Alex Klein, oboe

Michael Partington & Yaniv Attar, guitar

Dawn Posey, Shu-Hsin Ko, Yuko Watanabe, & Heather Ray, violin

November 20, 2021 @ 7:30 PM

November 21, 2021 @ 3:00 PM

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

CONTRAPUNCTUS NO. 1 AND NO. 4 "THE ART OF THE FUGUE," BWV 1080 (7')*

Roberto Sierra (1953-)

FANTASÍA CORELLIANA (13')

I. Grave

II. Presto

III. Vivace

IV. Presto

- featuring Michael Partington & Yaniv Attar on guitar

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

CONCERTO FOR FOUR VIOLINS IN B MINOR, OP. 3, NO. 10, RV 580 (11')

I. Andante

II. Allegro assai

III. Adagio

IV. Allegro

- featuring Concertmaster Dawn Posey, Assistant Concertmaster Shu-Hsin Ko, Principal 2nd Violin Yuko Watanabe, & Assistant Principal 2nd Violin Heather Ray on violin

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704)

BATTALIA À 10 (9')

I. Sonata

II. Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor

III. Presto

IV. Der Mars

V. Presto

VI. Aria

VII. Die Schlacht

VIII. Adagio. Lamento der Verwundten Musquetirer

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Alex Klein, Trans. (1964-)

E MAJOR VIOLIN CONCERTO TRANSCRIBED FOR OBOE IN F MAJOR, BWV 1042 (16')

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Allegro assai

- featuring Alex Klein on oboe

*Parts available by the Australian Chamber Orchestra

Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel’s informative and engaging Pre Concert Lecture about the program will air in the week before our concert, on the BSO website here.

- Bach’s monumental Art of Fugue culminates in a set of mirror fugues that are played both upside-down and right-side-up!

- Vivaldi’s B-minor Concerto for Four Violins enjoyed a second life as one of Bach’s harpsichord concertos.

- The early English music historian Charles Burney wrote of Heinrich Biber, “of all the violin players of the last century Biber seems to have been the best, and his solos are the most difficult and most fanciful of any music I have seen of the same period.”

- Roberto Sierra uses the term “tropicalization” to describe his fusion of European modernist styles with Latin American folk traditions.

PROGRAM NOTES

In many ways, the Baroque era (spanning roughly 1600-1750) can be viewed as the center-point in the history of Western music. It is the period that witnessed the birth of tonality—the practice of beginning in one key, leaving for another, then returning again—which became the foundation of nearly all music that followed. Preceding the Baroque is the Renaissance and the music of antiquity; from it emerged the first tender shoots of Modernity. If the Baroque is at the midpoint of music history, then Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) is at the center of the Baroque. It is impossible to overstate his influence, which impacted everything from basic principles of voice-leading to the method by which keyboard instruments are tuned. Feared and revered in equal measure by performers, Bach’s unique voice is immediately identifiable, and his vast oeuvre spans the genres of keyboard music; solo sonatas; over 200 sacred and secular cantatas; massive oratorios; concertos for a variety of instruments; and a precious handful of orchestral masterworks.

Among Bach’s lifelong passions was the musical canon, a game-like compositional technique in which one or more themes are layered upon themselves according to pre-established rules. The simplest and most familiar kind of canon is the round—think Frère Jacques or Row, Row, Row Your Boat—in which each performer begins the tune at a precise interval of time after the previous entrance. Canons come in all shapes and sizes, and Bach relished in his singular ability to compose them with both fluency and style under even the most rigorous and convoluted rulesets. His canonic apotheosis was the Musical Offering, a collection of canons notated as musical puzzles and presented as a tribute to Frederick the Great of Prussia in 1747 (and all based on a serpentine theme supplied by the monarch himself).

The species of canon most closely associated with Bach is of course the fugue, a form in which each repetition of the theme—or themes—appears in a new key and can be subject to any number of other permutations as well. Bach’s catalogue includes hundreds of fugues for forces ranging from organ to chorus to solo violin. And even in the 1730s and 1740s, as musical tastes were shifting away from the densely cerebral counterpoint for which Bach was famous (later critics referred to it as the “learned” style), the composer continued to push the boundaries of the fugue in ever more complicated directions. Bach’s magnum opus in this field is his Art of the Fugue, completed in stages over the final decade of his life. Like the Musical Offering, the work is a compilation of many smaller compositions, in this case thirteen fugues (and an incomplete fourteenth) and four canons. The fugues are arranged in progressive order of complexity, from relatively straightforward single-subject exercises in four voices to mind-boggling mirror fugues in which the entire piece is flipped upside down but completely maintains its musical integrity.

