OCTET IN F MAJOR, FOR CLARINET, BASSOON, HORN, TWO VIOLINS,

VIOLA, CELLO AND BASS, OP. 166, D. 803

Franz Schubert

(b. Vienna, Austria, January 31, 1797; d. Vienna, November 19, 1828)

Composed 1824; 63 minutes

When Ignaz Schuppanzigh, the leading Viennese violinist and entrepreneur, brought together eight musicians to give the première of Schubert’s Octet, he could call on much the same loyal musicians who had given the première of the Beethoven Septet almost a quarter century earlier. The clarinetist, however, was now Ferdinand, Count Troyer, Archduke Rudolf’s steward, a skilled musician who commissioned the Octet from Schubert with the stipulation that it closely resemble Beethoven’s Septet – that composer’s most popular work during his lifetime. Both works are in the serenade/divertimento tradition, with six rather than four movements, and both exude a feeling of well-being and relaxation, an easy-going Gemütlichkeit. Schubert maintains a similar key relationship to that of the Beethoven septet, from one movement to the next. Like Beethoven, he includes both scherzo and minuet (though reversed in order) and chooses a theme and variations as the fourth movement. He also follows Beethoven’s lead by including a slow introduction to both first and last movements. Schubert does, however, add a second violin to Beethoven’s single violin, completing the string quartet foundation to his mixed ensemble of strings and winds.

Schubert took the month of February 1824 to fulfill the commission, delivering a work designed to appeal to both listeners and players, but which, despite its outward resemblance to the Beethoven Septet, still speaks with an individual voice. The Octet was written around the time he composed the A minor (D. 804) and much of the D minor

(D. 810) Death and the Maiden string quartets, both works designed for publication and performance by Schuppanzigh’s quartet, rather than the private performances his earlier quartets had received. The Octet was first played at a gathering in Troyer’s apartments in the spring of 1824, when Troyer played clarinet, together with Schuppanzigh’s customary musicians for the Beethoven Septet.

Imitation in the Octet is, indeed, the sincerest form of flattery. Schubert worshipped Beethoven and – like Schuppanzigh – was to be a pallbearer at his funeral in 1827. Both works open with an 18-measure Adagio introduction to the first movement. Schubert builds anticipation for what is to follow and adds unity by incorporating a short, dotted figure in both sections. Indeed, the dotted rhythm continues to bring a feeling of unity throughout each of the movements of the Octet. The luxuriant, seamless melody that opens the slow movement is given to the clarinet, and the modulations that ensue could only have come from Schubert’s pen. An exuberant scherzo follows, rustic and unbuttoned, maybe even a little prophetic of Bruckner. The melody of the variation movement that Schubert provides next is shared by both violin and clarinet and is drawn from a love duet from his comic opera Die Freunde von Salamanka (The Friends from Salamanca). Schubert here provides seven variations to Beethoven’s five. A graceful minuet then leads to the somber, mysterious introduction to the finale. This culminates in a vigorous march-like theme which is given a thorough working through. It’s a fitting conclusion to a piece that is conceived on a symphonic scale, yet it maintains the cheerful grace of a true piece of chamber music played among friends.

