James R. Cassidy, Music Director

7:30 P.M. Saturday, October 31, 2020

Verst Group Logistics,

Hebron, Ky.

James Cassidy, conductor

Geff Strik, artist

“Strings Noir”

Ottorino Respighi

Ancient Airs and Dances, Suite 3

I. Italiana

II. Arie di corte

III. Siciliana

IV. Passacaglia

Arnold Schoenberg

“Verklärte Nacht”

INTERMISSION

Bernard Herrmann

Suite from Psycho

I. Prelude

II. The Murder

III. Finale

Ludwig van Beethoven

“Grosse Fuge”

The KSO is supported by the generosity of the Louise Dieterle Nippert Musical Arts Fund of the Greenacres Foundation and the Louise Taft Semple Foundation.

The KSO is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign.

Greetings, masked and virtual patrons,

Greetings, masked and virtual patrons,

What a year.

Thanks for joining us for tonight’s 29th KSO season opener, albeit in an unconventional venue. (Thanks, Paul.) We hope you’ll stick with us through the season — wherever we wind up — for programs featuring favorite opera arias, the Bach family, Dvořák, and the Rat Pack. The KSO will keep the lights on and the sanitizer handy.

Like most U.S. performing arts groups, the KSO has been deeply affected by the coronavirus pandemic. Last spring, we canceled both our Bourbon Barrel Ball and a scheduled screening of Singin’ in the Rain with the orchestra performing the soundtrack live. For 28 years, though, we have overcome a wide range of challenges, setbacks, and obstacles, and we have never let any challenge silence the music. With a different venue and logistical precautions to ensure our performers’ and patrons’ safety, we found a way to offer our free summer series — in person and streamed online. Last week, we offered education series concerts with distanced musicians together on stage.

Faith and fortitude light the orchestra’s path forward together with respect and responsibility. Music, like every other profession, is essential. So the band plays on.

James R. Cassidy

Music and Executive Director

James R. Cassidy, Music Director

Thomas Consolo, Associate Conductor

First Violins

Manami White, concertmistress

The Gloria Goering Memorial Chair

Stacey Woolley

Jacqueline Kitzmiller

Maggie Niekamp

Jacquie Fennell Dorothy Han

Second Violins

Thomas Consolo, principal

The Katie & Stephen Wolnitzek Chair

Johann Bast

Lauren Greene

Maalik Glover

Evan Hurley

Austin Budiono

Violas

Peter Gorak, acting principal

Scott Schilling

Darryl Manley

Yu-Ting Huang

’Cellos

Tom Guth, principal

Kat Aguiar

Jonathan Lee

Elizabeth Lee

Bass

Chris Roberts, acting principal

Brenton Carter

Ottorino Respighi was born July 9, 1879, in Bologna, Italy. He died in Rome on April 18, 1936.

Music has been synonymous with Italy for centuries, but for most of that time — and particularly through the 19th century — Italian music was synonymous with opera. Donizetti, Bellini, Rossini, Verdi, Puccini, Mascagni: One after another, these giants of theatrical music turned out masterpiece after masterpiece, both dramatic and comedic, and became national celebrities.

Music has been synonymous with Italy for centuries, but for most of that time — and particularly through the 19th century — Italian music was synonymous with opera. Donizetti, Bellini, Rossini, Verdi, Puccini, Mascagni: One after another, these giants of theatrical music turned out masterpiece after masterpiece, both dramatic and comedic, and became national celebrities.

Ottorino Respighi took a different path. That was in part a function of geographical luck. He studied at the Liceo Musicale in his home town of Bologna, where the composition teacher was Giuseppe Martucci, who encouraged his students to help reclaim Italy’s lost prominence in instrumental music. (In a local twist, Martucci’s son later taught at the pre-merger Cincinnati Conservatory of Music.)

As a young man, Respighi lived briefly in St. Petersburg, studied with Rimsky-Korsakov, and played viola in the opera orchestra there. It was an invaluable lesson that taught him what orchestral instruments really could do. Before settling full-time in Italy, Respighi also spent time in Berlin, where Max Bruch and his modernist countryman Feruccio Busoni were teaching.

By 1913, he had moved to Rome and was teaching at the Santa Cecilia conservatory; from 1924 to 1926, he was the school’s director. Though he concentrated on composition, he continued to teach through his life.