Impressive as they are, canons and fugues only represent one corner of Bach’s prolific output. He was also a leading voice in the emerging genre of the concerto, and wrote many for both solo and multiple instruments. Like most composers of his time, Bach frequently recast his pieces for different—sometimes drastically different—settings. His Concerto for Two Harpsichords (BWV 1060), for example, had its origins as feature for oboe and violin. Though it may raise the eyebrows of our modern sensibilities, given the plasticity of Bach’s settings, it is fully in keeping with Baroque practice that this weekend’s programs include Bach’s E Major Violin Concerto performed on the oboe (and transposed up a semitone to the much more oboe-friendly key of F Major).

Baroque composers did not necessarily limit themselves to their own works when creating these new arrangements of older pieces. Another of Bach’s Double Harpsichord Concertos (BWV 1064 in B minor) is a rewrite of the Concerto for Four Violins (Op. 3, No. 10) by his Italian counterpart Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741). Bach had become acquainted with Vivaldi’s music around 1712-13, while working for the court at Weimar. The young Prince Johann Ernst, stepbrother of Bach’s employer, was a passionate amateur musician, and had brought a copy of Vivaldi’s first series of concertos—L’estro armonico, Op. 3—home with him after several years spent studying abroad in the Netherlands. Bach gleaned a great deal from studying Vivaldi, particularly with regards to concerto form (the Italian was a pioneer of the fast-slow-fast three-movement structure), and transcribed a number of his pieces for organ and harpsichord. We also hear the influence of Vivaldi’s supple melodic writing and orchestral techniques in Bach’s own compositions from that point forward. Though his music might not approach the divine profundity of Bach, Vivaldi’s crystalline textures, regular phrase lengths, and carefully structured changes of key represent a prescient anticipation of the direction popular musical tastes would drift later in the century.

Though his life overlapped with those of both Bach and Vivaldi, the music of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704) is more connected to the freewheeling dramatic style of Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) and other earlier composers than to the structure and refinement of the mature Baroque. Like Vivaldi, Biber was a masterful violinist as well as a composer, and his pieces routinely feature unusual string tunings, percussive effects, and other techniques that fully capitalize on the full sonic range of the violin and its cousins in the string orchestra.

Biber’s 1673 suite Battalia appears as something of a curiosity in our time, but actually is among the most famous surviving examples of a genre of “battle music” that was popular throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Most battle pieces were not intended to be played during actual combat (as is the case with true military music), but rather served to commemorate important victories, evoke the atmosphere of war in operas and ballets, or represent conflict in a more general sense. Some notable later descendants of this music include Beethoven’s “Battle Symphony,” Wellington’s Victory (1813) and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture (1880), both of which enjoyed fervid public acclaim but were not particularly favored by their composers.

Throughout the eight short movements of Biber’s Battalia, we hear the cacophony of drunken soldiers singing together (perhaps “simultaneously” is a more accurate descriptor) in a multiplicity of keys, the double bass mimicking a snare drum by inserting a piece of paper against its fingerboard, and the snapping of strings in imitation of gunfire. Most striking (and strikingly modern) is the piece’s finale (“Lamento der Verwundten Musquetirer;” “Lament of the Wounded Musketeer”), which concludes not with victory, but with heartbreaking regret.

The outlier in this program is Roberto Sierra (b. 1953). Born in Puerto Rico, Sierra studied in Hamburg with the avant-garde icon György Ligeti, and has taught in the United States at Cornell since 1992. Most of his music is for instrumental forces, and can be found on programs by top-level orchestras and chamber musicians internationally. Sierra’s voice is a fusion of abstract modernism and Latin American folk and popular music. He often draws on much older sources of musical raw materials as well. In his Fantasía Corelliana for two guitars and string orchestra, Sierra leans heavily on the work of Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713), one of the most influential figures in the development of Baroque and early Classical style. Sierra’s uncanny imitation of Corelli is spattered throughout with modern touches of rhythm, harmony, and color, resulting in a thoroughly charming pastiche of old and new.

Copyright © 2021 Ryan Dudenbostel

Ryan Dudenbostel is the Director of Orchestral Studies at Western Washington University, where he conducts the WWU Symphony Orchestra, coordinates the graduate program, and directs the contemporary music ensemble NowHearThis! Previously, he was Music Director of the El-Sistema-based Santa Monica Youth Orchestra in Los Angeles. He recently served as Interim Artistic Director of the Marrowstone Music Festival, and regularly returns to LA for concerts with the Jacaranda new music series.

![]()

Program notes sponsored by: First Federal

We are so grateful for our generous sponsors!

Season: Peoples Bank & Bellingham Porsche/Audi

Concert: The Willows

Guest Artists: Barron Smith Daugert & Lesli Beasley, Windermere Senior Real Estate Specialist

Pre Concert Lecture: Barkley Village

Program Notes: First Federal

For a full list of BSO's sponsors, please visit our website sponsor page.

Chamber orchestra musicians performing in this concert are in bold.

Music Director

Yaniv Attar (bio)

The Jack & Marybeth Campbell Music Director

Violin I

Dawn Posey (bio)

The Garland Richmond & Richard Stattelman Concertmaster

Shu-Hsin Ko

Assistant Concertmaster

Emily Bailey

Laura Barnes

David Bean*

Gaye Davis

Joanne Donnellan

Irene Fadden *

Matt Gudakov

Madeline Massey

Yelena Nelson

Sandra Payton *

Krissy Snyder

John Tilley

Karen Visser

Bill Watts

Violin II

Yuko Watanabe

The Debbie & Steve Adelstein Principal 2nd Violin

Heather Ray

Assistant Principal 2nd Violin

Linnea Arntson

Liza Beshara

Judy Diamond

Kathy Diaz

Geneva Faulkner

Ben Morgan

Lenelle Morse

Audrey Negro

Cecile Pendleton

Carla Rutschman

Tara Kaiyala Weaver

Joy Westermann

Viola

Morgan Schwab

The Byron & Becky Elmendorf Principal Viola

Michael Neville

(Acting Assistant Principal Viola)

Kacey Bradt

Jo Anne Dudley

Natalie Louia

Valerie McWhorter

Jim Quist

Corey Welch

Cello

Nick Strobel

The Phyllis Allport Principal Cello

Tallie Jones

The John W. Tilley Jr. Assistant Principal Cello

Brian Coyne

Erin Esses Lusk

Noel Evans

Omar Firestone

Jeremy Heaven

Rebekah Hood-Sava

Barb Hunter

Coral Marchant

Mary Passmore

Bette Ann Schwede

Samantha Sinai

Daniel Watterson

Bass

Mark Tomko

The Charli Daniels Principal Bass

Eirik Haugbro

Assistant Principal Bass (Acting Principal Bass)

Amiko Mantha

(Acting Assistant Principal Bass)

