Fauré’s two comparatively early piano quartets from the late 1870s and mid-1880s combine piano with string trio. The second opens with an ardent theme from the strings in unison, supported by a muscular piano accompaniment, clearly impatient to get its hands on it. This happens right away and this theme, which is almost immediately shared and broken down between the instruments, drives the movement forward in a remarkably seamless manner. Once the viola suggests a new way of presenting the surging motif, the driving force of the movement proves itself lyrical as well as dramatic. After a magical, Schubert-like shift of key, the violin further explores the potential of Fauré’s main theme, now marked tranquillo and dolcissimo (sweetly). The transformation continues without Fauré ever literally repeating himself. With its ending in G major, the overall feeling of the movement is one of constant renewal.

As in the earlier C minor Piano Quartet, Fauré places the scherzo as the second of four movements. In it, there’s a subtle rhythmic transformation of the theme of the opening movement, which has by now taken on the role of an idée fixe. There’s considerable fluidity to the meter and to the modality of the writing in this whirlwind of a movement. The slow movement provides sublime contrast to the controlled emotional turbulence of the first two movements. It is a reverie on the gentle viola theme which opens this poetically melancholy movement. “The viola would have to be invented for this Adagio if it did not already exist,” Fauré’s pupil Charles Koechlin said with a smile. The opening rumbling in the piano is a rare example in Fauré’s music of art imitating life. Here, he “almost involuntarily” recreates a childhood memory of distant church bells from the town of Cadirac. As Fauré later wrote to his wife in a 1906 letter: “Their sound gives rise to a vague reverie, which, like all vague reveries, is not translatable into words . . . Perhaps it’s a desire for something beyond what actually exists; and there, music is very much at home.” In stark contrast, the intense, impassioned finale again turns to the opening movement’s idée fixe for its musical material. Its fervent progression is quite unlike anything else in Fauré’s music. The movement’s surging, impetuous G minor triplets are relentless with cross-rhythms, cross-accents and subtle, idiosyncratic harmonic shifts. The crowning moment comes with the coda (più mosso) where Fauré asks for “yet more” and the work triumphantly transforms the prevailing theme of the quartet one final time, now in a blazing G major.

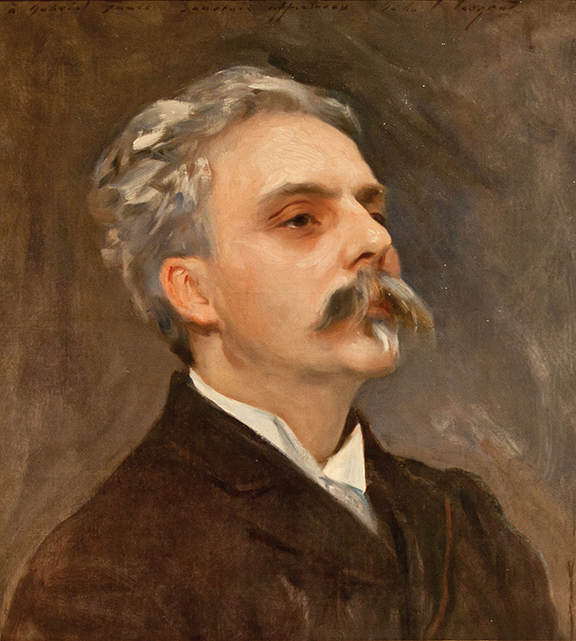

The music of French composer Gabriel Fauré blends a deep awareness of musical tradition with a secure independence of thought. At the center of his individuality lies a quite daring harmonic inventiveness. His music flows with an apparent effortlessness that, paradoxically, can only have resulted from great concentration of effort and clarity of thought. He once said that the whole process of writing music was “like a sticking door that I have to open.” Fauré’s music has a sensual beauty. It is Apollonian in its ideal. It avoids the obvious. Its demands are often virtuoso, but virtuosity for its own sake, in the way that Liszt could relish virtuosity, was light years away from Fauré’s musical world.

WHAT IS A DIVERTIMENTO?

For much of 18th century Austria, the divertimento was something of a catch-all term for instrumental music of all shapes and sizes, from solo keyboard to music for winds. Haydn used the term for keyboard sonatas, trios and quartets for string trios, quartets and octets, and for music for wind band. Frequently, the divertimento indicates music in a lighter, entertaining vein, something to ‘please the ear,’ as one writer puts it at the turn of the 18th century. The divertimento is generally less intricate than a sonata, symphony or concerto. On occasion, it was played as background music or as social music for a person’s name day, as with Mozart’s two Divertimentos K. 247 and K. 287 for Countess Lodron, written for his favored combination of two horns and strings. These and other divertimentos by Mozart were generally written in his earlier years in Salzburg. In Vienna, by the last two decades of the 18th century, Mozart found that the term was falling out of use in favor of the specific terms quartet, quintet or symphony preferred by music publishers.

For much of 18th century Austria, the divertimento was something of a catch-all term for instrumental music of all shapes and sizes, from solo keyboard to music for winds. Haydn used the term for keyboard sonatas, trios and quartets for string trios, quartets and octets, and for music for wind band. Frequently, the divertimento indicates music in a lighter, entertaining vein, something to ‘please the ear,’ as one writer puts it at the turn of the 18th century. The divertimento is generally less intricate than a sonata, symphony or concerto. On occasion, it was played as background music or as social music for a person’s name day, as with Mozart’s two Divertimentos K. 247 and K. 287 for Countess Lodron, written for his favored combination of two horns and strings. These and other divertimentos by Mozart were generally written in his earlier years in Salzburg. In Vienna, by the last two decades of the 18th century, Mozart found that the term was falling out of use in favor of the specific terms quartet, quintet or symphony preferred by music publishers.

Mozart’s Divertimento in E-flat major, K. 563, however, is the exception that proves the rule. It is Mozart’s only full-scale trio for violin, viola and cello and it ranks with the absolute best. It is a late work, dating from 1788, and its modest title – Mozart had not used the term ‘divertimento’ for more than a decade – offers little preview of the ambition and scale of the music that is to follow. K. 563 is Mozart’s longest chamber work and marks the summation of the 18th century Austrian divertimento. It represents the very pinnacle of writing for string trio.

— All program notes copyright © 2024 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: khnotes@sympatico.ca