His reputation as a composer was secured in 1916 with Fontane di Roma (Fountains of Rome), the first of four large orchestral symphonic poems inspired by the Eternal City. His nostalgic fascination with the past led him not just to places around the city but to its music, too, particularly Gregorian chant. Chant-like motifs appeared as early as the 1920s in his music, and chant became the basis of several large works.

Renaissance music also interested him, and between 1917 and 1931 he made three sets of orchestrations of 16th-century lute pieces, dubbing them Ancient Airs and Dances. Like many Romantic-aesthetic treatments of older music, Respighi’s suites were as much recomposition as orchestration. The movements — there are four in each suite, and they are generally of comparable length — are ordered in a progressions that creates the impression of a symphonic whole (although an impression is all it is). The suites all call for modest-sized ensembles.

Respighi wrote the third suite in 1931, eight years after the second. It would be one of the last works he completed; his health worsened soon after, and he completed no new works after 1933. It is scored austerely, for just strings, and packs an emotional intensity and sadness the others lack.

The first movement splices two galliards, one anonymous, one by Santino Garsi da Parma. The second movement, translated as “Courtly Airs,” is a miniature suite in itself, including parts of six highly contrasting songs by Jean-Baptiste Besard. The melancholy opening and closing quotes “It Is Sad to Be in Love with You.” The Siciliano’s inspiration also is anonymous, although the melody was famous in its day as “La Spagnoletta”.

The finale is an imposing and almost tragic passacaglia that starts with an exclamation of the subject and builds in intensity from there. It’s based on another finale, this one from Ludovico Roncalli’s Harmonic Caprices for Baroque guitar.

Arnold Schoenberg was born Sept. 13, 1874, in Vienna. He died in Los Angeles on July 13, 1951.

In a 1967 magazine article, Leonard Bernstein famously wrote that Gustav Mahler symbolically straddled the year 1900 with one foot planted in the traditions of 19th century Romanticism and the other in the unknown world of the 20th century. With the swirling tides of European society blowing toward the cataclysm of World War I, though, the generation that followed Mahler didn’t have the luxury of remaining half planted in the past, no matter how much they wanted to.

In a 1967 magazine article, Leonard Bernstein famously wrote that Gustav Mahler symbolically straddled the year 1900 with one foot planted in the traditions of 19th century Romanticism and the other in the unknown world of the 20th century. With the swirling tides of European society blowing toward the cataclysm of World War I, though, the generation that followed Mahler didn’t have the luxury of remaining half planted in the past, no matter how much they wanted to.

That generation was led by the so-called Second Viennese School, whose most famous proponents were Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, and Anton Webern. Schoenberg, the eldest of the three by a decade, would gain a reputation as the destroyer of tonal music, yet he thought of himself as squarely planted in the tradition of Austro-German music that had produced Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms. After all, when in 1897 he wrote his first string quartet, Brahms had been dead for only a few months.

He was particularly fond of Brahms, in fact, whose economical developmental techniques particularly appealed to him. A 1930 radio lecture he gave in Berlin formed the basis of a long essay proclaiming Brahms a true progressive of 19th-century music. That was in marked contrast to the then-standard perception that Brahms was the conservative, academic balance to Wagner’s progressive ideas in music and drama. (That didn’t stop a young Schoenberg from going through his own Wagnerian phase first.)

Whether Schoenberg’s development of atonal and 12-tone techniques, in the end, is considered a liberating or destructive force on Western music, partisans of both sides must acknowledge Schoenberg’s motivation: to be true to his artistic predecessors.

At the same time, he keenly felt a responsibility to advance his art and take it into uncharted territory. He was willing, too, to accept the misunderstanding (or just the lack of it) such a path would undoubtedly bring him. As he wrote in a letter in 1947, “I am quite conscious of the fact that a full understanding of my works can not be expected before some decades.... I know this, I have renounced an early success, and I know that — success or not — it is my historic duty to write what my destiny orders me to write.”

“Schoenberg and his school are romantics; and their 12-tone syntax, however intriguing one may find it intellectually, is the purest Romantic chromaticism.”

— VIRGIL THOMPSON

That inherent conflict ran through Schoenberg’s private, professional, and artistic lives. As an avant-garde composer of music most listeners found either incomprehensible or just plain ugly, his early career years were predictably lean.He taught where he could, and he leaned on the support of mentors like Mahler, who on occasion lent him rent money. Even when he gained some fame (and financial success), he continued to balance teaching and creating for the rest of his life.Schoenberg’s mental rigor was countered by physical frailty, particularly asthma. Ill effects from cold, wet winters forced him to leave teaching posts inBerlin, Boston, and New York. He landed at last in Los Angeles in 1934 and stayed there until his death.

