PIANO SONATA IN C MINOR, D. 958, OP. POSTH.

Franz Schubert

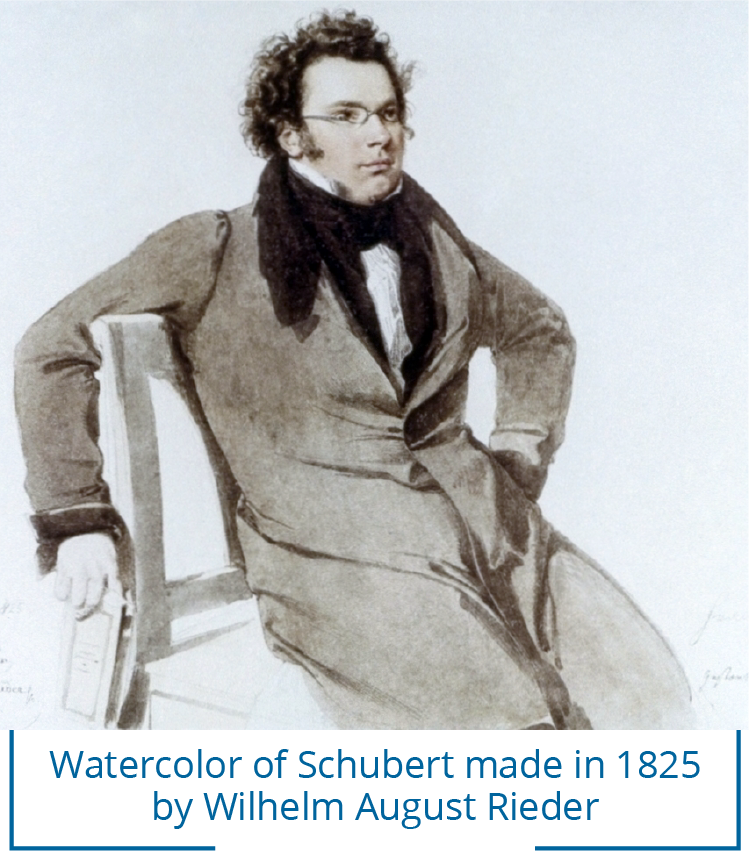

(b. Vienna, Austria, January 31, 1797; d. Vienna, November 19, 1828)

Composed 1828; 29 minutes

Franz Schubert composed three towering piano sonatas in 1828, the last year of his life. They were only published eleven years later and are therefore given the rather ominous looking opus posthumous designation. They progress from

the tragic and brooding C minor (D. 958) to the emotionally wide-ranging A major (D. 959) and to the meditative and peaceful B-flat (D. 960). Schubert worked on all three at the same time, sketching, revising, composing hurriedly in ink

on different sizes of manuscript paper, clearly in a feverish state of mental exhilaration. This final trilogy of sonatas is one of the most striking accomplishments in the entire

piano repertoire.

What drove Schubert in this intensely creative and innovative period? Performers and publishers were ignoring his music. His health was in decline and syphilis had caused all his hair to fall out. His circle of friends was growing smaller. Being unskilled in business matters, his financial position had become desperate. For the final three months of his life, he moved into the Viennese residence of his brother Ferdinand, at Kettenbrückengasse 6. In this apartment, with its piano standing in a corner then, as it does to this day, Schubert wrote these magnificent piano sonatas, evidently knowing that death was not far away. Beethoven had died one year earlier, in the same city; Schubert had been a pallbearer at his funeral. Unlike Brahms, Schubert was not inhibited by Beethoven’s legacy. He was able to take inspiration from Beethoven’s rhetoric and from his dialectic way of composing, replacing Beethoven’s affirmative statements with more open-ended questioning and contradictions.

The opening of the C minor sonata, D. 958, right away recalls the music of Beethoven, specifically his 32 Variations in C minor. But where Beethoven constructs taut, complex musical architecture with clearly defined structures, Schubert is quite independent. He strives after the unattainable and frequently takes us on a path where time, in its normal sense, is suspended. The slow movement, the only real Adagio among Schubert’s mature sonatas, encapsulates the contrast between the mystery of a noble theme – which constantly strives to modulate into ever distant keys and to lose itself in terms of real time and place – and the grim reality of agonized, repeated chords, which force us back to reality. In the short subdued, even melancholy Menuetto, Schubert avoids obvious symmetry, and a restless, rather elusive feeling is created, particularly when the flow is held up by short pauses. The restlessness reaches fever point in the galloping, tarantella-like finale where Schubert explores extremes of modulation and extremes of the keyboard to such a degree that it can, at times, seem as though four hands are playing.