Faye Hong

Anna Jull

Flute

Deborah Arthur

The Marcela Berg & Michael Addison Principal Flute

Gena Mikkelsen

Piccolo

Gena Mikkelsen

The Carol & Dennis Comeau Piccolo

Oboe

Kristen Fairbank

Co-Principal

Gail Ridenour

The Ridenour Family Co-Principal Oboe

Ken Bronstein

English Horn

Ken Bronstein

The Dick & Sherry Nelson English Horn

Clarinet

Erika Block

The Gordon & Rosalie Nast Principal Clarinet

Emily Prestbo

David Kappele

Bassoon

Phillip Thomas

The Brian and Marya Griffin Principal Bassoon

Jackson Stewart-DeBelly

Assistant Principal Bassoon

Terhi Miikki-Broersma

Horn

Brad Bigelow

The George and Crystal Mills Principal Horn

Jack Champagne

Greg Verbarendse

Kristi Kilgore

Trumpet

Karolyn Labes

The Bill & Leslie McRoberts Principal Trumpet

Del Vande Kerk

Steve Sperry

Assistant Principal/3rd Trumpet

Trombone

Phil Heft

The Wendy Bohlke & Brian Hanson Principal Trombone

Brian Thomson

Bass Trombone

Bob Gray

Tuba

Mark Lindenbaum

The Marty & Gail Haines Principal Tuba

Timpani

Stephanie L. Straight

Principal Timpani

Percussion

Kay Reilly

The Valerie McWhorter & Dean Altschuler Co-Principal Percussion

Melanie Sehman

The Barbara & Michael Ryan Co-Principal Percussion

Jamie Ihler

Harp

Jill Whitman

The Cinda & Stuart Zemel Principal Harp

Keyboard

Andrea Rackl

The Sibyl Sanford Principal Keyboard

Mark Davies §

* Chamber Orchestra 2nd Violin

§ Substitute

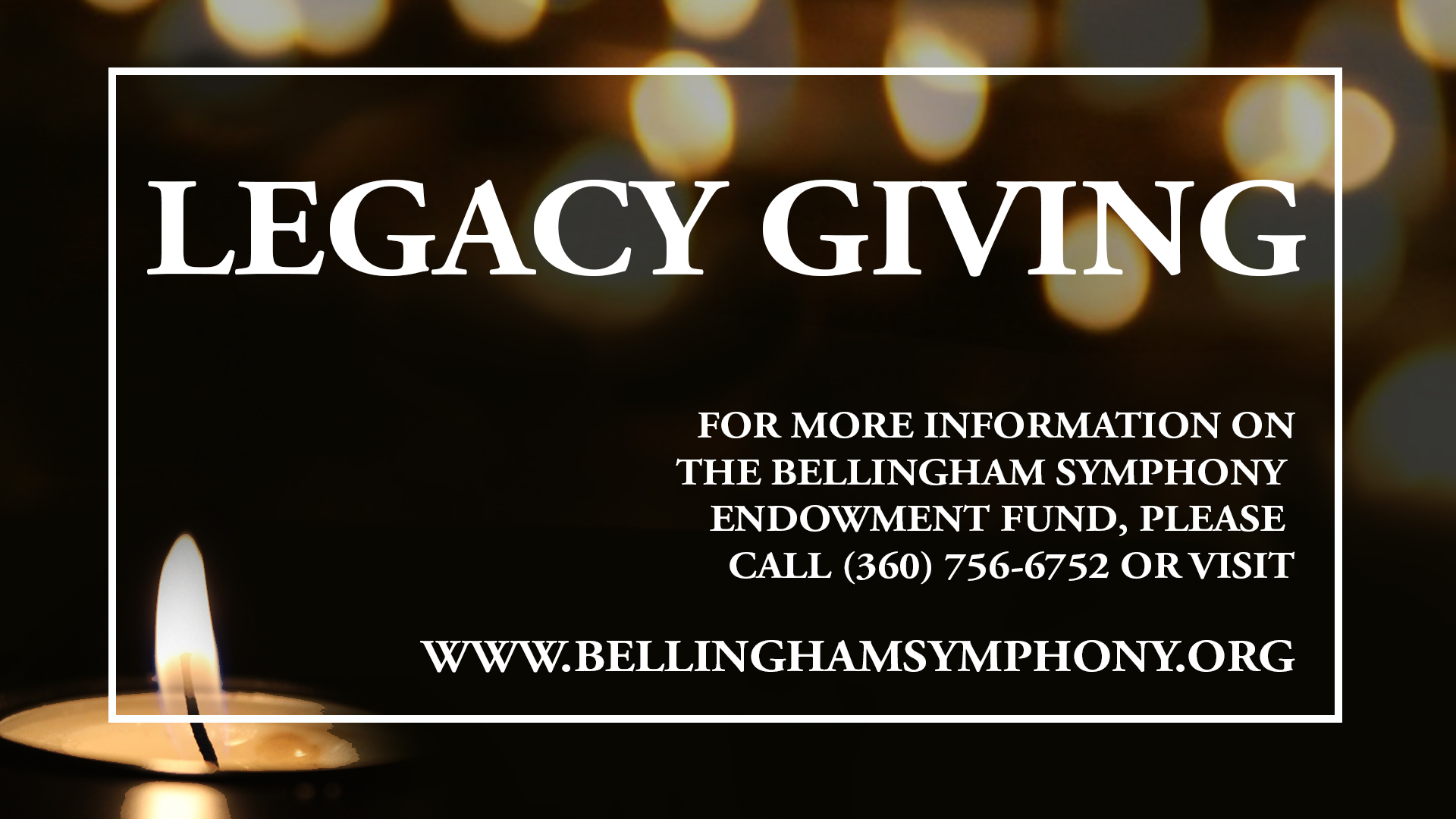

There are many ways to keep the Bellingham Symphony Orchestra’s legacy strong, regardless of your means. We are proud to announce that we now have our own endowment available for legacy giving!

“Our Legacy Society is composed of remarkable, passionate individuals who care deeply about the future of the Symphony and the continuation of our educational programs in the community for years to come.” - Music Director Yaniv Attar

We are so very grateful to our legacy society members, who make it possible for us to keep the music alive, and to encourage musicians of the future. For a list of all our generous contributors and legacy society members, please click here.

For more information, contact us at (360) 756-6752 or by email to executive@bellinghamsymphony.org. You can also see more about ways to give here.

Giving to the BSO

We appreciate our many contributors and donors! Please click here to see our contributors listing for today's program. Thank you for helping the BSO bring the gift of music to our community during these times.

For more information on how to give at a personal level, please click here. If you are interested in information on how to become a Chair Underwriter or Sponsor, please click here.

The Bellingham Symphony Orchestra is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Your contribution is fully tax deductible as provided by law.

.jpeg)