VARIATIONS BRILLANTES ON A THEME FROM LUDOVIC BY HÉROLD, OP. 12

Composed 1833; 9 minutes

BARCAROLLE IN F-SHARP MAJOR, OP. 60

Composed 1845-6; 9 minutes

IMPROMPTU IN A-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 29

Composed c1837; 4 minutes

SCHERZO NO. 2, IN B-FLAT MINOR, OP. 31

Composed 1837; 10 minutes

Fryderyk Chopin (b. Żelazowa Wola, nr. Warsaw, Poland, March 1, 1810; d. Paris, October 17, 1849)

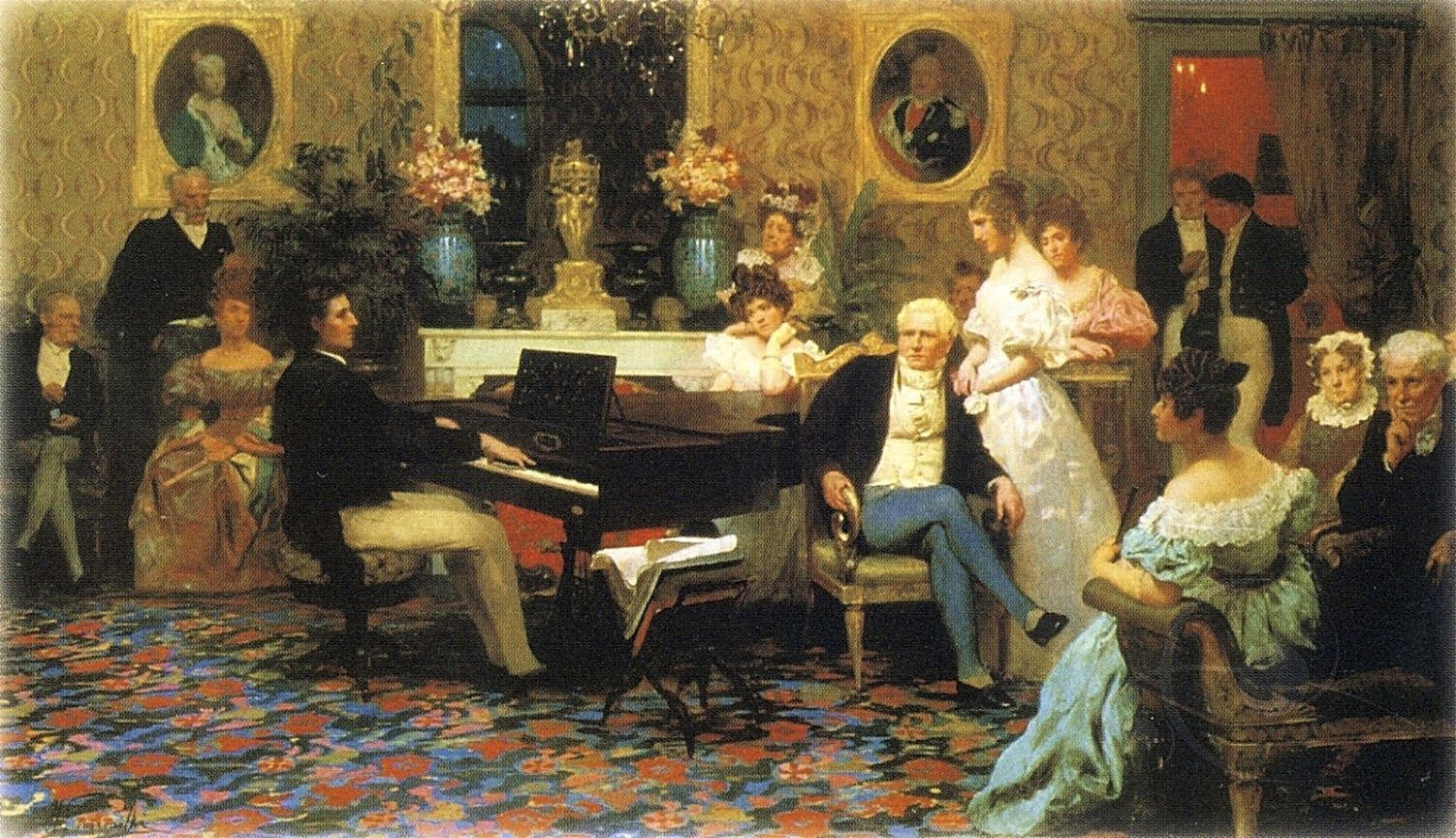

Chopin playing in a salon of the aristocratic Polish family Radziwiłł in 1829, two years before leaving for Paris.Chopin shied away from the concert platform when public piano recitals were beginning to thrive throughout the European capitals. He only gave around 50 concerts in his entire lifetime, from his earliest childhood in Warsaw to the performances he gave in Britain a year before his death at the age of just 39. The intimate salon rather than concert hall was where Chopin excelled. And the Variations brillantes, Op. 12, that he wrote in Paris in 1833 after hearing the première of Ludovic, the last of numerous operas by Ferdinand Hérold, became his calling-card for a while. Choosing a simple cavatina with an attractive theme, Chopin announces his presence with a resolute fanfare, then prolongs the wait with nocturnal musing interspersed with brilliant passagework, building to the theme itself. Its potential begins to be revealed in the first of four variations, delicately drawn and characterful. Two scherzando variations then surround a decorative, nocturnal third, and the set concludes with a brilliant coda. The following year, 1834, Chopin proudly sent his sister his three published Op. 15 Nocturnes, only to find that the volume also contained variations on the same cavatina as his own Op. 12 by three other lions of the Parisian keyboard: Herz, Hünten and Pixis.

Chopin playing in a salon of the aristocratic Polish family Radziwiłł in 1829, two years before leaving for Paris.Chopin shied away from the concert platform when public piano recitals were beginning to thrive throughout the European capitals. He only gave around 50 concerts in his entire lifetime, from his earliest childhood in Warsaw to the performances he gave in Britain a year before his death at the age of just 39. The intimate salon rather than concert hall was where Chopin excelled. And the Variations brillantes, Op. 12, that he wrote in Paris in 1833 after hearing the première of Ludovic, the last of numerous operas by Ferdinand Hérold, became his calling-card for a while. Choosing a simple cavatina with an attractive theme, Chopin announces his presence with a resolute fanfare, then prolongs the wait with nocturnal musing interspersed with brilliant passagework, building to the theme itself. Its potential begins to be revealed in the first of four variations, delicately drawn and characterful. Two scherzando variations then surround a decorative, nocturnal third, and the set concludes with a brilliant coda. The following year, 1834, Chopin proudly sent his sister his three published Op. 15 Nocturnes, only to find that the volume also contained variations on the same cavatina as his own Op. 12 by three other lions of the Parisian keyboard: Herz, Hünten and Pixis.

