Written by Anna Vorhes

Born

December 22, 1803, La Côte-Saint André, Isère, France

Died

March 8, 1869, Paris, France

Instrumentation

two flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), two oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets (2nd doubling E flat clarinet), four bassoons, four horns, two trumpets and two cornets, three trombones, two ophicleides (often replaced by bass tubas), timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, bells, two harps and strings

Duration

49 minutes

Composed

1830-32 with later revisions

World Premiere

December 5, 1830 in Paris. A revised version was presented in Paris on December 9, 1832, which is often considered the premiere date

Something interesting to listen for

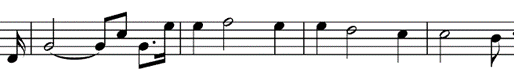

The most well-known characteristic of this symphony is the melody that recurs in every movement. The melody is a depiction of Irish actress Harriet Smithson, a Shakespearian specialist who dazzled Berlioz with her depiction of Ophelia in Hamlet in 1827. The composer and the actress didn't meet at the time, and Berlioz won the Prix de Rome, requiring him to study in Rome for two years. His interest in and obsession with Smithson led him to compose Symphonie fantastique, using a single melody to depict her. Here's the beginning of the phrase:

This melody Berlioz calls the idée fixe, a fixed idea or obsession. Berlioz and French author Honore de Balzac coined the term about the same time, and it was used widely in literature as well as music before it became a psychological term. This melody occurs throughout the symphony but transforms as the story progresses. From sweet and intriguing, it moves through various characteristics to become the cry of a witch in the final movement. In the final movement you will hear not only the idée fixe but also the unearthly shrieks of the witches created by the strings using the wood rather than the hair of their bows, the striking of church bells and the brass offering the Gregorian chant depicting the wrath of God, the Dies irae.

Interestingly, Berlioz managed to provide a ticket for Smithson to attend the premiere in 1832, and they met and married shortly thereafter. Unfortunately, the marriage was not happy, though Berlioz cared for Smithson for the rest of her life, even installing her in a lovely dwelling after she had a stroke which left her paralyzed. They were divorced by then, but Berlioz visited her almost daily when he was in Paris and provided for her care.

Program Notes

This symphony is considered the most audacious of first symphonies to ever have been created. Far from following in his predecessors' footsteps, Berlioz went a completely new route. Perhaps this was caused by the fact that the composer could not play piano. His father wanted him to become a physician, and when Berlioz was too intrigued by making music as a child, the father disposed of the piano in the household so his son wouldn't be distracted. Berlioz managed to learn to play the guitar, and later picked up the flute, but he didn't have the basic training most composers begin with. He studied the instruments of the orchestra academically and wasn't afraid to ask them to play in new and different ways. Berlioz' book on orchestration is still considered a good reference today, though a bit outdated.

To understand the Symphonie fantastique, it's important to understand Paris of the early to mid-nineteenth century. Drugs were part of the culture, especially opium. There were commercial establishments that catered to those who wished to experience the drug. These opium dens ranged from opulent and expensive to hovels. The preferred method for ingestion was often vaporizing the drug. Laudanum (opium dissolved in alcohol) was a household pain reliever. When Berlioz writes of being a opium eater, he was describing something both legal and common in the Paris of his day. The entire Symphonie fantastique is described by the composer as an opium dream.

Before the program of the symphony is presented, let's look at the production of the premiere and the revisions. In his autobiography, the composer tries to explain the first attempted performance. In a world where most symphonies required 40-60 players (Beethoven's Ninth Symphony being an exception), Berlioz hoped for well over 100. The stage manager couldn't conceive of that number, and even with Berlioz and his organizer trying to explain what was needed, the production was abandoned before the first rehearsal. The musicians did read some of the music, reacting well to the fourth movement, March to the Scaffold.

In 1830 a performance was mounted that was more successful. The title sheet described a symphony in four movements, which was then crossed out and replaced with five. Un bal, now the second movement, occurred as the third movement, the traditional place for a dance movement. By the 1832 premiere, the movements had been moved to their current order. The symphony would be revised further, and at one point, Berlioz even wrote a work to follow the Symphonie fantastique. Berlioz led performances of the Symphonie fantastique many, many times throughout his international career.

On the first performance, the composer distributed a program indicating his story depicted in the composition. Here are excerpts of that program:

Program of the Symphony: A young musician of unhealthy sensibility and passionate imagination poisons himself in a fit of lovesick despair. Too weak to kill him, the dose of the drug plunges him into a heavy sleep attended by the strangest visions, during which his sensations, emotions, and memories are transformed in his diseased mind into musical thoughts and images. Even the woman he loves becomes a melody to him, an idée fixe, so to speak, that he finds and hears everywhere.

Movement One: First he recalls the soul-sickness, the aimless passions, the baseless depressions and elations that he felt before first seeing his loved one; then the volcanic love that she instantly inspired in him, his jealous furies; his return to tenderness; his religious consolations.

Movement Two: He encounters his beloved at a ball, in the midst of a noisy, brilliant party.

Movement Three: He hears two shepherds piping in dialogue. The pastoral duet, the location, the light rustling of trees stirred gently by the wind, some newly conceived grounds for hope - all this gives him a feeling of unaccustomed calm. But she appears again...what if she is deceiving him?

Movement Four: He dreams he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned to death and led to execution. A march accompanies the procession, now gloomy and wild, now brilliant and grand. Finally the idée fixe appears for a moment, to be cut off by the fall of the ax.

Movement Five: He finds himself at a Witches' Sabbath...Unearthly sounds, groans, shrieks of laughter, distant cries echoed by other cries. The beloved's melody is heard, but it has lost its character of nobility and timidity. It is she who comes to the Sabbath! After her arrival, a roar of joy. She joins in the devilish orgies. A funeral knell, burlesque of Dies irae.