PIANO QUARTET IN E-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 47

Robert Schumann

(b. Zwickau, Saxony, June 8, 1810; d. Endenich, nr. Bonn, July 29, 1856)

Composed 1842; 28 minutes

1842 was Robert Schumann’s year of chamber music. It followed 1839, a year of mostly piano music, 1840, his year for song, and 1841 when he produced his first symphonies. 1842 proved to be exceptionally productive. After intensive study of the great string quartets of the past, Schumann completed three of his own. He followed these with the great Piano Quintet, Op. 44, taking just five days for the sketches and two weeks for the score. A month later, also after five days of sketches, he completed the Piano Quartet, Op. 47. Before the year’s end, he turned to the piano trio and the work that would later become the Fantasiestücke, Op. 88.

Both the Quintet and the Quartet are in the key of E-flat. While the Piano Quintet had no precedent, the Piano Quartet followed the two by Mozart and one by Beethoven (a transcription of the Quintet for piano and winds, Op. 16). Schumann had first explored these works in 1828 while ostensibly pursuing law studies at the University of Leipzig. There, he formed his own piano quartet to read through several piano quartets and trios, often with an audience of musicians present to share the discovery. He even drafted a C minor piano quartet of his own, now catalogued as WoO 32 and published in 1979.

Schumann wrote the E-flat Piano Quartet some 14 years later. It is more closely related to his own Piano Quintet than to the earlier work or to the classical quartets he had studied. Both the Piano Quartet and Quintet put the piano front and center in the texture, as in a miniature piano concerto. Because of its reduced forces, the Quartet has a more intimate scale than the Quintet. The first movement opens with a foreshadowing of the terse main theme that is to propel the movement energetically forward. The rising second theme gives an opportunity for Schumann to employ his new-found interest in counterpoint. Development and recapitulation are skillfully woven together in this classically constructed movement. Although the dashing passagework of the Scherzo has something of a Mendelssohn-like lightness and buoyancy, a gathering cloud seems to hang over its minor-key activity.

The slow movement is the emotional high point of the quartet. It opens with a gloriously soaring cello theme, by way of tribute to the cello-playing Count Matvei (or Mathieu) Wielhorsky, who commissioned the music – and owned both an Amati and a Stradivari cello. Although an amateur, Wielhorsky gave the first performance of the quartet along with Ferdinand David (violin), Niels Gade (viola) and Clara Schumann (piano), for whom the piece was designed. Brahms paid tribute to the eloquence of Schumann’s writing by modelling the slow movements of his C minor Piano Quartet and B-flat Piano Concerto on this opening theme. Extra resonance is provided in this movement when the cellist tunes down the lowest string to B-flat, the home key of the movement. (The time taken to do so also allows the viola to take over the restatement of the heart-warming melody). The finale bursts onto the conclusion of the slow movement, exuberantly unleashing melody upon melody, contrapuntally working them through with a glee that few who have tackled the art of counterpoint have brought to their hard-won results.

Schumann had high hopes of building a career as a pianist-composer around the time he was turning 20. A letter from piano pedagogue Friedrich Wieck (his future father-in-law) promised that, with disciplined training and study with Wieck, he could, within three years, become a greater artist than either Hummel or Moscheles, two of the most celebrated pianists of the day. Schumann’s plan was to follow studies with Wieck with a year in Vienna, under the guidance of Moscheles. By 21, his daily regime started at 7:00 AM with three hours practice of Chopin, followed at 11:00am with an hour of Czerny’s trill studies and Hummel’s finger exercises – and then an afternoon practicing other music.

Schumann had high hopes of building a career as a pianist-composer around the time he was turning 20. A letter from piano pedagogue Friedrich Wieck (his future father-in-law) promised that, with disciplined training and study with Wieck, he could, within three years, become a greater artist than either Hummel or Moscheles, two of the most celebrated pianists of the day. Schumann’s plan was to follow studies with Wieck with a year in Vienna, under the guidance of Moscheles. By 21, his daily regime started at 7:00 AM with three hours practice of Chopin, followed at 11:00am with an hour of Czerny’s trill studies and Hummel’s finger exercises – and then an afternoon practicing other music.

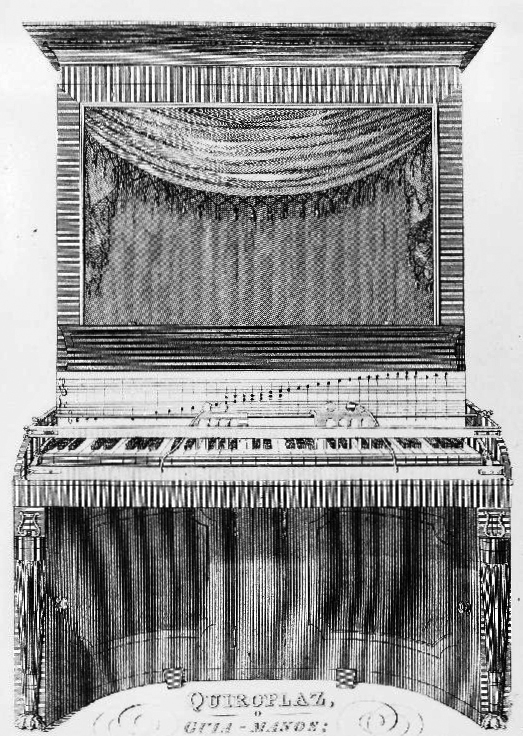

His diaries from the time, however, speak of ‘an ever-worsening weakness’ or ‘laming’ of the middle finger of his right hand. The cause can only have been aggravated using a finger-strengthening device patented by German pianist and pedagogue Johann Bernhard Logier (1777-1846), known as a chiroplast, which Schumann experimented with in Heidelberg while beginning law studies, as did his piano duo partner at the time. Schumann referred to Logier’s ‘hand-director’ mechanism, as a ‘cigar-mechanism.’ By October 1831, the numbness in his middle finger had become the source of ‘inner struggles.’

In desperation, the young pianist tried some form of ‘electrical’ therapy and homeopathy, even, on the recommendation of a Professor Kühl, animal baths, involving the insertion of the hand into the still warm innards of a freshly killed animal carcass. A year later, he wrote about his now permanently damaged finger to his mother: “for my part, I’m completely resigned and deem it incurable.” His dreams of a career as a piano soloist were dashed, even if his hopes as a composer were now confirmed – “I can compose without it.”

In desperation, the young pianist tried some form of ‘electrical’ therapy and homeopathy, even, on the recommendation of a Professor Kühl, animal baths, involving the insertion of the hand into the still warm innards of a freshly killed animal carcass. A year later, he wrote about his now permanently damaged finger to his mother: “for my part, I’m completely resigned and deem it incurable.” His dreams of a career as a piano soloist were dashed, even if his hopes as a composer were now confirmed – “I can compose without it.”

The finger-strengthening chiroplast. Pianist’s hands are inserted into the two, domed, claw-like devices which move on a runner the full length of the keyboard.