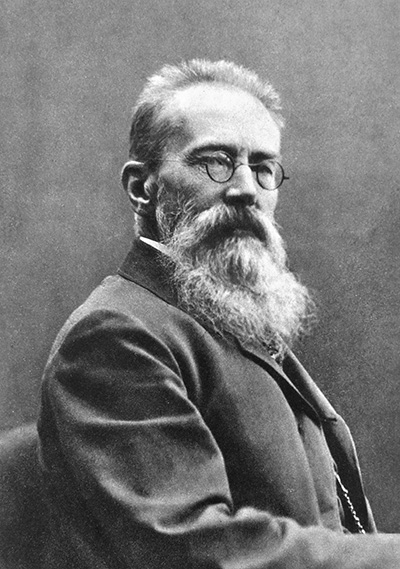

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Born: March 18, 1844, Tikhvin, near Novgorod, Russia

Died: June 21, 1908 in St. Petersburg, Russia

Capriccio espagnol, Op. 34

- Composed: 1887

- Premiere: October 31, 1887 in St. Petersburg, conducted by the composer

- Duration: approx. 15 minutes

Rimsky-Korsakov visited Spain only once: while on a training cruise around the world as a naval cadet, he spent three days in the Mediterranean port of Cádiz in December 1864. The sun and sweet scents of Iberia left a lasting impression on him, however, just as they had on the earlier Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, who was inspired to compose the Jota aragonesa and A Night in Madrid on Spanish themes. Both of those colorful works by his Russian predecessor were strong influences on Rimsky-Korsakov when he came to compose his own Spanish piece in 1887.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s principal project during the summer of 1887 was the orchestration of the opera Prince Igor by his compatriot Alexander Borodin, who had died the preceding winter. Rimsky-Korsakov installed himself at Nikolskoe on the shore of Lake Nelai in a rented villa, and made good progress with the opera, one of many completions and revisions he undertook of the music of his fellow Russian composers. Things went well enough that he felt able to interrupt this project for several weeks to work on a composition of his own, a piece on Spanish themes that was originally intended for solo violin and orchestra but which he re-cast for full orchestra as the brilliant Capriccio espagnol.

He took the new score home with him to St. Petersburg that fall to prepare its premiere with the Russian Concert Society for October. In his autobiography, he recounted the events surrounding the first performance of the work: “At the rehearsal, the first movement had hardly been finished when the whole orchestra began to applaud. Similar applause followed all the other parts whenever the pauses permitted. I asked the orchestra for the privilege of dedicating the composition to them. General delight was the answer. The Capriccio went without difficulties and sounded brilliant. At the concert itself, it was played with a perfection and enthusiasm the like of which it never possessed subsequently, even when led by [the distinguished conductor Arthur] Nikisch himself [later music director of the Boston, Berlin, Leipzig and Budapest orchestras]. Despite its length, the audience insistently called for an encore.” The composer made good on his promise to dedicate the work to the Russian Musical Society Orchestra, inscribing the names of all 67 players on the score’s title page.

The Capriccio Espagnol comprises five brief, attached movements. It opens with a rousing Alborada or “morning-song,” marked vivo e strepitoso — “lively and noisy.” The solo violin figures prominently here and throughout the work, a virtuosic reminder of the origin of the Capriccio as concerted piece for that instrument. A tiny set of variations on a languid theme presented by the horns follows. The Alborada returns in new instrumental coloring that features a sparkling solo for the clarinet. The fourth movement, Scena e canto gitano (“Scene and Gypsy Song”), begins with a string of cadenzas: horns and trumpets, violin, flute, clarinet and harp. The swaying Gypsy Song gathers up the instruments of the orchestra to build to a dazzling climax leading without pause to the finale, Fandango asturiano. The trombones present the theme of this section, based on the rhythm of a traditional dance of Andalusia. The final pages of the Capriccio recall the Alborada theme to bring this brilliant orchestral showpiece to an exhilarating close.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda