by Hannah Edgar

Director of Choruses Matthew Swanson conducts the May Festival Chamber Choir during a performance at Westwood First Presbyterian Church, October 2024. Credit: Charlie Balcom

Matthew Swanson, 35, has been a fixture of the May Festival Chorus since 2012, when he joined the ensemble as a tenor. In the intervening years, he’s worked for the organization at multiple levels: in the box office for two years, as a Festival Conducting Fellow in 2015, and as Associate Director of Choruses, leading the Festival’s special projects and conducting the May Festival Youth Chorus.

All that experience flows easily into the concerts Swanson is preparing this fall. Chichester Psalms, with Marin Alsop? He’s already an old hand at all things Leonard Bernstein, having been instrumental in the Festival’s performances of MASS (2018) and Candide (2022). Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, with Richard Egarr? Although the May Festival hasn’t programmed the Oratorio in more than a century, Matthew has sung it at Knox Church in Cincinnati and knows Egarr from his grad school days in Cambridge, England to boot.

The seeds for such rich experiences need to take root somewhere. For Swanson, it was rural southeast Iowa. His family runs a farm with corn, soybean and alfalfa fields and a herd of about 80 Sim-Angus cattle. The nearest incorporated town, Ollie, has a population of 200.

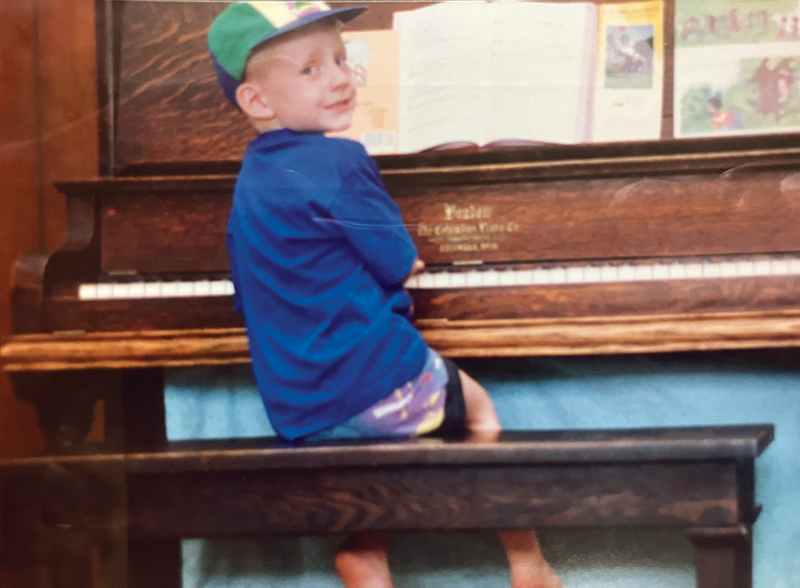

At an early age, Swanson began his journey into music by taking piano lessons from Kay Evans, who also taught elementary music and led the choir at the high school.

Matthew Swanson at age 4, playing the piano at home.

Both his parents played instruments in their youth, and his mother sang in the church choir before he was born. Swanson followed in her footsteps in their church’s youth program, where an attentive instructor noticed Swanson’s zeal for singing. She recommended that Swanson audition for the Greater Ottumwa Vocal Arts Project, or GOVAP, a regional choir serving kids from fifth through seventh grades.

Swanson at age 10, as a new member of the GOVAP Children’s Choir.

The program was “transformative,” says Swanson. He experienced all his first choral milestones through GOVAP: his first time singing in parts, his first time singing a non-English language and his first time singing with an orchestra. He also encountered core repertoire, even if he didn’t understand what that meant at the time.

“I remember working on Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel with an orchestra, and the conductor said, at some point, ‘You know, you’re going to sing and hear these songs for the rest of your life.’ I thought, ‘What? How is that possible?’

“He was absolutely correct. I learned ‘The Vagabond,’ ‘The Roadside Fire,’ and all these other great songs from that cycle when I was 10. And sure enough, they have followed me around my whole life.”

In parallel with his years in GOVAP, Swanson had been introduced to the trumpet through his school music program and excelled at that, too. When he enrolled at Notre Dame for college, he declared a trumpet performance major and assumed his singing days were over.

Swanson at age 17, after playing in the Iowa All-State Band.

Fate had other plans. Turns out the director of Notre Dame’s symphony orchestra, Daniel Stowe, also directed its Glee Club. After he learned that Swanson sang, too, Stowe staged an “intervention, or invitation”—per Swanson—for him to join that ensemble, too. The Glee Club embarked on a 10-day Southeast tour shortly after Swanson joined.

It wasn’t Swanson’s first concert tour. Nonetheless, that experience became “the best week of [his] life” thus far.

“I thought we were singing such interesting repertoire: Gregorian chant, Renaissance motets, barbershop and close harmony songs, folk songs and weighty Romantic works. It was almost everything that you could pack into a concert,” Swanson remembers. “Taking a band on tour, it’s almost more stuff than people. There was something magical about the fact that the singers themselves were the instruments…. Singing is a sonic act, a physical act, an emotional, communal and spiritual act all at the same time.”