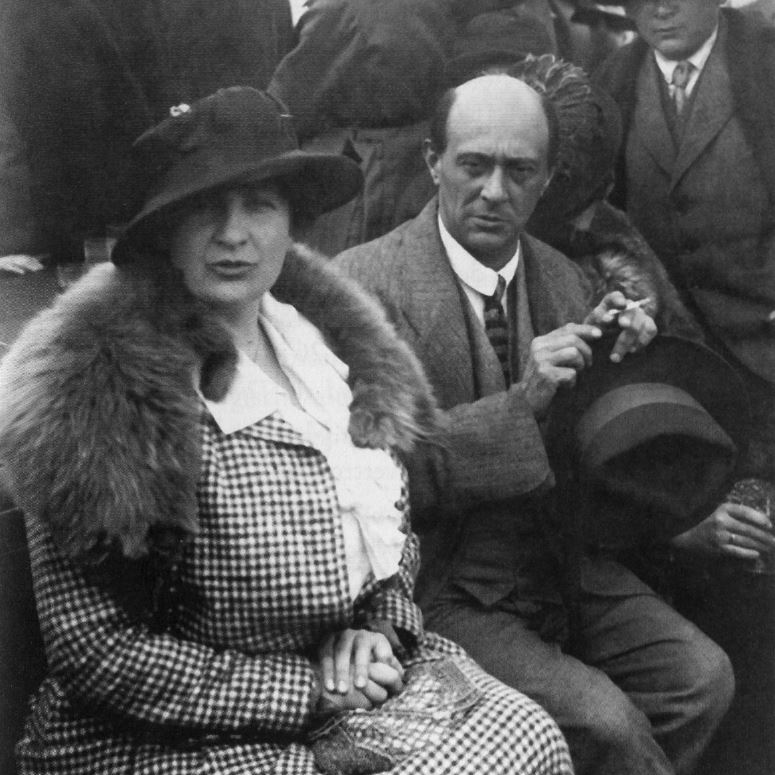

Strik's "Transfigured Night," inspired by both Dehmel's poem and Schoenberg's music.

Schoenberg arrived at the turning point of atonality because he felt the expressive possibilities of tonal music had been exhausted and that a new language was the only viable path forward. He knew that path well from his own early works. He was just 25 when he wrote his first major composition, a groundbreaking piece based on a Richard Dehmel poem. The appeal was clear: The poem’s drama is entirely psychological — a perfect vehicle for purely musical expression.

Dehmel’s theme, of transformation and the reconciliation of seemingly contradictory elements, resonated in the young composer. In a later letter to the poet, he wrote,

“Your poems ... were what first made me try to find a new tone in the lyrical mood. Or rather, I found it even without looking, simply by reflecting in music what your poems stirred up in me.”

Schoenberg’s version of “Verklärte Nacht” (Transfigured Night), then, is not song setting, but a tone poem that portrays the emotional journey of the poem. It’s done through a very traditional ABACA form, where the A sections invoke the couple walking, B the woman’s confession, and C the man’s reply. The A material is developed in response to the context of the B and C material.

“Verklärte Nacht” is Schoenberg’s reconciliation of the seeming contradictions of Brahms and Wagner. The music clearly propels the drama, but it does so through Brahmsian thematic development — and, to express the intense emotions of the characters, harmonic language stretched nearly to the breaking point. It would be just a few years before the composer decided that nearly to the breaking point was not enough.

The piece was written for string sextet, making it the first tone poem in chamber music. Schoenberg in 1917 wrote a version for string orchestra. He revised it again in 1943; that version is heard tonight.

Two people walk through a bare, cold grove;

The moon races along with them, they look into it.

The moon races over tall oaks,

No cloud obscures the light from the sky,

Into which the black points of the boughs reach.

A woman’s voice speaks:

I’m carrying a child, and not yours,

I walk in sin beside you.

I have committed a great offense against myself.

I no longer believed I could be happy

And yet I had a strong yearning

For something to fill my life, for the joys of Motherhood

And for duty; so I committed an effrontery,

So, shuddering, I allowed my sex

To be embraced by a strange man,

And, on top of that, I blessed myself for it.

