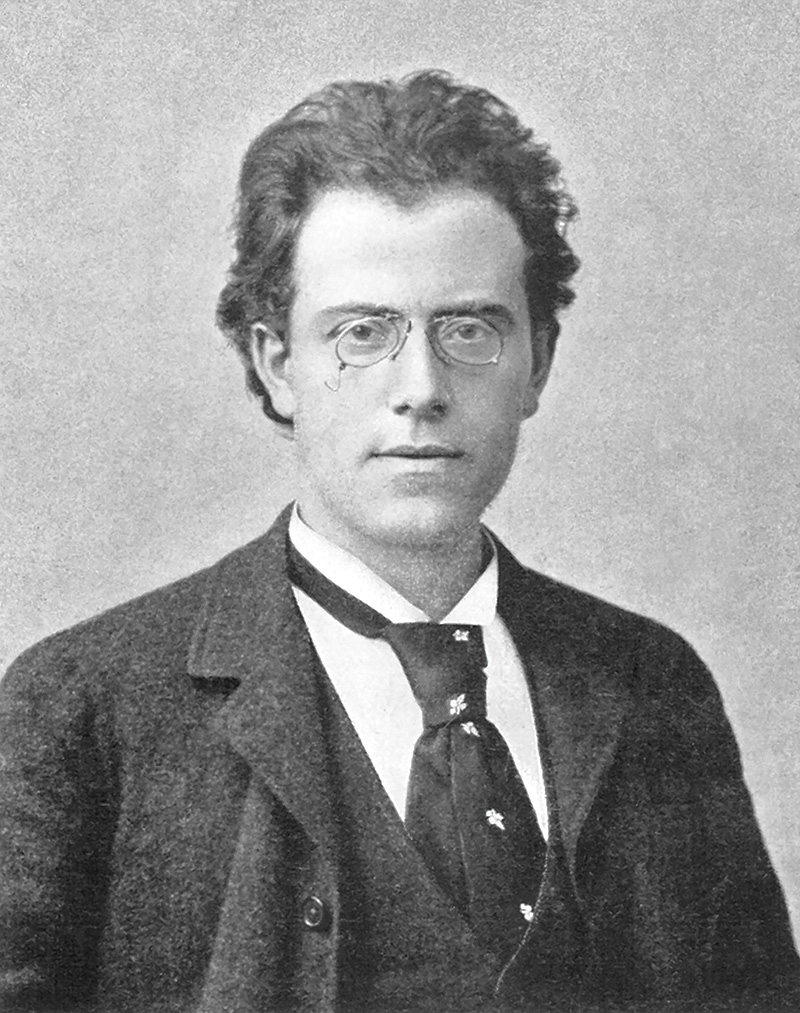

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, Kalischt, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, Vienna, Austria

Symphony No. 6 in A Minor, Tragic

- Composed: 1903–04

- Premiere: May 27, 1906 in Essen, Mahler conducting

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: November 1972, James Levine conducting

- Most Recent: January 2003, Paavo Järvi conducting

- Instrumentation: 4 flutes (incl. 2 piccolos), piccolo, 4 oboes (incl. 2 English horns), English horn, 4 clarinets (incl. E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 4 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 6 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, bells, chimes, cowbells, crash cymbals, hammer, rute, snare drums, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangles, xylophone, two harps, celeste, strings

- Duration: approx. 80 minutes

Perhaps nowhere is the complex, fascinating, slightly disturbing character of Gustav Mahler better seen than in the composition of his Sixth Symphony: perfectionist conductor, obsessive creator; doting father, loving but insensitive husband; universal philosopher, filled with self-doubt—all are reflected in this awesome work that many regard as his greatest symphony for its masterful reconciliation of form and matter.

In 1902, Mahler married Alma Schindler, daughter of the Viennese painter Emil Schindler. Alma was a talented musician, a fellow pupil with Arnold Schoenberg of the teacher Alexander von Zemlinsky, privy to the highest circles of Austrian cultural aristocracy. She was said to be the most beautiful woman in Vienna. Later in the year, their first child, Maria, was born. Little “Putzi,” as they nicknamed her, became the joy of Mahler’s life, and she was one of two things that could get his mind off his work. (Strenuous physical exercise was the other. He was an inveterate swimmer and hiker.) Alma recalled the relationship of father and daughter in her memoirs of her husband. “Each morning our child went into Mahler’s study,” she wrote. “There they talked for a long time. Nobody knows what they said. I never disturbed them. We had a persnickety English girl who always brought the child to the door of the study clean and neat. After a long time Mahler came back, hand-in-hand with the child. Usually she was plastered with jam from head to toe, and my first job was to pacify the English girl. But they both came out so close to each other, and so content with their talk, that I was secretly pleased. She was absolutely his child.”