When the time came for him to apply to grad school, Swanson was at another crossroads: Should he apply to programs in trumpet performance or pursue his interest in choral conducting? He opted for the latter, which brought him to the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (CCM)—and, by extension, to the May Festival Chorus. He’d encountered the choral–orchestral repertoire occasionally at Notre Dame, and the May Festival offered an opportunity to delve deeper.

Matthew Swanson and Daniel Stowe, conductor of the University of Notre Dame Glee Club and Symphony Orchestra, following the Glee Club’s 2011 Commencement Concert.

“When I saw the list of repertoire they were doing all in one season”—Carmina Burana, the Duruflé Requiem, the Stabat Mater and Te Deum of Verdi, Russian opera choruses, Poulenc’s Gloria, and the Brahms Requiem—“I thought, ‘Oh, I’ve just got to get down there,’” Swanson recalls.

Thanks to his experience in the May Festival, by now Swanson has sung most of the choral–orchestral biggies—essential to him now as a director, “because I can have some sympathy for what the singers might be going through.” He also got to observe Director of Choruses Robert Porco’s leadership, which left a deep impression.

“That was a huge education for me, to [work with] someone of such vast experience and high standards of excellence. He has a deep commitment to the art and ideals of volunteer singing and what that can mean for a community of people,” Swanson says.

But Swanson’s education wasn’t yet complete. Between his degrees at CCM, he applied to a master’s degree program in choral studies at the University of Cambridge, somewhat on a whim. To his surprise, he got in—and to his delight, his application to King’s College, home to the prestigious choir of the same name, was also accepted. When he wasn’t busy singing around the university, he got to sit in on the group’s rehearsals.

In the end, Swanson’s biggest takeaway from that experience wasn’t technical or musical. Nor was it leadership skills, per se. Instead, it was witnessing, in live-time, that even the world’s most prestigious choirs never rest on their laurels.

“I think it’s easy to look at any institution that’s achieving at a high level and take it for granted. But any institution which is achieving—by whatever definition of success you wish to apply—is doing so not because of one instance of hard work and effort, but consistent instances of hard work and effort over long, long spans of time,” he says. “None of that happens in a vacuum; none of it happens automatically. It’s the process of truly daily work.”

Director of Choruses Matthew Swanson conducts the May Festival Chamber Choir during a performance at Westwood First Presbyterian Church, October 2024. Credit: Charlie Balcom

The same could be said of his path toward helming the May Festival Chorus. Swanson didn’t just work for the organization at every level: As director of the May Festival Youth Chorus, he inaugurated an annual commissioning project for the ensemble, which gave choristers the experience—many for the first time—of performing a piece from scratch. The roster of commissioned composers has been impressive, too. Brazilian-American composer Clarice Assad kicked off the program in 2019 with Cantos da Terra, a “charming, inventive and jazz-inflected” riff on Brazilian Christmas songs. Eminences like Gwyneth Walker and James Lee III have followed. To celebrate the 150th anniversary, the Youth Chorus joined the May Festival Chorus for the world premieres of James MacMillan’s Timotheus, Bacchus and Cecilia, which went on to be performed at this year’s BBC Proms, and James Lee III’s Breaths of Universal Longings, which included texts inspired by members of the Youth Chorus.

“I think it’s important that people are writing for young voices and that our students have the opportunity to understand what it means to be a composer and what a commission is…. In many cases, we were able to bring the composer here for them to meet,” Swanson says.

Young performers clearly stand to learn a lot from experienced composers. But what about young composers? They stand to learn a lot by working with performers, too—and they rarely get the chance to do so before heading off to college. So, Swanson also steered last year’s “25 for 25: A New Time for Choral Music,” the May Festival’s massive commissioning process undertaken in partnership with the New York-based Luna Composition Lab and 25 community ensembles. The initiative matched local choirs with talented teenage composers who would write a new work for them. In the process, the tide raised all ships: The choirs got to premiere a work specially made for them, and the young Luna Lab composers—all of whom are girls or nonbinary—would get a valuable professional clip they could present to college composition programs.

25 for 25 augmented the work started by former May Festival principal conductor Juanjo Mena, who established the May Festival Community Chorus, a non-auditioned ensemble drawn from other Cincinnati-area choruses. In 2018, the year of its inception, Swanson became its de facto chorus manager. Swanson sees promoting “the breadth and the depth of the choral ecosystem in Cincinnati” as a core part of the May Festival’s mission.

Matthew Swanson leads a May Festival Youth Chorus rehearsal in April 2022 at the Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption.

“The May Festival, throughout its history, has been a celebration of singing in the city and across the region,” Swanson says.

Suffice to say, Swanson is already spinning lots of plates. But, every once in a while, when he has the time, Swanson still busts out his trumpet, mostly to check on his chops. Otherwise, in his spare time, he jokes that he’s “trying very hard to be a tenor,” though he’ll take singing in a choir over singing a solo any day. He hasn’t found anything that beats that feeling.

“I used to talk to the May Festival Youth Chorus about the idea of magic. I think, for me, the best evidence of magic in the world is when a choir starts to sing really, really well in tune and, all of a sudden, these overtones are happening—these notes that no one is singing, but that are produced tangibly and sonically in the world by the combination of us as a whole.

“That’s the closest thing to magic I know.”