Now life has taken its revenge:

Now I have met you, oh, you.

She walks with a clumsy gait,

She looks up; the moon is racing along.

Her dark gaze is drowned in light.

A man’s voice speaks:

May the child you conceived

Be no burden to your soul;

Just see how brightly the universe is gleaming!

There’s a glow around everything;

You are floating with me on a cold ocean,

But a special warmth flickers

From you into me, from me into you.

It will transfigure the strange man’s child.

You will bear the child for me, as if it were mine;

You have brought the glow into me,

You have made me like a child myself.

He grasps her around her ample hips.

Their breath kisses in the breeze.

Two people walk through the lofty, bright night.

— translation by Stanley Appelbaum

About ‘Psycho’

➤ Released: 1960.

➤ Stars: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles.

➤ Awards: Nominated for four Oscars, including best director and best actress.

➤ Trivia: The blood in the shower scene was Bosco chocolate syrup.

Bernard Herrmann was born (as Max Herman) on June 29, 1911, in New York City. He died in Los Angeles on Dec. 24, 1975

By the time Bernard Herrmann began his five-film collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock, he already was a major force in American music as both cunductor and composer. He had decided young — at age 13 — to concentrate on music and had studied at New York University and Juilliard when, at 20, he formed his own orchestra. As chief conductor of the CBS Symphony, he became known for introducing listeners to an impressive array of new and little known music.

By the time Bernard Herrmann began his five-film collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock, he already was a major force in American music as both cunductor and composer. He had decided young — at age 13 — to concentrate on music and had studied at New York University and Juilliard when, at 20, he formed his own orchestra. As chief conductor of the CBS Symphony, he became known for introducing listeners to an impressive array of new and little known music.

Along the way, he continued to compose, both for the concert hall and films. His 1941 score to The Devil and Daniel Webster earned him an Academy Award for best music — the only Oscar he would collect. His score to Citizen Kane, one of several colaborations with Orson Welles, earned him another nomination.

Psycho, from 1960, came in the middle of Herrmann’s work with Hitchcock. The landmark score uses only strings to create its claustrophobic mood — including the shrieking violins for the shower scene. Hitchcock hadn’t wanted the scene scored, but Herrmann wrote it anyway. When the director saw the scene with the now iconic music, he immediately changed his mind and ordered it kept.