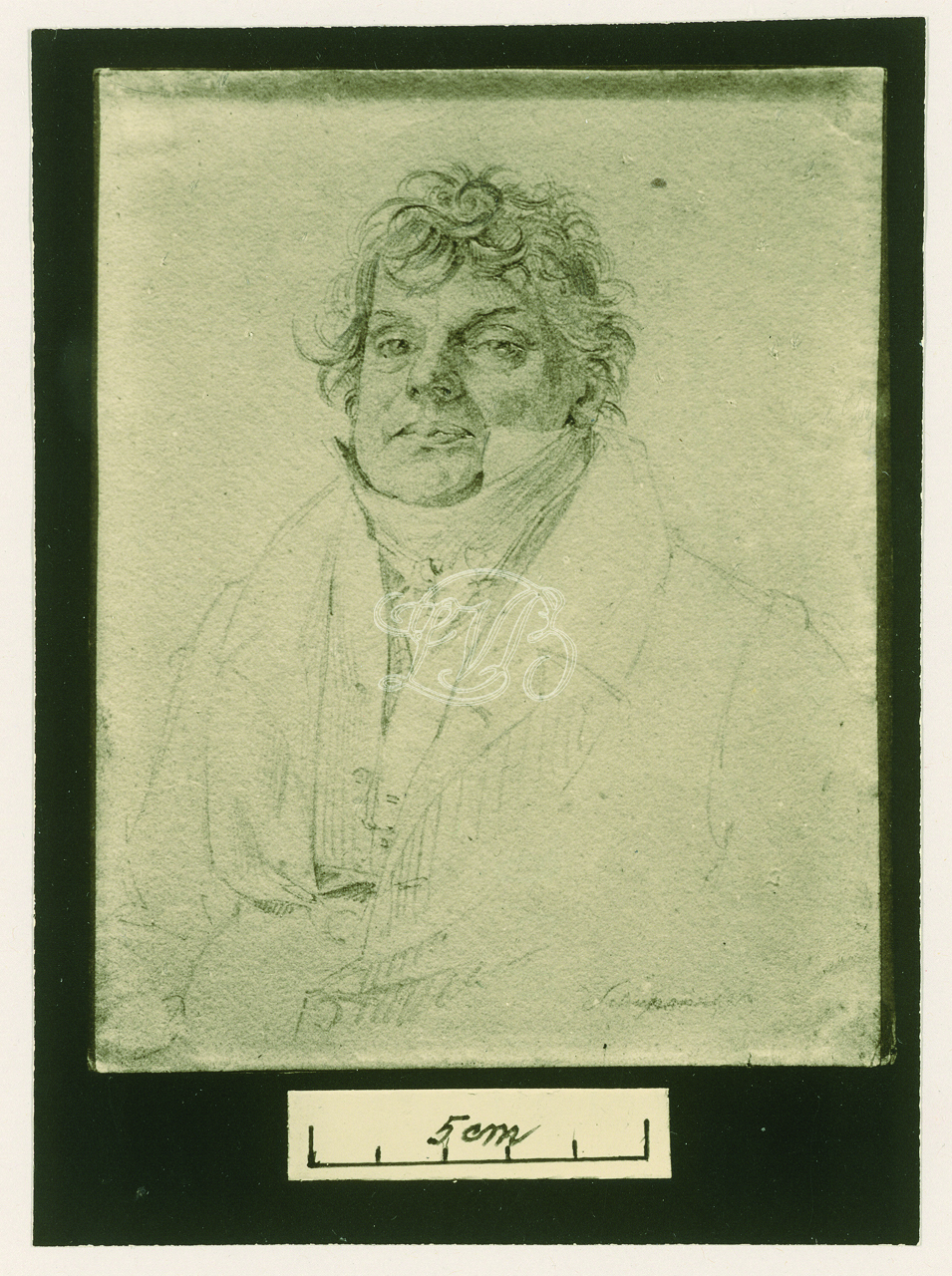

Background Briefing: Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830)

Background Briefing: Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830)

• Best remembered for his connection with Beethoven, Viennese violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh led the premières of many string quartets, the Archduke trio and Beethoven’s Ninth. He collaborated with Beethoven on all his quartets from Op. 18 through Op. 135.

• Mid-1790s. Forms his first string quartet for concerts at Prince Lichnowsky’s Viennese residence. Beethoven is believed to take violin lessons with him.

• 1804-5. Starts the first public quartet concert series in Vienna, likely including Beethoven’s Op. 59 Razumosvky quartets. The series lasts for three seasons.

• 1808. Invitation from Count Razumovsky to form “the finest string quartet in Europe.” It lasts six years, adding to Schuppanzigh’s widespread reputation of leading the only ensemble that could reveal the beauties of Beethoven’s music.

