Dido, Queen of Carthage, was a remarkable woman. Unlike many heroines in the pantheon of Greek and Roman mythology, her beginnings were not rooted in aether. Nor was she merely a figment of the classical imagination. A historical figure who became myth, Dido has shifted shape and agendas through the ages. She has been transmogrified from lived personage to fictional character by Virgil in The Aeneid; by playwrights Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Nashe in the play, Dido, Queen of Carthage; and by Henry Purcell and Nahum Tate in their opera, Dido and Aeneas, from which this evening’s “Lament” is excerpted; as well as by writers from Ovid to Dante, from Petrarch to Chaucer and beyond.

Dido, Queen of Carthage, was a remarkable woman. Unlike many heroines in the pantheon of Greek and Roman mythology, her beginnings were not rooted in aether. Nor was she merely a figment of the classical imagination. A historical figure who became myth, Dido has shifted shape and agendas through the ages. She has been transmogrified from lived personage to fictional character by Virgil in The Aeneid; by playwrights Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Nashe in the play, Dido, Queen of Carthage; and by Henry Purcell and Nahum Tate in their opera, Dido and Aeneas, from which this evening’s “Lament” is excerpted; as well as by writers from Ovid to Dante, from Petrarch to Chaucer and beyond.

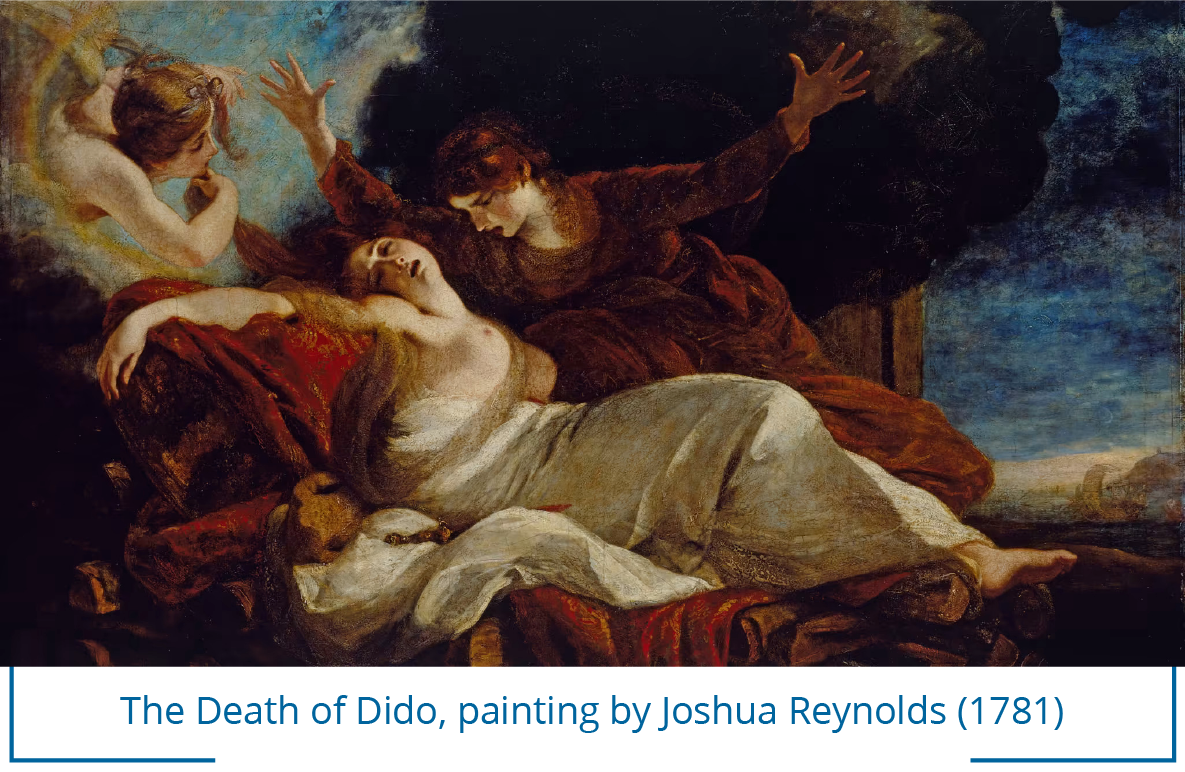

The real Dido, whose name evokes meanings encompassing “beloved” and “the wanderer,” was most likely a Phoenician queen of the city-state of Tyre, which is now S˙ur, in Lebanon. After Dido’s brother murdered her husband, she fled to what is currently Tunisia, where the Berber king Iarbas offered her as much land as could be encircled by an ox hide. Dido cut the hide into strips, exponentially expanding the perimeter of her new kingdom, which would become Carthage, the prosperous city-state she founded. The “Dido Problem” in mathematics—the oldest problem in the Calculus of Variations—takes its name from Dido’s innovative thinking. King Iarbas’s offering did not come without strings attached. To avoid having to marry him, Dido built a funeral pyre and committed suicide, a practice not uncommon during the Greco-Roman era. In Dido’s clear-sighted hands, the gesture took the form of political protest.

When Melinda Wagner and I first spoke about writing a contemporary Dido for Dawn Upshaw and the Brentano String Quartet, we knew immediately that our Dido would not partake of the depiction of women imprinted on us by men through the centuries. We knew, too, that Dido’s epic love for Aeneas and her self-immolation in response to what she perceived as his abandonment of her—romantic tropes devised by Virgil and immortalized by Purcell and Tate (for Aeneas post-dated Dido by anywhere between 50 and 400 years)—needed to metamorphose in our hands. We were compelled by the notion of an epic love in contemporary times. What form might that take for a powerfully strong, complex woman of today, who has long realized her full potential in terms of both career and family? A woman whose experience of first love is but a distant memory. How does she allow herself to get so knocked off kilter, so swept off her feet? What is the fallout of that? In both Virgil and Purcell/Tate’s versions, Dido’s lovesickness is incited and meddled with by Venus and Juno. But in an era without any gods, where does that intensity of feeling come from? It seemed to us that there was no better medium than music with which to explore this question.

Dido of ancient times, whether real or fictional, had no choice. Our Dido, however, has the power to determine her own fate. I have been lucky enough to keep returning, over the years, to a writing retreat on an island where there are no cars, no shops, only a few house, and a landscape strewn with ancient rocks, covered with windblown trees, and ringed by sea. Our Dido’s refuge was inspired by my time in this place. Our Dido does not choose death. She removes herself from the everyday world, she chooses solitude. She returns to nature, she becomes one with it.

Together, Melinda and I have attempted to make something between a song cycle and a monodrama. A piece of music drama that is simultaneously journey and meditation. A reflection on the power of love, on the passage of time, on loss, resilience, and the restorative power of a disappearing world.

—Note by Stephanie Fleischmann