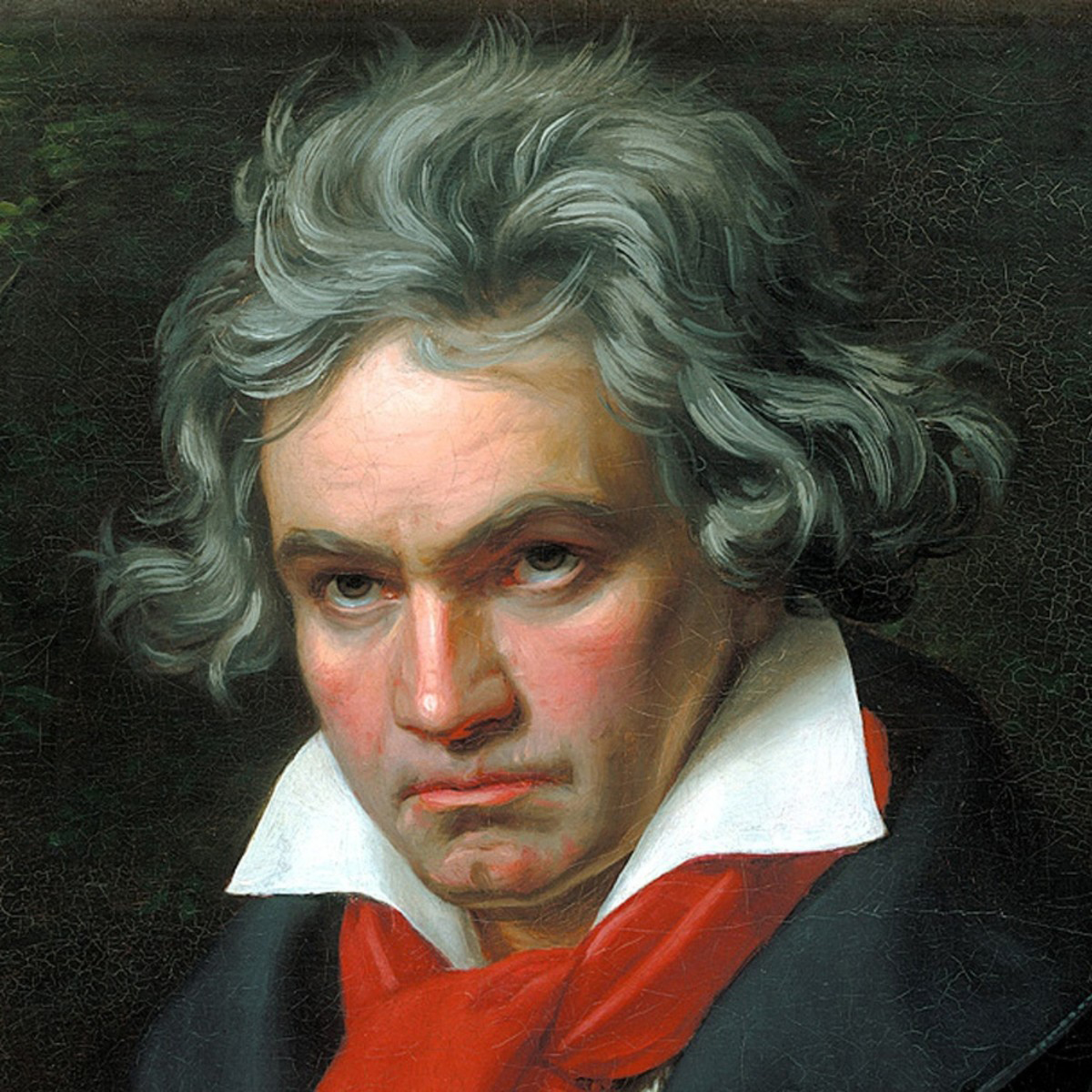

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in December, 1770, in Bonn, Germany. (He was baptised Dec. 17.) He died in Vienna on March 26, 1827.

It’s fairly reasonable that, in the program notes of symphony orchestras, one would read mostly of Beethoven as a writer of symphonies or concertos. In his last years, though, Beethoven turned inward and to more intimate forms for expression, particularly the string quartet.

It’s fairly reasonable that, in the program notes of symphony orchestras, one would read mostly of Beethoven as a writer of symphonies or concertos. In his last years, though, Beethoven turned inward and to more intimate forms for expression, particularly the string quartet.

Beethoven received an offer for a commission of three string quartets in 1822 from Prince Nokolai Galitzine, an amateur cellist whom Beethoven knew from the Russian aristocrat’s time in Vienna. Beethoven in fact wrote five quartets in the set, Nos. 12–16, now known simply as the late quartets. Like so many masterpieces through the annals of music, they were beyond the understanding of contemporary audiences and performers but are now considered among the greatest achievements of Western music.

As he had done in his symphonies, Beethoven in the late quartets creates unique and highly personal solutions to the usual compositional challenges of form, balance, and expression. The quartet No. 13 (the 14th written, but published out of order), for example, is in six movements; the usual middle movements are doubled so that there are two based on dances forms alternating with two slow movements. The reason for that extra weight became clear with the finale, a massive fugue that is an emotional wringer of its own. Beethoven understood the scope of what he had written in naming the movement Große Fuge (Great Fugue).

Completed in March 1826, the quartet was a mixed success at its premiere, with two of the middle movements encored — but not the fugue.

Beethoven’s response to the audience’s taste: “Cattle! Asses!”

Despite the composer’s confidence in his creation, the “Grosse Fuge” (the English spelling of the German name) remained a problem child. At nearly 15 minutes, it’s very long and very difficult to grasp. It’s also technically very demanding of players. Beethoven’s publisher decided to cajole him into spinning off the fugue as a standalone piece and replacing it with a new finale. Amazingly, Beethoven relented. The new finale, completed late in 1826, turned out to be the last major piece Beethoven completed before his death.

Freed from the context of its quartet, the “Grosse Fuge” has alternately enthralled and vexed listeners, composers, musicologists, and performers ever since. While the progression of the large outline of its form are easy to follow, the details of the textures and the juxtaposition of the sections have yielded analysis as polarized as declaring it Beethoven’s Art of Fugue (after the unfinished Bach masterpiece) to declaring it a mocking satire of a great fugue; from a statement of the triumph of the human spirit to a devastating acceptance of death.

