RHAPSODY IN BLUE (1924)

George Gershwin

(b. Brooklyn, NY, September 26, 1898; d. Hollywood, CA, July 11, 1937)

Composed 1924; 17 minutes; arr. Matt Catingub

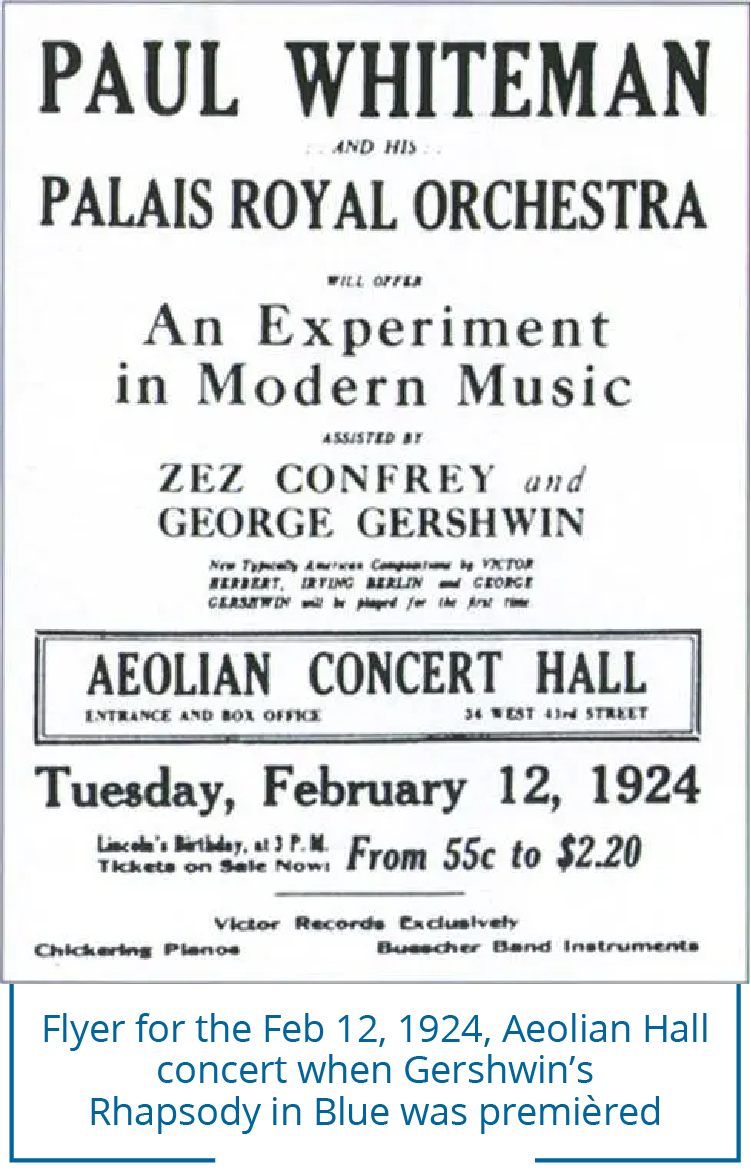

“Whiteman Judges Named,” ran the headline of a short article in the January 1924, edition of the New-York Tribune. “Committee will decide ‘What is American Music.’” Jazz dance band leader Paul Whiteman was in the process of attracting leading lights to his upcoming concert titled “Experiment in Modern Music,” designed with the principal goal of showcasing his virtuoso band in popular songs and dances of the time – and in reaffirming his self-proclaimed role as the ’King of Jazz.’ Rachmaninoff, Heifetz and Zimbalist, three prestigious Russian-born musicians, and Romanian-born soprano Alma Gluck had a big task on their hands in deciding the nature of American music. A no less imposing task lay in the hands of an American-born composer, whose name is mentioned at the bottom of the article: “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto,” it states, though Gershwin, himself, was not aware of the fact. Since it was doubtless a publicity ploy, the jury never publicly delivered its verdict. Gershwin’s ’jazz concerto,’ item 22 in a program of 23 pieces, effectively did that for them.