• 1808. Invitation from Count Razumovsky to form “the finest string quartet in Europe.” It lasts six years, adding to Schuppanzigh’s widespread reputation of leading the only ensemble that could reveal the beauties of Beethoven’s music.

• 1816. Razumovsky’s city residence and with it, his fortune, goes up in flames. Schuppanzigh is drawn to the flourishing musical life of St. Petersburg where he promotes Beethoven’s music in palaces, salons, halls and the Philharmonic

Society orchestra.

• 1823. Returns to Vienna after seven years based in St. Petersburg, also touring Poland, Prussia and Northern Germany. Re-forms his ‘Razumovsky’ quartet, presenting a groundbreaking series of public chamber music concerts. These omit the customary vocal selections and virtuoso solo showpieces and elevate the status of the string quartet. No longer primarily hausmusik for upper- and middle-class Viennese amateurs, the string quartet now becomes the center of attention for an audience of chamber music connoisseurs.

• 1823-5. Presents earlier quartets by Haydn and Mozart in addition to the latest quartets by Beethoven. These, plus Mozart quintets, Beethoven string trios, quintets and the ever-popular Septet form the backbone of his programming. ‘Classical’ music becomes a term widely used in Vienna. Schuppanzigh’s concerts are available by season subscription only; no drop-ins. An attentive audience and a dedicated quartet stimulate Beethoven in his lone path through the challenging late quartets.

• 1823-5. Presents earlier quartets by Haydn and Mozart in addition to the latest quartets by Beethoven. These, plus Mozart quintets, Beethoven string trios, quintets and the ever-popular Septet form the backbone of his programming. ‘Classical’ music becomes a term widely used in Vienna. Schuppanzigh’s concerts are available by season subscription only; no drop-ins. An attentive audience and a dedicated quartet stimulate Beethoven in his lone path through the challenging late quartets.

• Remains one of Beethoven’s few ongoing friends, despite receiving regular jokes about his obesity. Beethoven dedicates a choral piece Lob auf den Dicken, WoO 100 (In Praise of the Fat One) to Schuppanzigh in 1801. The

maestro’s return to Vienna is greeted by Beethoven’s canon, WoO 184 “Falstafferl, lass dich sehen” (Little Falstaff, welcome back).

• 1825. The much-delayed, poorly rehearsed première of Op. 127, the first of the late Beethoven quartets, upsets subscribers and irritates Beethoven. Two rival violinists present Op. 127 in five concerts in March and April, sometimes playing the quartet twice to the same audience. Press and journal reports question Schuppanzigh’s playing, mentioning the effect of his corpulence.

• 1826-30. Continues with his subscription concerts, also arranging special concerts for the premières of Opp. 130 and 131. The core string quartet members and associates remain loyal and continue to specialize in string quartets, despite holding leading roles among the principal Viennese musical organizations. They increasingly help the ailing Beethoven with editorial matters, copying parts, proofreading and the publication process for the late quartets. Together with Schuppanzigh, they become (in the words of musicologist John M. Gingerich) Beethoven’s eyes and ears on the city of Vienna.

• 1827. Premières Schubert’s A-minor Quartet, D. 804. The shy Schubert, now on good terms with the renowned violinist, dedicates the work on publication to his friend. Schuppanzigh also premières Schubert’s Piano Trio in B-flat Major, D. 898. The première of the already privately performed Octet, however, is left until April 16, 1827, the closing subscription concert of the 1826-7 season.

• After borrowing heavily against his Amati violin and a small pension from Razumovsky, having been without a permanent paid position in Vienna for many years, Schuppanzigh is appointed to the Court Chapel orchestra (Hofmusikkapelle) in 1827 and then concertmaster to the Court Opera (Hofopermorchester) the following year. With the death of Franz Weiss, his longtime violist, Schuppanzigh regroups and announces a series of four subscription concerts March 7 to 28, 1830. Schuppanzigh himself dies before the first concert, March 2, 1830, at age 53.

— All program notes © 2023 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: khnotes@sympatico.ca