If this great fugue is opaque to listeners even today, imagine the effect it had at its premiere, with its jagged main subject and complex interplay with its dissonant countersubject. The chaos the movement seems to create was even seen as a harbinger of the 20th century. Stravinsky said the “Grosse Fugue” would be eternally contemporary. The Austrian expressionist painter Oscar Kokoschka told Arnold Schoenberg, “Your cradle was Beethoven’s ‘Grosse Fuge’.”

Maybe no better testament exists on the movement’s inaccessibility to early listeners than that, in the quarter century after Beethoven’s death — when his life and music were raised to almost religious veneration — there were no public performances of the “Grosse Fuge.”

To some, the fugue seems too symphonic for a string quartet to do it justice. Starting about 1880, performances by full string orchestras began, a practice that continues today (and to tonight’s performance).

Beethoven marked that the piece was “tantôt libre, tantôt recherchée” (somewhat free, somewhat scholarly). It’s a reference to the work’s blend of fugal tradition and Romantic development; but it’s an acknowledgement that, in part, this giant undertaking was an experiment. Perhaps the mystery of the meaning of the “Grosse Fuge” is more obvious: Beethoven had been completely deaf for more than a decade when he undertook composition of the late quartets. His affliction had cost him most social interaction (and, of course, his performing career). Commission or no, his music was written to satisfy his inner muse, and the ability of others to understand it is secondary.

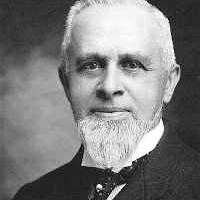

Whether he was being quite honest remains a mystery, but music publisher Mathias Artaria in 1826 told his most famous client, Ludwig van Beethoven, that people wanted a four-hand piano arrangement of his Great Fugue. The question of honesty is that the fugue was regarded as a perplexing miscue in its original role as the finale of the string quartet, Op. 130, and Artaria was trying to convince Beethoven to write a new finale.

Beethoven wouldn’t take the bait, though, until Artaria hired someone else to do the arrangement. At that point Beethoven leapt into action to create an arrangement he deemed acceptable. The result — especially in how it differs from the quartet version — is a fascinating insight into Beethoven’s vision of the “Grosse Fuge”. Sadly the manuscript had disappeared more than a century ago.

Fast forward to 2005, and a librarian at the Palmer Theological Seminary near Philadelphia, while going through the archives, found something odd. There it lay in her hands: Beethoven’s “lost” manuscript, found. As it turns out, its path to the seminary library ran through the Queen City.

William Howard Doane (1832–1915) was one of many 19th-century Cincinnatians to make a fortune in industry, in his case primarily through a woodworking machinery company. More than 70 patents are credited to him, and his mansion in Mount Auburn still stands. Doane’s real passions, though, lay in his Baptist faith and in music. He was a prolific composer, including hundreds of hymns and hymn settings among more than 2,300 works that included songs, ballads, and cantatas. (Among his best known hymns are “Safe in the arms of Jesus”, “The Old, Old Story”, “Pass Me Not”, and “Draw Me Nearer”.) He also edited more than 40 hymn collections, starting in 1861.

William Howard Doane (1832–1915) was one of many 19th-century Cincinnatians to make a fortune in industry, in his case primarily through a woodworking machinery company. More than 70 patents are credited to him, and his mansion in Mount Auburn still stands. Doane’s real passions, though, lay in his Baptist faith and in music. He was a prolific composer, including hundreds of hymns and hymn settings among more than 2,300 works that included songs, ballads, and cantatas. (Among his best known hymns are “Safe in the arms of Jesus”, “The Old, Old Story”, “Pass Me Not”, and “Draw Me Nearer”.) He also edited more than 40 hymn collections, starting in 1861.

In 1890, Doane was in Berlin. While there, he apparently won the Beethoven manuscript at auction. After his death, his family continued his religious philanthropy. Eventually — a half century after Doane acquired it — the Grosse Fuge piano manuscript was donated to the Palmer Seminary, where it lay for more than 50 more years.

Its rediscovery left the classical world agog. Palmer Theological Seminary promptly auctioned off the manuscript, fetching $1.95 million to boost its endowment. The buyer, a hedge fund manager and billionaire, in 2006 donated the manuscript to the Juilliard School.

