PIANO TRIO NO. 3, IN C MINOR, OP. 101

Johannes Brahms

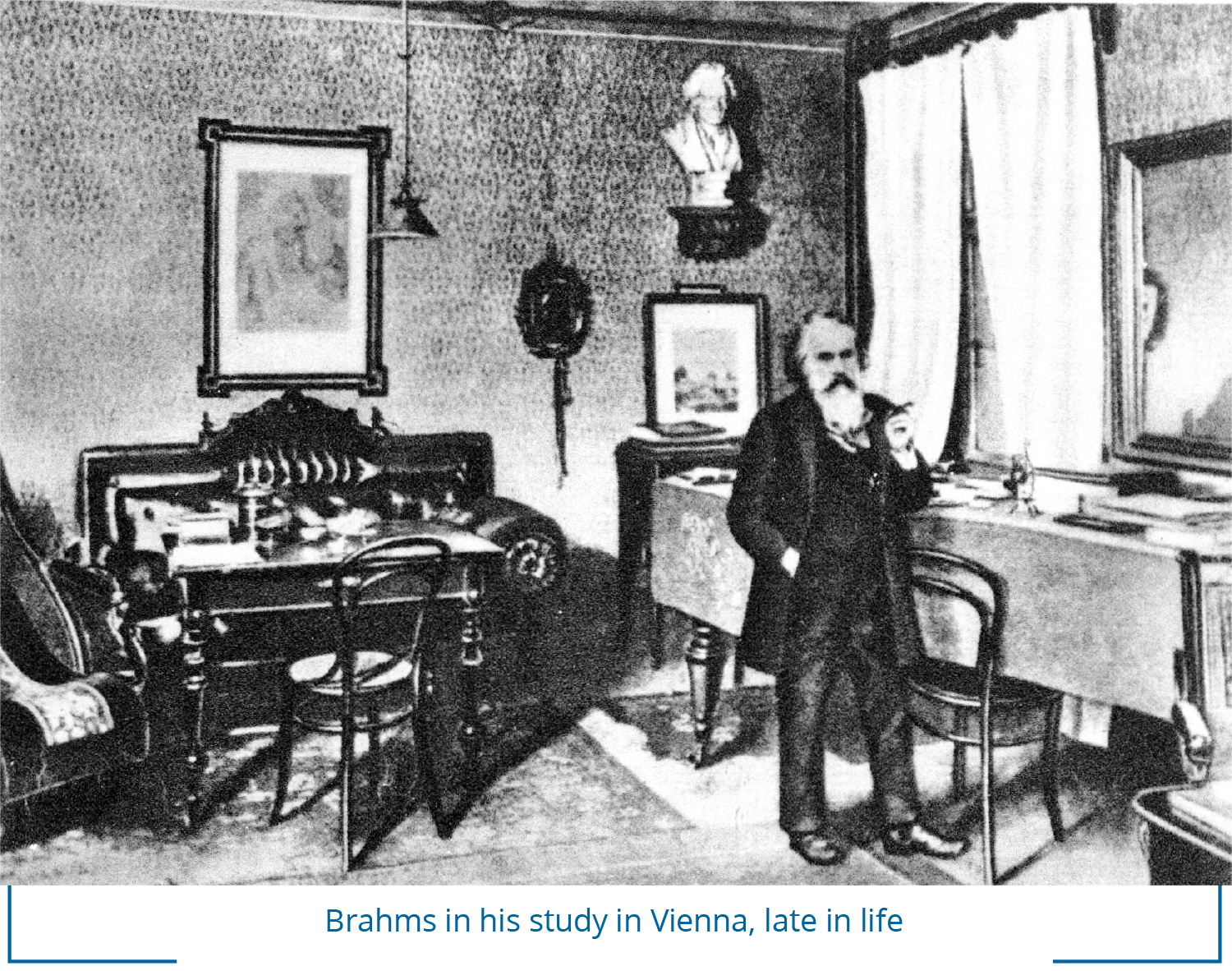

(b. Hamburg, Germany, May 7, 1833; d. Vienna, Austria, April 3, 1897)

Composed 1886; 21 minutes

In 1887, when Clara Wieck Schumann played through the newly published C minor Trio, the third of Brahms’s three piano trios, written when he was 53, she found it “wonderfully gripping . . . No previous work of Johannes has so completely carried me away,” she wrote in her diary. “What a work it is, inspired throughout in its passion, its power of thought, its gracefulness, its poetry.” Brahms had completed the trio in the Swiss resort town of Hofstetten, near Lake Thun, during an extraordinarily productive three-month stay the previous summer. During his time there, he also completed the F major Cello Sonata, Op. 99, the A major Violin Sonata, Op. 100, much of the subsequent D minor Violin Sonata, Op. 108, together with a number of songs. He was at the peak of his creativity.

In 1887, when Clara Wieck Schumann played through the newly published C minor Trio, the third of Brahms’s three piano trios, written when he was 53, she found it “wonderfully gripping . . . No previous work of Johannes has so completely carried me away,” she wrote in her diary. “What a work it is, inspired throughout in its passion, its power of thought, its gracefulness, its poetry.” Brahms had completed the trio in the Swiss resort town of Hofstetten, near Lake Thun, during an extraordinarily productive three-month stay the previous summer. During his time there, he also completed the F major Cello Sonata, Op. 99, the A major Violin Sonata, Op. 100, much of the subsequent D minor Violin Sonata, Op. 108, together with a number of songs. He was at the peak of his creativity.

The opening movement of the C minor trio is one of Brahms’s most intense sonata form movements; even his normally mellow second theme is here ardent and forward-driving in a way that offers little release in the tension. The movement, in common with much of his later chamber music, is also one of his tautest structures and, as in the Second Piano Trio, Brahms omits the traditional repeat of its first section (the exposition). “Laconic” is how his close friend and frequent correspondent Elisabet von Herzogenberg described the movement. “Smaller men,” she wrote, “will hardly trust themselves to proceed so laconically without forfeiting some of what they want to say.”

The scherzo is understated, almost aphoristic, inhabiting a shadowy world of allusion and half-lights. The strings are muted throughout, and the music rarely rises above a piano. “I am happier tonight than I have been for a long time,” Clara Schumann wrote after hearing this movement. The slow movement is a brief, wistful dialogue between the two strings and the piano, with the three instruments only infrequently playing together. Originally drafted with a 7/4 time-signature, the music effortlessly slips from two to three beats to the bar and the textures of the unaccompanied string duo again offer a preview of the Double Concerto, the work Brahms was to compose the following year. The determined finale, with its unpredictable cross-rhythms, remains shrouded in the minor key until sunlight warms the coda to a triumphant conclusion.