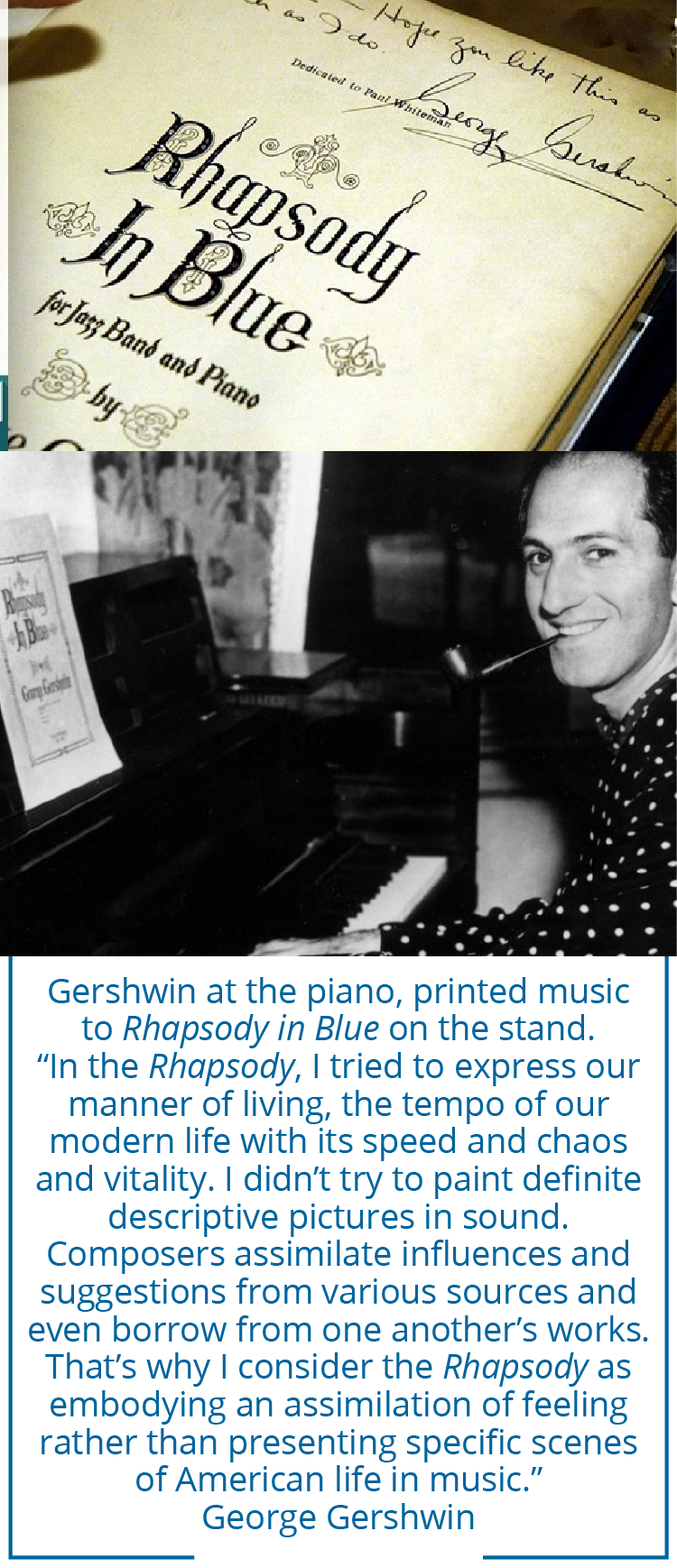

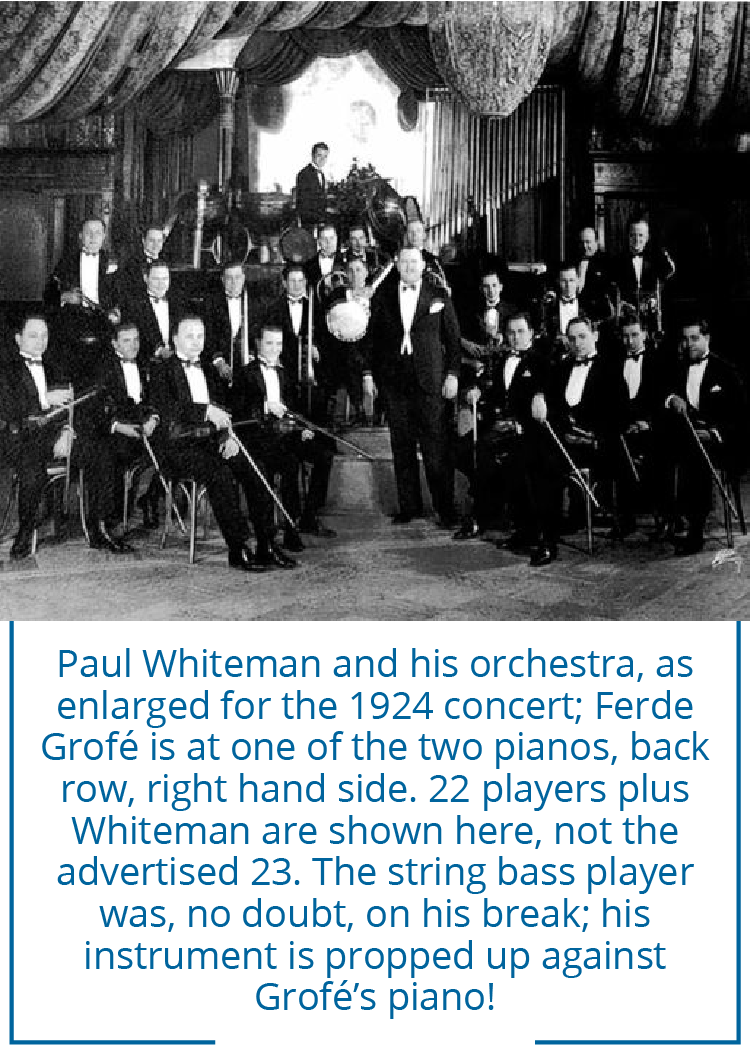

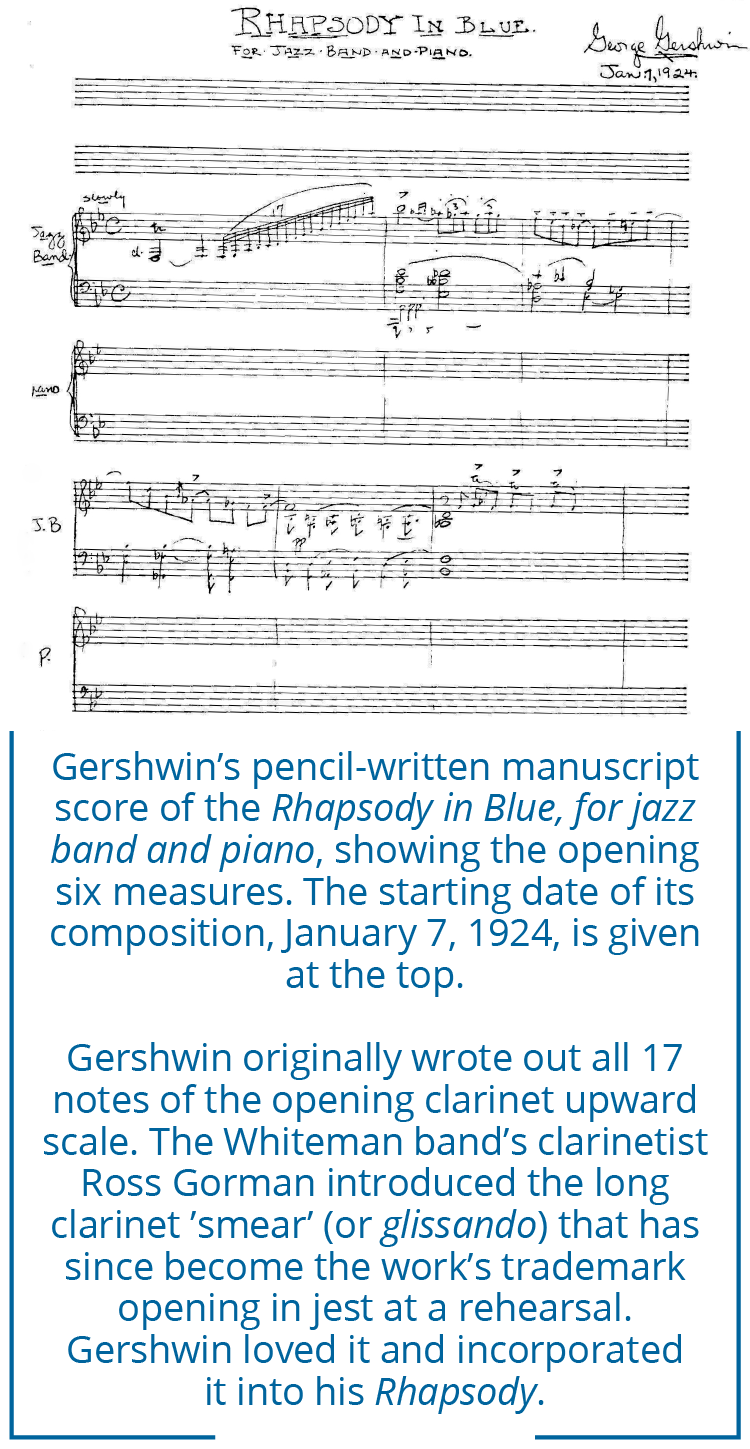

By January 7, 1924, working in the 110th Street apartment he shared with his parents, brothers and sister, George Gershwin began to compose a piece he originally titled American Rhapsody. With his show Sweet Little Devil in its final rehearsals for a run on Broadway, the already seasoned 25-year-old songwriter had to work quickly. His brother Ira came up with the title Rhapsody in Blue, which Gershwin enthusiastically adopted. He worked in pencil rather than ink, to save time, writing in short score, in places leaving his own solo piano lines blank, to be worked out later. The other two staves provided an outline of themes and some instrumentation for Whiteman’s pianist and house orchestrator, Ferde Grofé. “I called there daily for more pages of George’s masterpiece,” Grofé later recalled. Grofé had the advantage of knowing the idiosyncrasies of the leading players of a band he himself played in. He also had more time and vastly more experience to finesse the orchestrations than the unusually busy young songwriter, with an important show opening in New York on January 21.

By January 7, 1924, working in the 110th Street apartment he shared with his parents, brothers and sister, George Gershwin began to compose a piece he originally titled American Rhapsody. With his show Sweet Little Devil in its final rehearsals for a run on Broadway, the already seasoned 25-year-old songwriter had to work quickly. His brother Ira came up with the title Rhapsody in Blue, which Gershwin enthusiastically adopted. He worked in pencil rather than ink, to save time, writing in short score, in places leaving his own solo piano lines blank, to be worked out later. The other two staves provided an outline of themes and some instrumentation for Whiteman’s pianist and house orchestrator, Ferde Grofé. “I called there daily for more pages of George’s masterpiece,” Grofé later recalled. Grofé had the advantage of knowing the idiosyncrasies of the leading players of a band he himself played in. He also had more time and vastly more experience to finesse the orchestrations than the unusually busy young songwriter, with an important show opening in New York on January 21.

