QUARTET IN E-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 33, NO. 2, (HOB.III.38) (THE JOKE)

Joseph Haydn

(b. Rohrau, Lower Austria, March 31, 1732; d. Vienna, May 31, 1809)

Composed 1781; 18 minutes

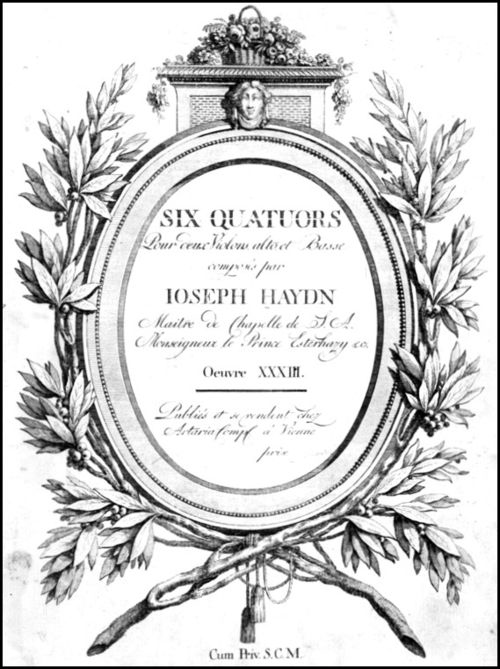

In music, what goes around comes around. Towards the end of 1781, Haydn kick-started a crowdfunding platform. There are to be six “entirely newly produced quartets,” he said in his pitch, “written in an entirely new special manner.” In return for their pledges, backers (read ‘patrons’) would receive pre-publication manuscript copies and their names included in the list of subscribers to the printed edition.

In music, what goes around comes around. Towards the end of 1781, Haydn kick-started a crowdfunding platform. There are to be six “entirely newly produced quartets,” he said in his pitch, “written in an entirely new special manner.” In return for their pledges, backers (read ‘patrons’) would receive pre-publication manuscript copies and their names included in the list of subscribers to the printed edition.

Haydn’s crowdfunding platform

Haydn’s crowdfunding platform

From one of the surviving fundraising letters for Haydn’s Op. 33, dated Dec. 3, 1781, to Swiss writer Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801) in Zürich:

Most learned Sir and Dearest Friend!

I love and happily read your works. As one reads, hears and relates, I am not without adroitness myself, since my name (as it were) is known and highly appreciated in every country. Therefore, I take the liberty of asking you most courteously to place a small order. Since its known to me that in Zürich and Winterthur there are many gentlemen amateurs and great connoisseurs and patrons of music, I certainly cannot conceal that I am issuing by subscription for the price of 6 ducats an opus consisting of 6 Quartets, accurately copied, for 2 violins, alto viola, violoncello concertante, of an entirely new special kind, since I have written none for ten years” [emphasis in the original].

I did not want to fail to offer these to the great patrons of music and the amateur gentlemen. Subscribers who live abroad will receive them before I print the works. Please don't take it amiss that I bother you with this request; if I should be fortunate enough to receive an answer containing your approval, I would most appreciate it, and remain,

Most learned Sir,

Your ever obedient

Josephus Haydn [signed by Haydn]

Fürst Estorházischer Capell Meister

When published, the new quartets, combining accessibility with artistic excellence, immediately created a stir. Mozart, just launching a career as a freelance composer in Vienna when the quartets were first published in 1782, admired their compactness, their perfect balance of character, form and technique, and the way in which Haydn gives all four instruments equal importance. He painstakingly composed a set of six in emulation of Haydn’s Op. 33, with several of Haydn’s movements clearly used as direct models.

The opening movement of the E-flat Quartet is built rigorously on the good-natured rhythmic figure of its first few bars. Very little in the movement has to do with anything other than this thematic material. In the Scherzo, Haydn’s focus moves from high culture to folk culture, to accessibility and innovation. In it, Haydn makes the first documented use of the wavy line in a score to indicate that typically Viennese glissando (slide), famous shortly afterwards from the waltzes of the Strauss family and others. He also plays with the anticipated eight-bar phrase structure by adding a bar and upsetting any feeling of predictability. The mood shifts again in the highly sophisticated variations of the slow movement, where a transparent, eight-measure melody is shared among the instruments in every possible permutation. The E-flat Quartet is often called The Joke because of the witty ‘false ending’ of its rondo finale. Here, in a touch of self-mockery perhaps, Haydn deconstructs the much-repeated theme, giving us the melody phrase by phrase, each separated by a bar of silence. Three more bars of silence and he now gives us the opening phrase again, pianissimo—and with it,

a good chuckle.