Mahler loved Alma as well, of course, and often expressed his affection in charming ways, as she recounted: “In the summer of 1903, two movements of the Sixth were finished and the ideas for the remaining movements were completed in his head. Since I was playing a lot of Wagner at that time, Mahler thought of a sweet joke. He composed for me the only love song he ever wrote, "Liebst Du um Schönheit" [‘If you love for beauty, do not love me’], and he put it between the title page and the first page of Die Walküre. Then he waited day after day for me to come across it, but for once I did not open this score at that time. Suddenly he said: ‘Today I fancy having a look at Walküre.’ He opened the book and the song fell out. I was happy beyond words and we played the song that day at least twenty times.”

Yet this same man was just as often completely insensitive to her needs. She had to miss many parties and receptions for lack of the proper evening clothes demanded by Viennese society but which it never occurred to him to provide for her. She had to manage the household around his schedule, desires and ambition. One of the conditions of their marriage was that she give up composing, a discipline in which she had shown a fine talent as a young woman and which was her primary creative outlet. Despite her loving devotion to Mahler and his work, she accumulated a latent anger with him during the years of their marriage. It exploded during his last years, when the Mahlers were living in New York City so he could conduct the New York Philharmonic and Metropolitan Opera, and it came as a painful revelation to him that he had denied her a life of her own. He was so shaken that he agreed to an analysis by none other than Sigmund Freud. The two met in Leyden, Holland, and Mahler regained much of his emotional equilibrium, but he carried a massive guilt with him for the rest of his days. The afternoon that he finally sat at the piano and played the lovely songs Alma had written some 10 years earlier, but which he had refused until then to acknowledge, must have been a time of intense regret.

The summers of 1903 and 1904 spent at the family’s country retreat in the village of Maiernigg on the Wörthersee in Carinthia, when he was working on the Sixth Symphony, were times of apparent happiness for Mahler and his family. Although Alma’s misgivings about their life together were already beginning to fester, the birth of a second girl, on June 15, 1904, gave her a more pressing focus for her thoughts than her own disappointments. Mahler adored his daughters and loved the country, and he seemed contented. He was at the height of his creative powers and work on the new symphony went so well that he even found time to compose some songs. The music he wrote, however, was far removed in mood from the halcyon happiness of Maiernigg. Alma noted in September 1904, “He finished the Sixth Symphony and added three more songs to the two Kindertotenlieder (‘Songs on the Death of Children’) he had composed in 1901. I found this incomprehensible. I can understand setting such frightful words to music if one had no children, or had lost those one had.... What I cannot understand is bewailing the deaths of children who were in the best health and spirits, hardly an hour after having kissed them and fondled them. I exclaimed at the time: ‘For heaven’s sake, don’t tempt Providence!’” Of the Sixth Symphony, she said, “In the third movement, he represented the a-rhythmic games of the two little children, tottering in zigzags over the sand. Ominously, the childish voices become more and more tragic, and at the end die out in a whimper. In the last movement he described himself or, as he later said, his hero: ‘It is the hero, on whom fall "three blows of Fate," the last of which fells him like a tree.’ Those were his words.” Mahler’s explanation for writing such music? “I don’t choose what to compose. It chooses me,” he said, fatalistically.

The visions of terror and death that Mahler created on a beautiful Austrian summer’s day were more than simply upsetting—they were prophetic. The finale’s “three blows of Fate,” portrayed by a shattering cry from the full orchestra and the strongest possible stroke from a hammer (usually played on the bass drum), befell Mahler in 1907. Early in the year, a serious heart ailment was discovered; on June 15, his darling “Putzi,” not yet five years old, died; one month later, he was forced from his directorship of the Vienna Opera by criticism and the city’s subtle but powerful anti-Semitism. In her preface to Mahler’s letters, Alma commented, “He said so often: All my works are an anticipando of the life to come.”

