QUARTET NO. 11, IN C MAJOR, OP. 61, B.121

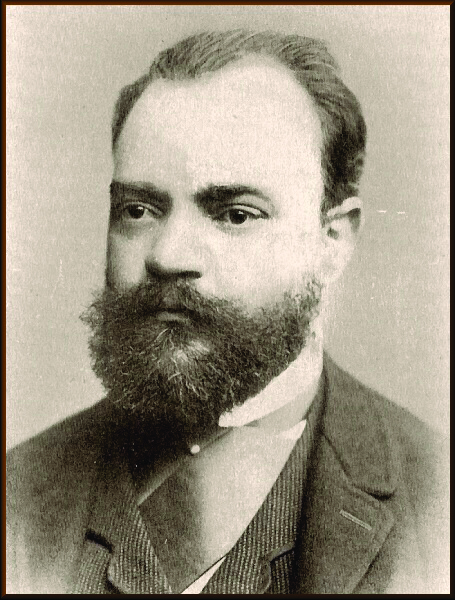

Antonín Dvorák

(b. Nelahozeves, Bohemia, September 8, 1841; d. Prague, May 1, 1904)

Composed 1881; 38 minutes

Antonín Dvorák composed the eleventh of his 14 string quartets for Joseph Hellmesberger, the Viennese court Kapellmeister, concertmaster of the Vienna State Opera and Conservatory director, the very pillar of the Viennese musical establishment. Hellmesberger’s string quartet had held a reputation as Vienna’s finest for over three decades when they first began to perform music by Dvorák. It was a good time for the musician from provincial Prague. After four decades of poverty and state stipends, his music was now being championed by Brahms and the influential Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick. His music was being published by a German publisher, thanks to Brahms’s recommendation, and the Vienna Philharmonic Society had just requested a new symphony. At the beginning of October 1881, he immersed himself in a new opera for the inauguration of the new National Theater in Prague, reassuring Hellmesberger that he would work on the opera in the mornings and the quartet in the afternoons. By the middle of November, he opened a Viennese newspaper. “I see in the papers that on December 15, Hellmesberger is to perform my new quartet, which does not yet exist,” he wrote with some humor to a friend. “There is nothing left for me to do but to compose it!”

Antonín Dvorák composed the eleventh of his 14 string quartets for Joseph Hellmesberger, the Viennese court Kapellmeister, concertmaster of the Vienna State Opera and Conservatory director, the very pillar of the Viennese musical establishment. Hellmesberger’s string quartet had held a reputation as Vienna’s finest for over three decades when they first began to perform music by Dvorák. It was a good time for the musician from provincial Prague. After four decades of poverty and state stipends, his music was now being championed by Brahms and the influential Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick. His music was being published by a German publisher, thanks to Brahms’s recommendation, and the Vienna Philharmonic Society had just requested a new symphony. At the beginning of October 1881, he immersed himself in a new opera for the inauguration of the new National Theater in Prague, reassuring Hellmesberger that he would work on the opera in the mornings and the quartet in the afternoons. By the middle of November, he opened a Viennese newspaper. “I see in the papers that on December 15, Hellmesberger is to perform my new quartet, which does not yet exist,” he wrote with some humor to a friend. “There is nothing left for me to do but to compose it!”

Three weeks later, the quartet was complete. The mood is at once intimate, with an affirmative theme that is rich in potential for development. It soon plunges dramatically into the minor and Dvorák explores the resulting major-minor ambiguity throughout the opening movement. The music travels through a range of emotions from the joyous to the wistful. The spacious slow movement, one of Dvorák’s generously romantic utterances, again successfully exploits a frequent major-minor shift in modality. It is based on a discarded sketch for the F major Violin Sonata, Op. 57 of the previous year. Similarly – probably to hasten completion of the work – the third and fourth movements incorporate themes from a Polonaise for cello and piano that Dvorák was working on a year or two earlier. The Scherzo brings a return to the urgency of the opening movement and an echo of a motif from its opening theme. In its brilliant trio section, Dvorák allows his love for folk-like themes to surface, though the development of the material remains securely within the traditions of the Viennese quartet. Dvorák knew he was treading a fine line between national feeling and an international musical language. “Viennese audiences seem to be prejudiced against a composition with a Slav flavor,” he had written to conductor Hans Richter just the previous year, recognizing that political tensions could intrude on concert hall performance. In the finale, rigorous development of musical motifs continues as the driving force behind exuberant, technically demanding, Slavonic-colored music.

— Program notes © 2023 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: khnotes@sympatico.ca