Composed 1893; 27 minutes

The String Quartet comes from the beginning of Debussy’s maturity and the influences he absorbs in its pages are extraordinary. He develops the cyclical form of his senior colleague César Franck in the way an impressionist painter would capture different facets and varying hues of the same object on a single canvas. A Javanese gamelan he encountered in Paris at the 1889 World Exposition leads to the exotic sounds of the second movement. “Harmony formed out of melodies” heard in a mass by Palestrina leads Debussy to an even stronger influence throughout the quartet, that of the old church modes. His quartet also reveals other influences. But through it all, Debussy’s voice emerges with passion and clarity, the very hallmarks of French chamber music writing. His quartet introduces modernity into a musical form that was, perhaps, the least likely vehicle to accommodate its revolutionary impact.

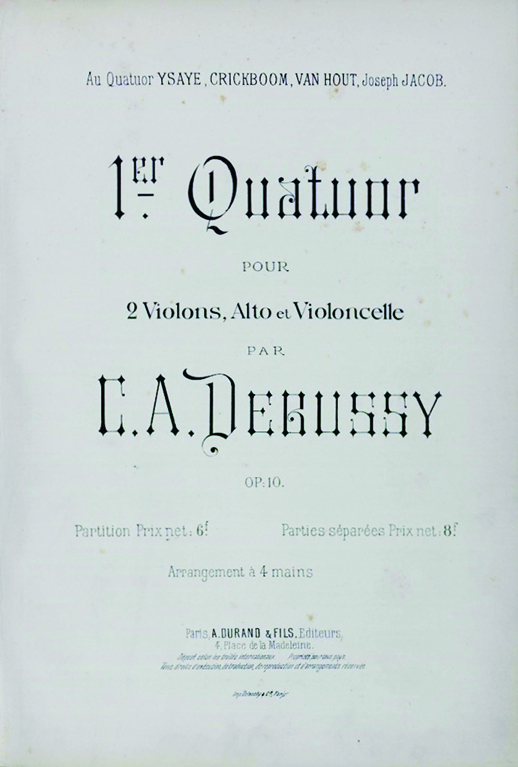

It’s the masterpiece that Debussy titled ‘First String Quartet’ with which the Viano Quartet opens tonight’s concert. The Viano does not have a second quartet by Debussy in its repertoire. In fact, you won’t find a string quartet that does. But the French composer did promise to write a second quartet for his fellow-composer and sometime benefactor Ernest Chausson. “I’ll write another one which will be for you, in all seriousness for you,” Debussy wrote in February 1894, a few weeks after the première of the First.

“In all seriousness?” Substitute the word ‘irony’ and you’ll get the picture. As for the title of the quartet that Debussy published – ‘First String Quartet, in G minor, Op. 10’ – that’s irony again. Debussy never gave any other composition an opus number and never specified a key elsewhere. The non-conformist young composer, confident in his own musical voice, gave his music some of the most poetic titles in the business. Debussy’s quartet—his only quartet—is anything but conformist. It’s a work of transcendent beauty and infinite subtlety of timbre, thematic variation and harmony.

