INSTRUMENTATION: Three flutes and piccolo, two oboes and English horn, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, two harps, and strings.

SYMPHONY: An elaborate orchestral composition typically broken into contrasting movements, at least one of which is in sonata form.

FURTHER LISTENING:

Elgar: Symphony No. 2 in E-flat Major; Variations on an Original Theme (“Enigma Variations”); Elegy

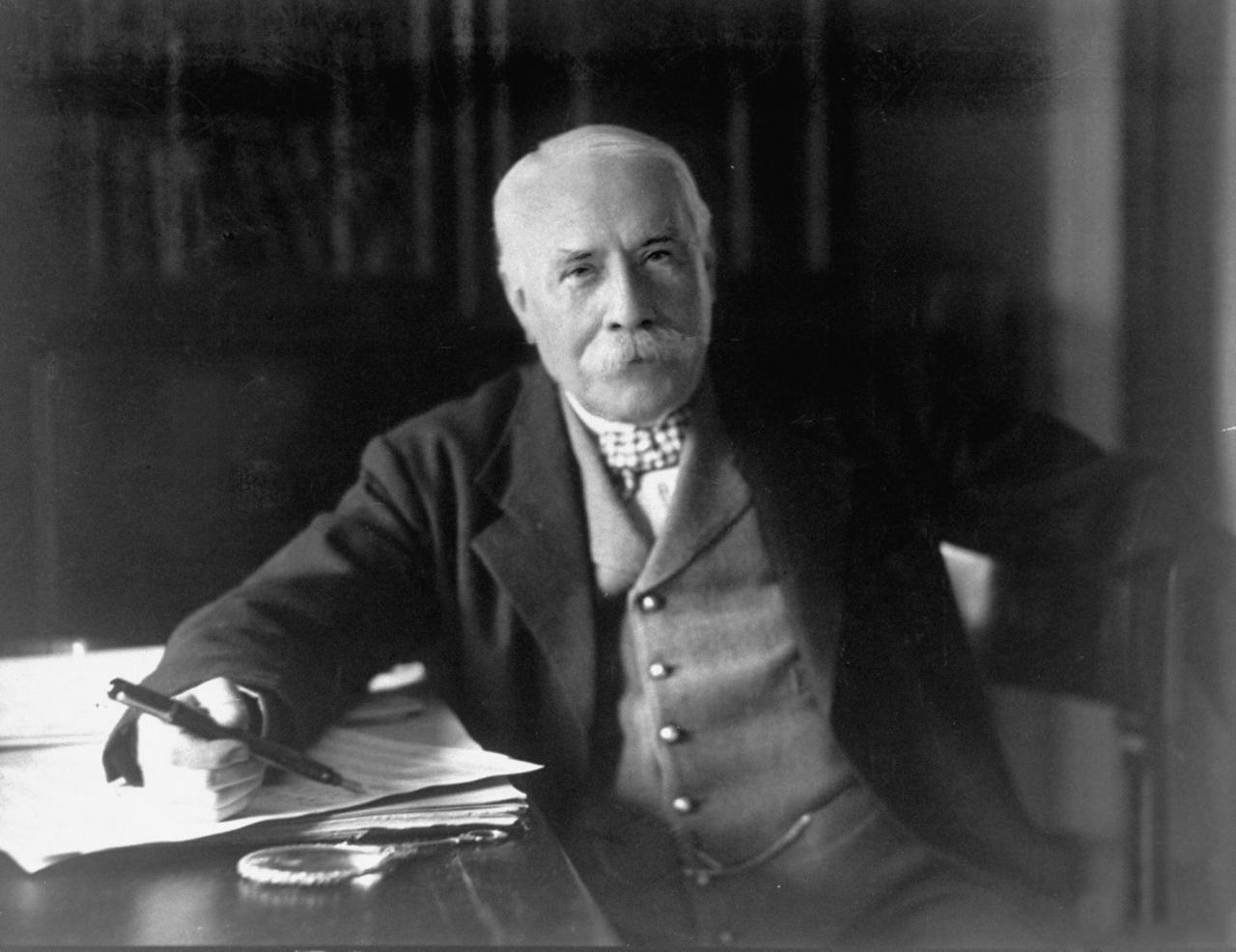

The English composer Edward Elgar belongs to a rather select club: He was knighted by his Queen in 1904 in recognition of his outstanding contributions to British music. While other European nations had developed an extensive cannon of works built from folk music or national themes, Britain often imported composers from Germany or Italy rather than cultivating its own.

Elgar, an avid bicyclist and the son of a piano tuner of modest means, toiled diligently to change that reality. Though he loathed English folk music and refused to build his music from such “museum pieces,” as he called them, his particular blend of other nations’ stylings helped to create a new and uniquely British sort of music, a curious assimilation of French and German traditions.

The first of his two symphonies is a grand, cyclic work in that the opening melody returns at the close of the final movement to help tie the entire work together. For many years, Elgar had been intimidated by the thought of composing a symphony, as he believed a symphony to be the “highest development of art.” It was after the success of his still-revered “Enigma Variations” that he decided to embark on an abstract symphony, a sharp about-face from the detailed program of each “Enigma” variation representing a particular friend or loved one.

The symphony’s opening movement unfurls slowly, a calm, trudging bass line stepping underneath long melodic lines. “The opening theme is intended to be simple and, in intention, noble and elevating,” Elgar wrote, continuing: “the sort of ideal call — in the sense of persuasion, not coercion or command — and something above everyday and sordid things.” A faster second theme retains the heavy footfalls in the bass line but speeds up the melodic line considerably. These themes alternate and blend and transform throughout the movement.

The second movement is zippy and quick, all fluttering nervous energy, though it, too, maintains a walking base at times. There is a lyrical middle section for contrast, and at the movement’s close, the fast first theme slows and transforms into the slow melody of the Adagio movement, another example of the work’s coherence.

To close, Elgar recycles material from the first movement, first in a dark, portentous introduction and later in a glorious restatement of the symphony’s opening theme at the climax. He firmly believed that symphonies should stand on their own, divorced of a programmatic context, and his only note for this symphony reads as follows: “There is no program beyond a wide experience of human life with a great charity (love) and a massive hope in the future.”

(c) 2024 Jeremy Reynolds