Composed 1746; 16 minutes

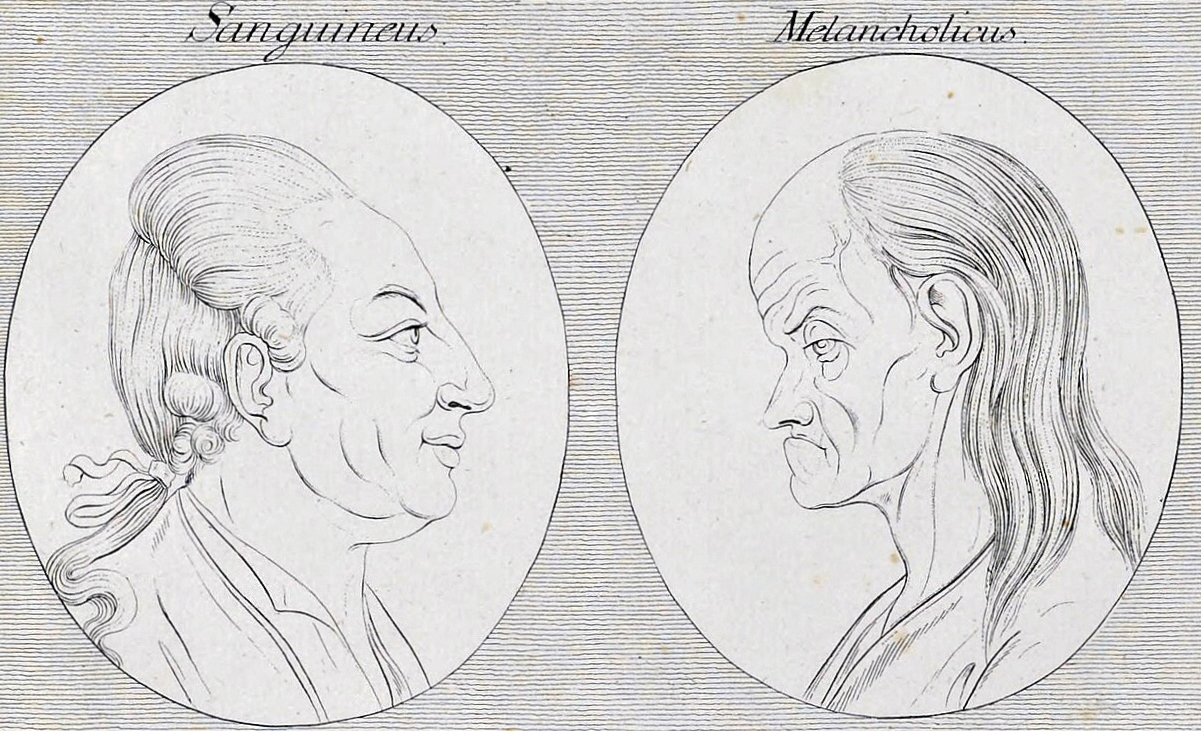

C.P.E. Bach said: “Surprise and passion can be achieved better by instruments than by voices.” That’s CPE’s answer to one of the raging debates amongst music theorists of his day: what is the fundamental nature of instrumental music and how can it be explained? With vocal music, a theorist knows where they stand. The words give the game away. Vocal music, accordingly, was ranked higher in the prestige game than the lowly harpsichord sonata or instrumental suite. In his 1746 C minor Trio Sonata, printed in Nuremberg five years later, CPE upped the ante, both in words (a Preface) and in musical notes: “It is meant to portray a conversation between a Sanguineus and a Melancholicus, who disagree throughout the first and most of the second movements. Each tries to draw the other to his own side, until they settle their differences at the end of the second movement, at which point the Melancholicus gives up the battle and assumes the manner of the other.” By the end of the Trio, their friendship is sealed when each begins to imitate the other.

For more than a quarter of a century, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Johann Sebastian’s second surviving son, worked at the Prussian court of the flute-playing Frederick the Great. Then he succeeded his godfather, Telemann, to a position of prestige, as Kantor to the Hamburg Johanneum, with teaching responsibilities and directorship of the five principal churches in Hamburg.

For more than a quarter of a century, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Johann Sebastian’s second surviving son, worked at the Prussian court of the flute-playing Frederick the Great. Then he succeeded his godfather, Telemann, to a position of prestige, as Kantor to the Hamburg Johanneum, with teaching responsibilities and directorship of the five principal churches in Hamburg.

Two of the four Temperaments, or fundamental personality types, from an 18th century woodcut by Johann Kaspar Lavater.

The sanguine = positive and hoping for good things

The melancholy = sad in feeling or expression

(It was left to Paul Hindemith to tackle the phlegmatic and the choleric in his ballet The Four Temperaments, for George Balanchine, 1946.)