The contrast with the refinement of the later Barcarolle in F-sharp major, Op. 60, is considerable. Here, the main melody of Chopin’s gently undulating Venetian boat song is sung in thirds and sixths over a distinctive accompaniment. This is traditionally in 6/8 meter, with a heavier push on the first beat and gentler lift on the fourth. Now, though, Chopin stretches his barcarolle to 12/8, creating a broader, more languorous feeling of time and space. It is his only barcarolle, a magnificent late work from his maturity. As the melodies of Chopin’s gondoliere are decorated with the finest filigree, with trills and double trills in thirds, the piece’s ornamentation complements the richness of the harmonies which are probing and exploratory. The climax comes as the main theme returns, its rocking accompaniment now in forceful octaves as the passion of the voyage is overcome by an almost frightening power. This unwinds, over the course of a beautifully controlled coda, to a whisper, and then concludes abruptly with four decisive octaves.

Generally longer than the Nocturnes, but shorter than the Ballades or Scherzos, Chopin composed his four Impromptus over a nine-year period. They are, essentially, autonomous works, like the Impromptus of Schubert. Still, they do share underlying thematic links. All create something of the spirit of improvisation, although sketches and drafts reinforce the fact that Chopin worked hard to create this spontaneity. The exuberance of the outer sections of the Impromptu in A-flat major, Op. 29, the second to be composed, have made it a favorite and sound – in French pianist Alfred Cortot’s phrase – “as though born under the fingers of the performer.”

Chopin was exploring new territory when he wrote single virtuoso scherzo movements outside the context of the symphony and piano sonata. Without the framework of contrasting sonata movements, he made a point of providing contrast within the scherzo itself. The principle behind his Four Scherzos is that of alternating dramatic and lyrical ideas. A lively outer section often encompasses a more lyrical middle episode, though the shape of each scherzo varies. In the opening turbulent outburst of the Scherzo No. 2, in B-flat minor, Op. 31, a question- and answer-like statement broadens into one of Chopin’s most vivid, plunging and expansive melodies. Dramatic contrast is present from the outset and continues for all three sections of a work that Robert Schumann referred to as ‘Byronic.’ Chopin maintains a feeling of spontaneity and creativity with a structure that brings a surprise at every turn. A triumphant coda culminates in the key of D-flat major rather than in the home key of B-flat minor, resolving the tensions within one of Chopin's most loved and magisterial works.

— All program notes copyright © 2024 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: khnotes@sympatico.ca