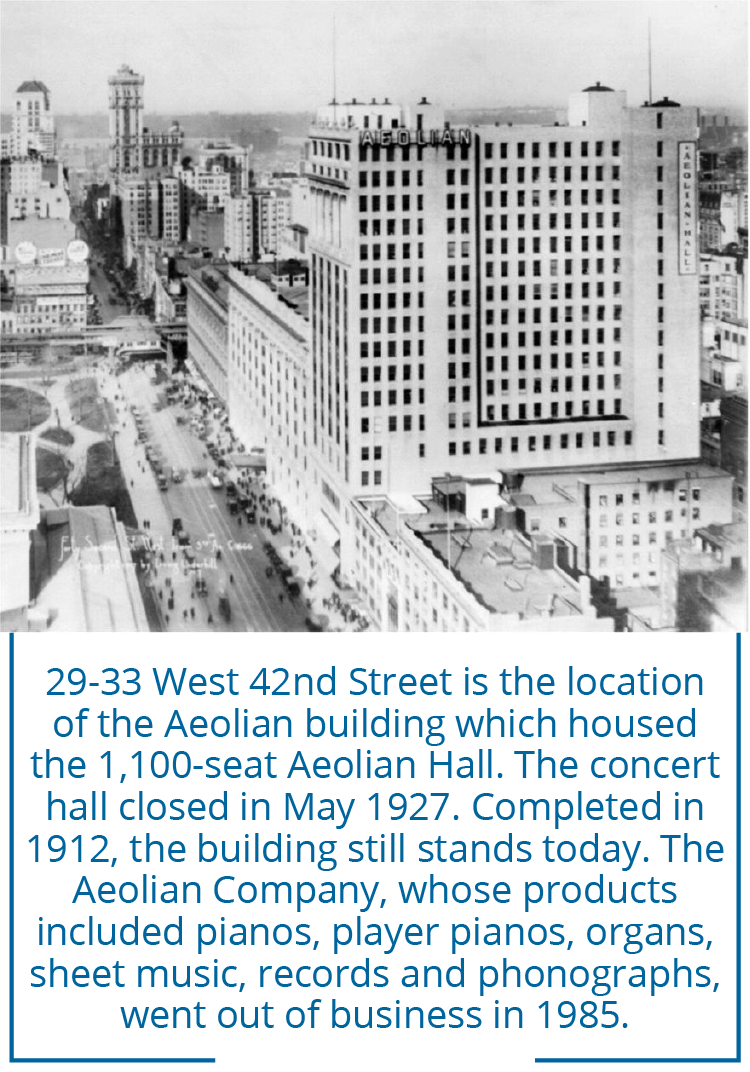

Whiteman’s finely-tuned publicity machine invited music critics and writers to rehearsal/luncheons in the Palais Royal nightclub, where the ambience was very much morning-after-the-night-before, and where an enlarged Whiteman band rehearsed the newly minted Rhapsody in Blue. By February 12, many more celebrities from all walks of life had been invited (Godowksy, Kreisler, Sousa, Stokowski, Damrosch and Bloch were among the musicians) and interest was high among the general public. The 1,100 seat Aeolian Hall was full to bursting.

Whiteman’s finely-tuned publicity machine invited music critics and writers to rehearsal/luncheons in the Palais Royal nightclub, where the ambience was very much morning-after-the-night-before, and where an enlarged Whiteman band rehearsed the newly minted Rhapsody in Blue. By February 12, many more celebrities from all walks of life had been invited (Godowksy, Kreisler, Sousa, Stokowski, Damrosch and Bloch were among the musicians) and interest was high among the general public. The 1,100 seat Aeolian Hall was full to bursting.

Structurally, Gershwin’s score is built around the Big Tune, which he initially hints at, then cunningly holds back until more than halfway through. The other five melodies all fall into some variant on the four-plus-four-bar popular song format, usually left without a closing chord, so that the melodies could be strung together in a variable sequence. The score and the way it sounds are infinitely malleable and have allowed each generation to reformat the piece to its own taste. The most frequently heard version is the expanded symphonic score that Ferde Grofé made in 1942.

The June 1924 acoustic recording that Gershwin made with the original Whiteman band within four months of the première – full of Roaring Twenties exuberance and insouciance – filleted the score by one third. However, the concert (and its repeats on March 7 and in Carnegie Hall in April and November) likely included more improvisation from Gershwin, bringing the idiom a little closer to the spirit of jazz. Three years later, the Whiteman band, by now with different personnel, re-recorded the work with an altogether different sound, taking advantage of electric recording technology. Each subsequent version nudges Gershwin’s score in one direction or another, towards the concert hall, or towards its origins as music for jazz dance band. Now just two years shy of a century in front of the public, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue has moved from being the only memorable new piece in a concert titled ’An Experiment in Modern Music’ to national icon.

The June 1924 acoustic recording that Gershwin made with the original Whiteman band within four months of the première – full of Roaring Twenties exuberance and insouciance – filleted the score by one third. However, the concert (and its repeats on March 7 and in Carnegie Hall in April and November) likely included more improvisation from Gershwin, bringing the idiom a little closer to the spirit of jazz. Three years later, the Whiteman band, by now with different personnel, re-recorded the work with an altogether different sound, taking advantage of electric recording technology. Each subsequent version nudges Gershwin’s score in one direction or another, towards the concert hall, or towards its origins as music for jazz dance band. Now just two years shy of a century in front of the public, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue has moved from being the only memorable new piece in a concert titled ’An Experiment in Modern Music’ to national icon.

This evening’s arrangement by music director Matt Catingub is made for eleven-piece big band, featuring nine horns, bass, drums and piccolo trumpet solo. The ethos behind the arrangement is to have the piccolo trumpet as a secondary soloist in the manner of the Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 1. Mr Catingub’s arrangement honors the feel of the original 1924 version – notably its klezmer and jazz roots – while keeping some coloristic elements of the 1942 orchestral version. Enjoy!

This evening’s arrangement by music director Matt Catingub is made for eleven-piece big band, featuring nine horns, bass, drums and piccolo trumpet solo. The ethos behind the arrangement is to have the piccolo trumpet as a secondary soloist in the manner of the Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 1. Mr Catingub’s arrangement honors the feel of the original 1924 version – notably its klezmer and jazz roots – while keeping some coloristic elements of the 1942 orchestral version. Enjoy!