■ ■ ■

Just before the short score of the Symphony was completed in September 1904, Mahler wrote to his biographer Richard Specht, “My Sixth will present riddles to the solution of which only a generation will dare apply itself which has previously absorbed and digested my first five symphonies.” Since Mahler himself shied away from clarifying the message of the “three blows of Fate” in the finale for the work’s premiere, it was only to be expected that this work was the one of his symphonies that took longest to find public acceptance. It did not achieve wide favor when it was first heard in May 1906 (Mahler was deeply wounded by Richard Strauss’ criticism of its “excessively noisy orchestration”), nor when it was played later that season in Munich, Vienna, Leipzig and Dresden. It seems not to have been performed anywhere between 1907 and Mahler’s death four years later. The judgment of Oskar Fried, one of the composer’s most important disciples, was called into question by the critics when he conducted the Sixth Symphony in successive seasons in Vienna in 1919 and 1920. The work was not heard in America until 1947, the last of his completed symphonies to reach this country. Yet Hans Redlich wrote in a 1920 article that this work was “Mahler’s essential heritage for the future.” The “Second Viennese School” immediately adopted the piece. Alban Berg wrote to Anton Webern that it is “the one and only Sixth—despite the ‘Pastoral’ [of Beethoven].” Berg admitted that the symphony’s finale was the starting point for the last of his Three Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6 of 1914. Arnold Schoenberg wrote essays in 1913 and 1934 admiringly analyzing the structural subtleties and melodic construction of the Andante. It has only been since the 1960s, when recordings first opened to the world the breathtaking scope of Mahler’s achievement, that the Sixth Symphony has taken its proper place as one of his best—some say his greatest—works.

■ ■ ■

The Sixth Symphony’s first movement is in sonata form. A short, five-measure preface establishes the A minor tonality and the violent, martial nature that dominates much of the movement. The wide leap of an octave characterizes the main theme, presented by the strings. As a transition to the contrasting theme, the timpani pound out a heavy motive Mahler designated as the “rhythm of catastrophe.” Above these ominous strokes, he placed another of his musical codes for Fate, a loud major triad slipping into a soft minor one, here intoned by the trumpets. Placed against these stern musical thoughts is the sweeping second theme, in which, Mahler told Alma, he tried to capture her youthful, exuberant personality. The exposition, as in the Classical model, is directed to be repeated. The development, begun with the timpani strokes, is an extended working-out of the earlier themes into which is introduced another of Mahler’s musical symbols—the hollow-sounding tintinnabulation of cowbells. This effect, “the last earthly sounds heard from the valley below by the spirit departing from the mountain top,” explained the composer, was meant to represent the most remote loneliness. It occurs again in the Seventh Symphony. The recapitulation returns the martial main theme and Alma’s sweeping melody, and from them grows an extended coda that achieves a certain belligerent affirmation in its closing pages.

Hans Redlich wrote that the “chief characteristic of the Scherzo is its sinister artificiality.” In place of the cheerful dance of the traditional scherzo is a brutal essay in steely A minor that is mocking and derisive in spirit, and even parodies fragments of the opening movement’s themes to build its own melodic material. The more lightly scored trio, spun from motives stated in the Scherzo’s opening pages, is marked Altväterisch—“in an antiquated manner.” These are the mixed-meter strains that Alma believed represented her children’s clumsy games, and that so frightened her in their eventual disintegration as the movement concludes.

The slow third movement, in the harmonically distant key of E-flat major, is akin in mood to the somber introspection of the Kindertotenlieder. Its only clear musical connection with the rest of the work is the symbolic use of cowbells, and, taken by itself, it seems a lovely, if somewhat hyper-emotional display of post-Romantic sensibility. In its larger aspect, however, as an integral part of the symphony’s structure, it becomes a foil to the surrounding menace, an almost painfully beautiful interlude—a pale child’s wan smile amid the rubble. Formally, it is built around three returns of the legato main theme separated by episodes that are, by turns, pastoral, mysterious and passionate.

In 1921, the distinguished scholar Paul Bekker wrote of this work, “All the essentials of the symphonic action are entrusted to the finale more decisively than ever.” This magnificent closing movement, almost a half-hour in length, culminates the vision that inspired the work. The form is a large sonata structure of enormous complexity, but the emotional thrust of the music is organized around the “three blows of Fate” and the bleak concluding dirge in the low brass. Long developmental lines, perhaps representing rising hope and confidence, are cut short by the sinister strokes. (Although Mahler called them “hammer-strokes” in the score, he instructed that the timbre must be “short, powerful, but dull in sound...not of metallic character,” so the part is usually played on bass drum.) The third and final stroke, which is followed by the timpani’s “rhythm of catastrophe” from the first movement and the major-minor chord shift, leads directly to the coda, a solemn threnody murmured in sepulchral tones by the trombones and tuba. A single, final cry from the full orchestra above the faltering heartbeat of the timpani’s motive ends the symphony.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda