DURATION: About 14 minutes

INSTRUMENTATION: harpsichord solo, two violins, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

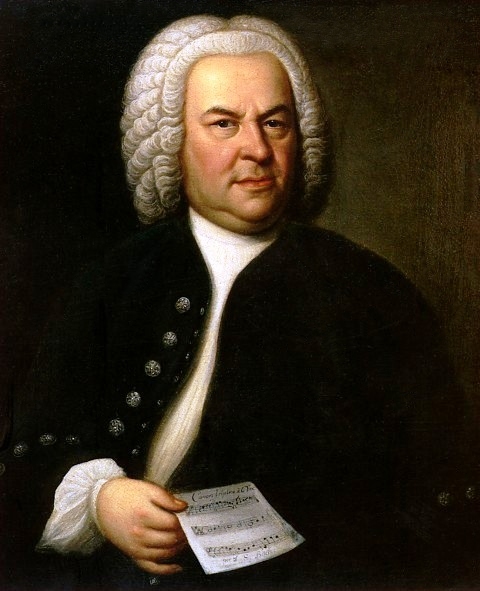

“It’s easy to play any musical instrument: all you have to do is touch the right key at the right time and the instrument will play itself.”--Johann Sebastian Bach

CONCERTO: A composition that features one or more “solo” instruments with orchestral accompaniment. The form of the concerto has developed and evolved over the course of music history.

FURTHER LISTENING:

Keyboard Concerto No. 2 in E Major

Keyboard Concerto No. 3 in D Major

Keyboard Concerto No. 6 in F Major

Even the most creative of musical geniuses need to refuel on occasion. For some composers, this meant walks in the countryside. For others, seaside stays to restore spirits and health. Johann Sebastian Bach wasn’t much for vacations, but he loved coffee, to the tune of about 30 cups a day during periods of intense work. (It’s a vice he shared with Beethoven, actually.)

He wasn’t alone—Europe’s collective need for a caffeine hit in the 18th century had given rise to a wave of coffeehouses across the continent, including in Bach’s home city of Leipzig. And it was at one such house, Zimmermann’s, that Bach hosted regular concerts from 1720 until his death, premiering many of his newer works on Friday afternoons, manically fueled by the dark bean.

Whether the Keyboard Concerto No. 4 actually premiered there isn’t known, but it’s certainly plausible. Bach’s later harpsichord concertos—including the one at hand—were generally arrangements of previously written concertos for other instruments. (The harpsichord, a precursor to the piano, was more commonly an accompaniment instrument—Bach himself is responsible for pushing it into the spotlight.)Scholars believe this particular concerto may have once been a concerto for a kind of oboe, given the exceptionally lyrical melodies for the soloist, but again, it’s not known for certain.

What is certain is that the music sparkles from its first notes, launching with a sprightly allegro that glistens with wit and charm. Baroque music is exceptionally formal, and Bach wrings emotion and nuance from a very limited toolbox of melodic ideas. These snippets are transposed and transformed and elongated and truncated, but they are typically recognizable to the ear, giving the movement a sense of cohesion.

Next, the slower Larghetto movement, a lamentation befitting a tragic opera. It is sparsely textured and features achingly lyrical lines in the soloist’s right hand. It is the emotional center of the concerto, and it stands in sharp contrast to the outer movements. Indeed, the finale steps lively with purpose. It isn’t breakneck fast. Instead, Bach heavily ornaments elegant lines with whizzing scales and decorative trills, gilding a simple dance tune with decorations fit for a king.