Producers

ArtsWave

Charles H. Dater Foundation

Paula Steiner Charitable Fund

Directors

R.C. Durr Foundation

Kentucky Arts Council

Greater Cincinnati Foundation

Louise Dieterle Nippert Musical Arts Fund of the Greenacres Foundation

Louise Taft Semple Foundation

Founders

James R. & Angela Cassidy

Duke Energy Foundation

Macy’s Foundation

The Milburn Family Foundation

The William O. Purdy, Jr. Foundation Fund of the Greater Cincinnati Foundation

RPI Data Graphics Solutions*

St. Elizabeth Healthcare

Elsa H. Sule Foundation

Maxwell C. Weaver Foundation

The Wohlgemuth Herschede Foundation

Sponsors

Central Bank

Jim Fausz*

Fischer Homes

John B. Goering

Mr. & Mrs. Paul E. Houston

Kathleen Martin & Dr. Joseph Martin

Party Source

Schneller & Knochelmann Plumbing, Heating and Air

Charles & Ruth Seligman Family Foundation

Patrons

Mr. & Mrs. William Butler

Robert & Sarah Connatser

Sue & Don Corken, Jr.

Daniel & Bradie Courtade

Radisson Hotel Cincinnati Riverfront*

Schultz Marketing Communications, Inc.