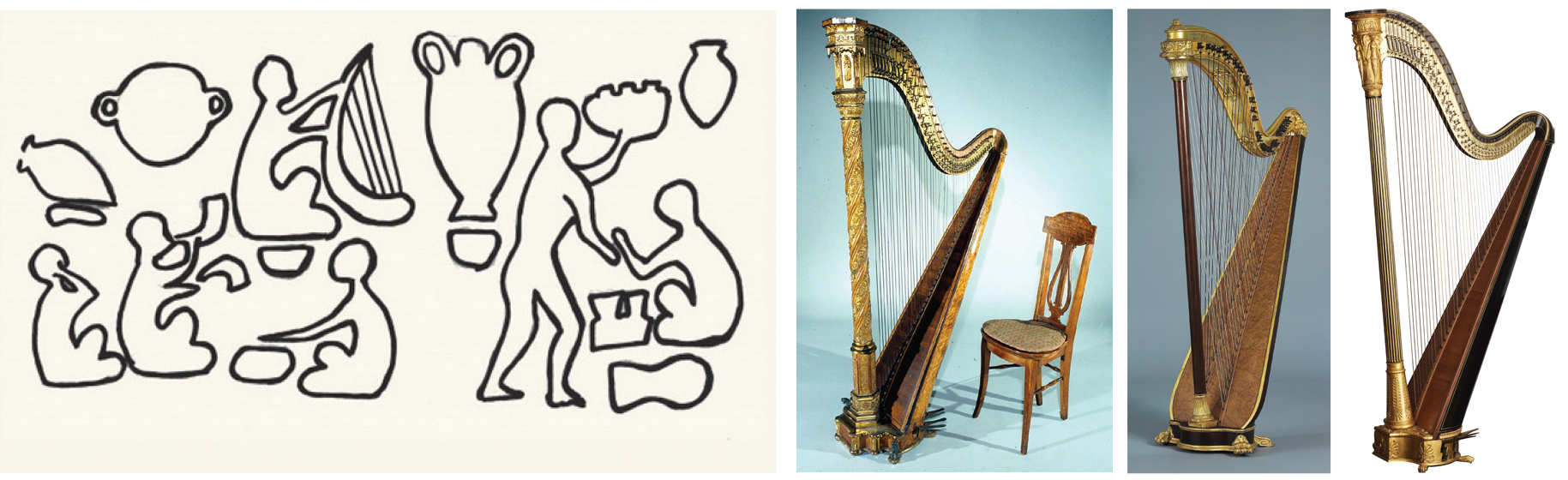

The Choga Mish Sextet (not appearing tonight): six musicians portrayed on pottery found at the Čoga Miš archaeological site in Persia (Iran), 3300-3100 B.C.E. This includes a representation of our planet’s oldest known harpist playing one of the most ancient and universal musical instruments. Over the millennia, the variety of harps has been almost infinite. Their construction, though, is basically the same: strings of varying length stretched over a frame, to be plucked by the fingers.

Throughout the 19th century, the Érard company, with companies in both Paris and London, continued to make advances in harp design. In 1810, Sébastien Érard patented the Érard double-action harp with seven pedals (Patent No. 3332). Improving upon his single-action pedal model, the harpist now had the ability to sharpen each string twice, simultaneously in every octave. In the raised position, all the ‘A’ strings on the instrument are tuned to A-flat. Depressing the pedal one notch will stretch all these strings to A-natural. A further notch will stretch each string even higher, to an A-sharp. In 1835, Sébastien’s nephew Pierre Érard brought out a Mark 2 design, with 46 strings and steel lower strings, instruments whose use extended well into the next century.

As the harp gradually began to be introduced to the orchestra in the 19th century, it was only equipped with single-action pedals. This increasingly became a challenge as the century progressed, leading towards the complex harmonies of Wagner, Richard Strauss, Fauré, Franck and company. The two-rank, cross-strung harp, popular among Spanish musicians in Renaissance times, had been ‘re-invented’ and patented as early as 1845 in Paris. It was revived as the harpe chromatique sans pédales (the chromatic harp without pedals) by Gustave Lyon of the Paris firm Pleyel, Wolff et Cie in 1897, with a re-design, more reliable tuning and fewer strings liable to break. The strings are crossed in a large X-pattern, with one series corresponding to the white notes of the keyboard, the other series to the black. There are double the number of strings than those on the pedal harp, and the harpist plays where they cross. In the early 20th century, here was a potential competitor to the dominance of the Érard pedal harp. Both Pleyel and Érard went on a commissioning spree with their rival harps.

Érard basically won the harp hostilities. The modern concert harp includes seven pedals for the feet, each with two notches controlling the pitch of its 47 strings. The lowest strings are made from steel, or steel-wound gut, and the rest are nylon or gut. All the Cs are colored red, and all the Fs, black.

Only the thumbs and first three fingers of each hand are generally used, plucking the string at an angle (which is beyond the reach of the little finger). Both feet are very busy, off and on the beat, particularly with a sudden key change from G major (one sharp) to, say, C-sharp (seven sharps).

Significant innovations in harp technology continue to be made, in the New World as well as the Old.