INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, suspended cymbal, harp, strings, and solo violin.

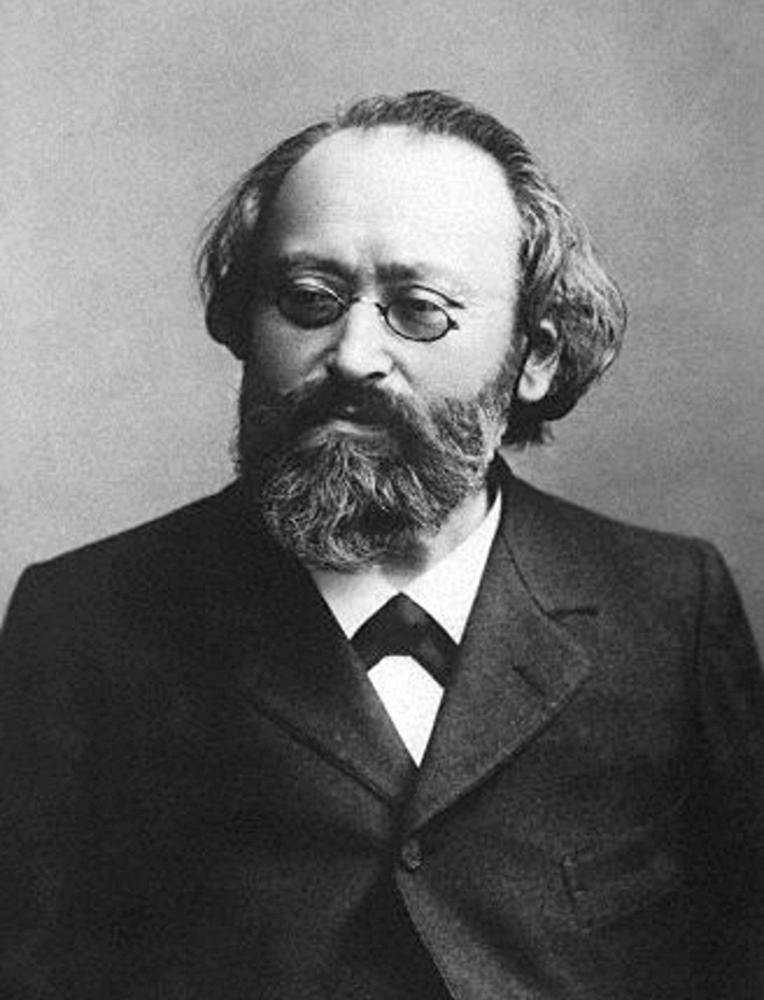

“The violin can sing a melody better than the piano can, and melody is the soul of music.” — Max Bruch

FANTASY: A composition that doesn’t adhere to strict forms like sonata form and that often features a “solo” instrument and quasi-improvisatory passages.

FURTHER LISTENING: Bruch: Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26; Kol Nidrei for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 47 It takes two to tango, and two to compose a great concerto. Composers wrote many of their greatest works for solo instruments and orchestra for and with a respected friend and collaborator.

Take Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy: though Bruch dedicated the piece to the famous violinist Pablo de Sarasate, it was another violinist, Joseph Joachim, who assisted Bruch with some technical advice on the piece and who gave the premiere with the composer himself conducting the orchestra. Despite the pair’s long history — Joachim had advised Bruch on the latter’s earlier violin concerto and other works — Bruch was furious after the premiere and claimed that Joachim’s performance was “careless, lacked modesty, nervous, and lacked insufficient technique. The clown ruined it!”

Ouch.

(Other great composers including Brahms, Dvořák and Schumann had also written concertos for Joachim and found him quite difficult to work with. History is riddled with snarking composers and collaborating soloists.)

Regardless of the spats of artists, the work itself is an often-performed gem. Bruch explains the title himself: “The title ‘Fantasy’ is very general, and as a rule refers to a short piece rather than to one in several movements (all of which, moreover, are fully worked out and developed). However, this work cannot properly be called a concerto because the form of the whole is so completely free and because folk melodies are used.”

Bruch was born to a wealthy German family and displayed early musical talent. His Scottish Fantasy draws its melodies from four Scottish folk melodies, all the rage at the time. The opening movement begins with a noble lamentation in the brass before the violin begins singing an embellished version of the tune “Through the Wood Laddie” slowly, plaintively, over simple orchestral chords. (Bruch referred to this opening as “an old bard contemplating a ruined castle, and lamenting the glorious times of old” — and his heavy use of the harp does indeed give the movement a certain troubadorish flavor.)

The second movement is a lighthearted, quick-stepping take on an 18th century dancing tune, “The Dusty Miller.” The third movement adagio is adapated from the tune “I’m a’Doun for Lack O’Johnnie,” a sweet, nostalgic strain. Finally, the Fantasy ends with the triumphant melody “Hey Tuttie Tatie,” used in the patriotic anthem “Scots wha Hae.” Robert Burns, the great Scottish poet, set the following text to this rousing song:

Scots, wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,

Scots, wham Bruce has aften led;

Welcome to your gory bed,

Or to victory!

(C) Jeremy Reynolds