Composed 1861; 49 minutes

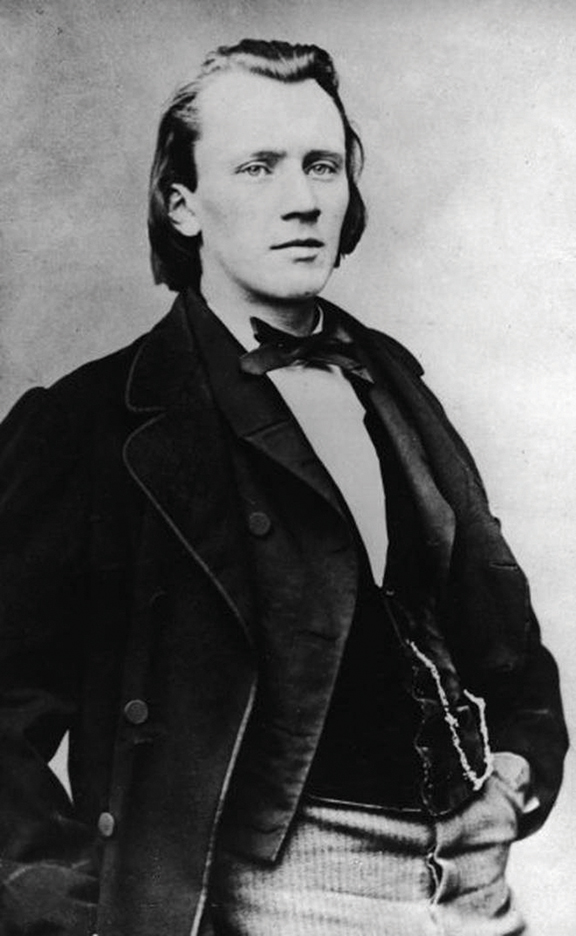

The 29-year-old Brahms was being unusually candid and open in this letter he wrote to Clara Schumann, November 18, 1862. He was feeling bruised and rejected by his home city of Hamburg, passed over for a position conducting its Sing-Akademie. He wrote the letter from Vienna where he had just arrived for a short visit, his first visit to a city whose musical history he venerated. Remarkably, just days after the biggest disappointment of his life, he was to have the greatest success in the first three decades of that life. The recently completed music he took with him to Vienna, which includes this evening’s A major Piano Quartet, Op. 26, its immediate predecessor, in G minor, and the Handel Variations, was to provide the passport to this success.

He performed today’s piano quartet in his début concert for the prestigious Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Friends of Music) on November 29, 1862. The next day, bundling all the reviews into a package, he wrote to his parents back in Hamburg: “Yesterday brought me great joy; my concert went quite splendidly, much better than I had hoped.” One of the clippings Brahms sent included a review by Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, who had built a reputation for being notoriously parsimonious with praise, particularly for anything that might appear to challenge tradition. In it, Hanslick described the young musician from Hamburg as “possibly the most interesting among our contemporary composers.”

“One wants to have ties and a livelihood that turns living into a life. One is afraid of loneliness. Activity in lively union with others and lively social relations, family happiness – what human being doesn’t feel the longing for that?”

Both piano quartets had already been informally welcomed when Brahms played them with the Hellmesberger Quartet at the home of Julius Epstein, a piano professor at the Conservatoire. Violinist Joseph Hellmesberger echoed Schumann’s famous words when he proclaimed: “This is indeed Beethoven’s heir.” Brahms extended his planned visit to Vienna from a few weeks to a residence for the rest of his life. On the rebound of his rejection by one city, he had found the life he longed for in another.

The radiant A major piano quartet contrasts with the gravity and intensity of the G minor. Its four movements are full of characteristic turns of a phrase, distinctive rhythms and structures that recur throughout Brahms’s music. In the sunny opening theme of the work, for example, there’s a fascination with the rhythmic interplay of groups of two and three notes – the hemiola effects found in works as far apart as the early piano sonatas and the late clarinet sonatas. The expansiveness of the music (this is the longest of Brahms’s chamber works) suggests Schubert, a composer whom both Brahms and the city of Vienna had begun to discover and appreciate in the years preceding its composition. The nocturnal Poco Adagio, beginning and ending with muted strings, is a broadly drawn ternary structure and one of Brahms’s most deeply personal utterances. With its gentle, sinuous opening theme, the scherzo creeps in more like a lamb than a lion, though its canonic trio section adds a mild roar. The exuberant finale is rich in themes, with a distinctive Hungarian feel to the first of them, and a spacious, leisurely sonata-rondo structure which concludes on an almost symphonic scale.

— All program notes copyright © 2024 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: khnotes@sympatico.ca