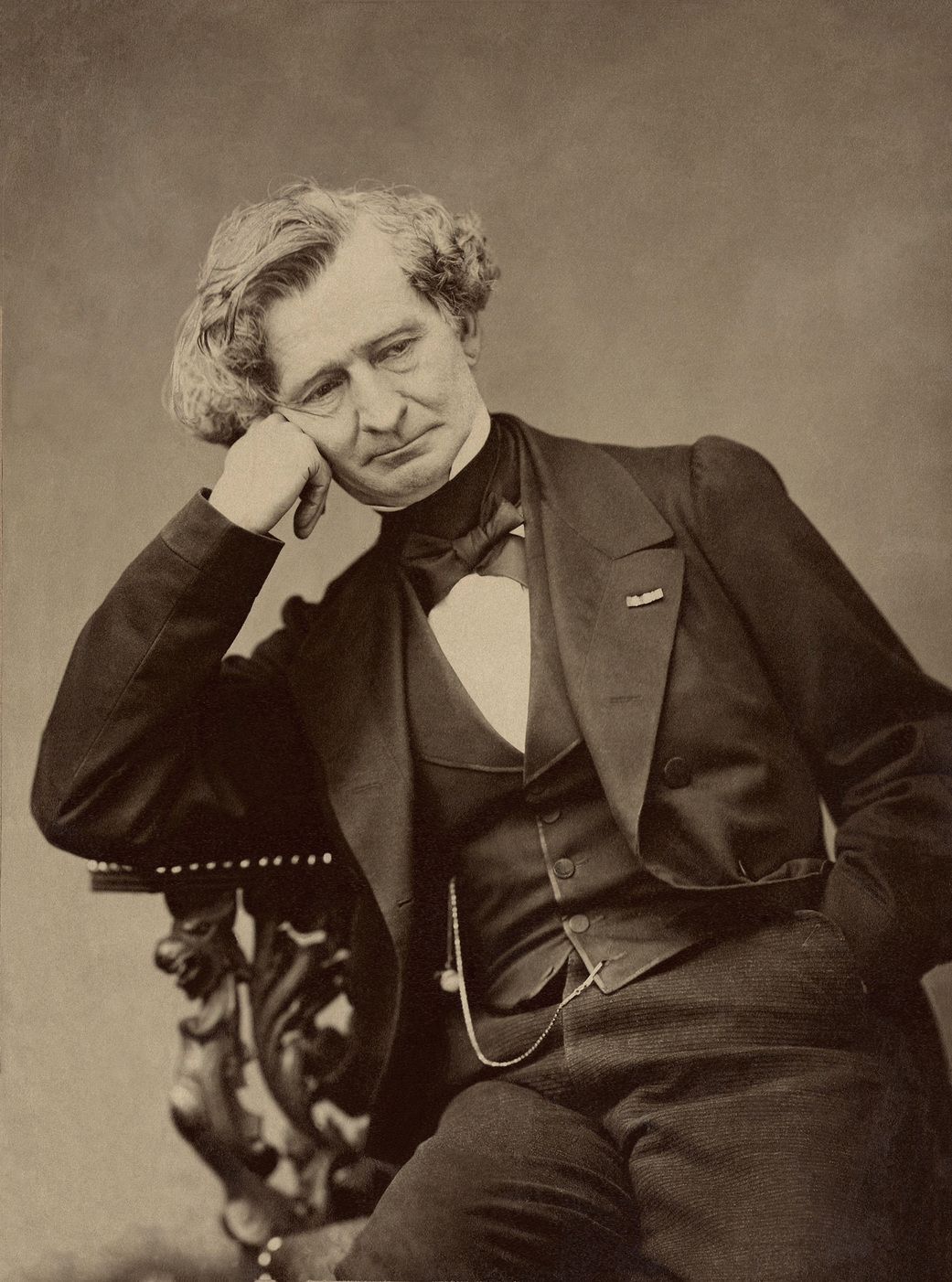

“I would spend days on the banks of the Arno, in a delightful wood over a mile away from Florence, reading Shakespeare. That is where I read for the first time King Lear, and I screamed with admiration for this work of genius; I thought I would suffocate in my enthusiasm, and rolled around (in the grass, admittedly), but I did roll around convulsively to give vent to my excitement.”— Hector Berlioz

OVERTURE: An introduction to a large dramatic work, such as a ballet or opera, that demands listeners’ ears and sets the tone of the evening. Alternatively, these can be standalone concert works written on a subject or theme.

FURTHER LISTENING:

Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini

Le Corsaire, Overture

Waverly, Grand Overture

French composer Hector Berlioz once plotted to murder his ex-fiancé.

A passionate, tempestuous man, the composer flew into a rage in 1830 when he learned that his future mother-in-law had pushed her daughter to break off her engagement to Berlioz and instead marry a wealthy piano manufacturer. Berlioz dreamed up an elaborate plot involving cross-dressing, poison, and pistols to kill both his former fiancé, a young pianist, and her mother, who he called “l'hippopotame.” (Yes, he called her “the hippopotamus” in public. Seriously.)

Berlioz discussed his plan in great detail in his memoirs. What stopped him from committing the deed? In a word: Shakespeare. He had first encountered the Bard in 1827, writing: “Shakespeare coming upon me unawares struck me like a thunderbolt.”

In his pain, he turned to the Bard’s words for comfort and found fresh inspiration. He abandoned his cartoonish murder plot and instead wrote the King Lear Overture, based on the Shakespeare tragedy about a king seeking to divide his realm among his three daughters. In the play, two of the daughters flatter the king to win more of the kingdom while the third — Cordelia, the heroine — refuses to attempt to prove her love for her father. Lear disowns the third and descends into madness.

Berlioz’s musical retelling of the tale begins with a fierce but unstable proclamation from the king in the low strings. This is the first theme. The second begins with a plaintive oboe simple, contrastingly lyrical and sweet — this is Cordelia’s music. The remainder of the overture loosely sketches the action in Shakespeare’s tragedy, eschewing traditional sonata form for a more free-flowing, rhapsodic style.

The composer himself provides the following insight:

It used to be the practice at the French court, as late as 1830 under Charles X, to announce the king’s entrance to his chambers (after Sunday mass) with the sound of a huge drum which beat a strange rhythm of five beats; this was a tradition handed down from very ancient times. This gave me the idea of accompanying Lear’s entrance to his council chamber for the scene where he divides his states with a similar figure on the timpani. As for the king’s madness, I only intended to portray it towards the middle of the allegro when the lower strings take up the theme of the introduction during the storm. To perform this overture you need a first-rate orchestra; I have not heard it since my last trip to Hanover; it is the King’s favorite piece.

Later, in 1833, Berlioz married Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, the inspiration for his most famous work, the Symphonie Fantastique.