Scripps Howard Foundation

Harry & Carol Sparks and Macy’s Foundation

Mary Vande Steeg Wagner

Katie & Steve Wolnitzek

Wilbert L. and Ellen Hackman Ziegler

Benefactors

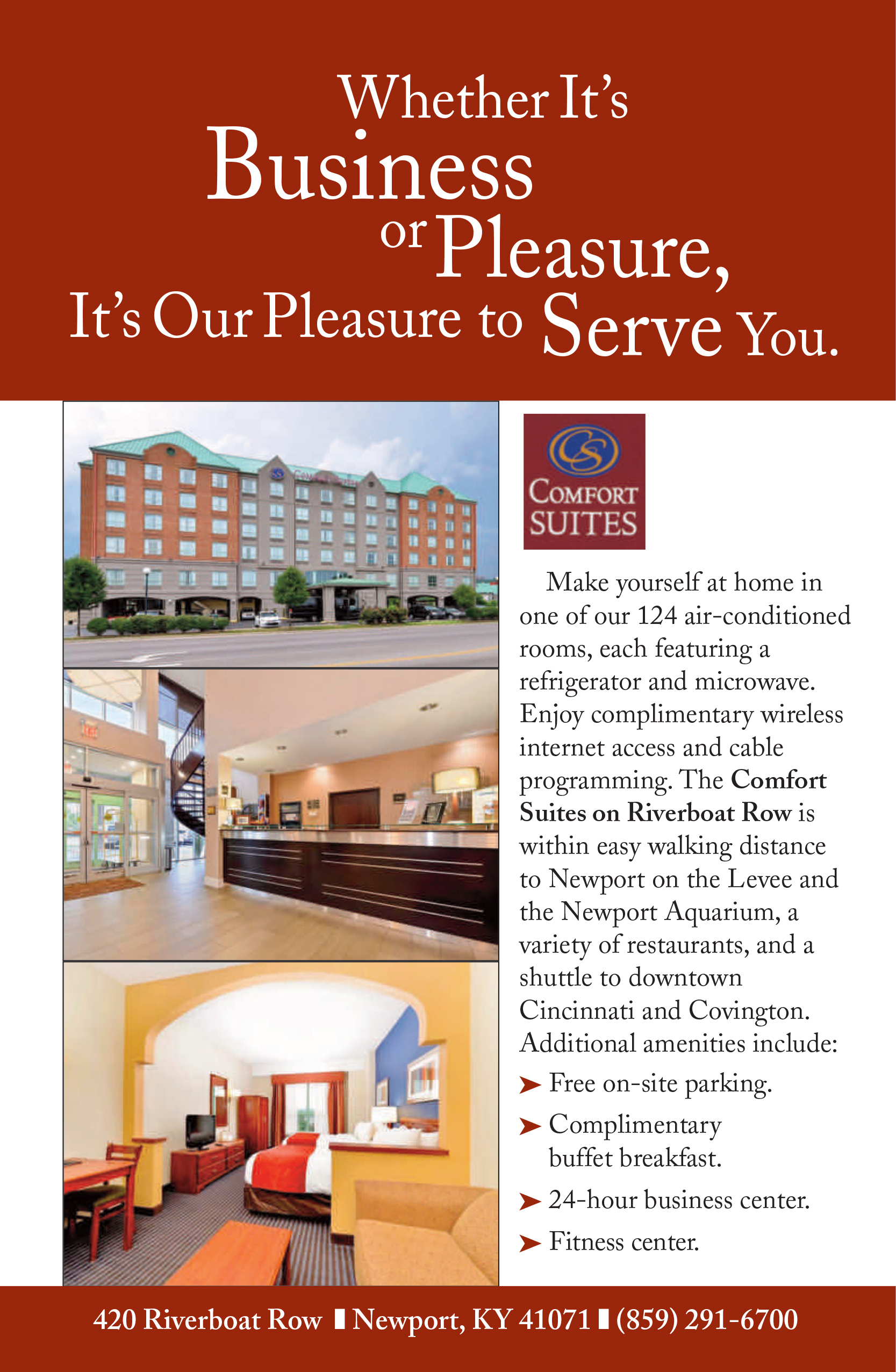

Carol & George Beddie Comfort Suites*

Associates

Mr. Doug & Dr. Lavonne Adams Marja Wade Barrett

Ben and Sharon Kuo

Chad Martin

Chuck & Julie Geisen Scheper Jim & Erika Smith

Carol Swarts

Mary Vande Steeg Wagner Mr. & Mrs. Robert Wylly

Family

Anonymous

David & Jan Arno

Ron Carmack

Michael & Cindy Cason State Farm Agencies Fund Jim & Judy Jenkins Sheriff Chuck & Ruth Korzenborn Mrs. Betty M Pogue

Mary Ann Robinson Kathryn & Vishnoo Shahani Ann Silvers

Cathy L. Stickels

Joe & Lise Tewes

Gerry & Tony Zembrodt

Friends

Anonymous

Matt Ackermann

Perriann Allen & John Norwine Glenna Angel in honor of Lesley Cissell

Tara & Mark Bailey

Carol Bethel

Charles & Joan Cerino Edmund Choi

Lyn & Drew Collins

Rob & Trudy Craig

Terrie Cunningham

Joseph & Christina Finke

Janice & Marshall Hacker

Troy Hitch

Lenore Horner

Janet & Dennis Jasper

Mr. & Mrs. Dale Johnson

Lynn Klahm

Edward & Rita Larkin

Mary & Keith Ledford

Mr. & Mrs. Michael Maier

Sue Marshall

John & Janet Middleton

Joan & James Noll

Paul Picton

Gary & Janet Sogar

Jon Stiles

Liz Sypolt in memory of Edwin Sypolt

Marty and Donald Unger

Mr. & Mrs. Herb Wedig

Gail Weibel

Leisa Williamson

Dave & Sarah Wilson

Laurence J. Wulker, CFP

John & Ellen Zembrodt

Neighbors

Two anonymous friends of the KSO

Ginny T. Bolte

Mark & Jeanne Bowman

Larry & Janis Broering

Lisa Bryson

Sonny & Joyce Burnette

Debbie Campbell in honor of Paula Steiner

Lesley Cissell

Michael & Melanie Crail

Jeff & Monica Egger

Mr & Mrs. Clifford E. Fullman

Linda & Hartmut Geisselbrecht

Dennis & Lorna Harrell

Sis & Warren Heist

Bev Holiday

Jeff & Vicki Jehn

Paul & Liz Listerman

Mark & Mary Ann Michael

Virginia Neff

Jim & Pat (deceased) Niehaus

Mark & Audrey Petrakis

Blair and Jane Pohlman

Edward Polaski and Cheryl Fast

Cynthia A. Priem and Nancy Johnston

Ruth Ryan

Nancy Rzonca

Deacon Bill Theis

Jerri Roberts & Jim Thomas

Ruth Ann Voet

George & Nancy Whitton

Tamra M. Womble

Rick and Maureen Zalla

Gifts received between Oct. 1, 2019, and Oct. 23, 2020.

* – Denotes in-kind donations.

Join the family

For Community Circle information, write to P.O. Box 72810, Newport, Ky., 41072; call (859) 431-6216; or email angela@kyso.org.

Producer: ............................... $25,000+

Director: ......................$12,000–24,999

Founder: ...................... $5,000–11,999

Sponsor: ......................... $2,500–4,999

Patron: .............................$1,000–2,499

Benefactor: ........................... $750–999

Associate: ............................. $500–749

Family: ................................. $250–499

Friends: ................................ $100–249

Neighbors: ................................$50–99