40th ANNUAL

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL

Saturday, September 18 :: 5 & 8 PM

BRENTANO QUARTET

PRELUDE IN F MINOR FROM THE

WELL-TEMPERED CLAVIER), BOOK TWO,

BWV 881 (c1740)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), arr. Mark Steinberg

STRING QUARTET IN F MINOR, OP. 20 NO.5 (HOB.III:35) (1772)

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Allegro moderato

Menuetto

Adagio

Finale: Fuga a due soggetti

MOLTO ADAGIO (LYRIC FOR STRINGS), FROM STRING QUARTET NO. 1 (1946)

George Walker (1922-2018)

STRING QUARTET IN F MAJOR, OP. 135 (1826)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Allegretto

Vivace

Lento assai, cantanto e tranquillo

Grave, ma non troppo tratto – Allegro

The 8 PM performance is made possible by contributing sponsor the JMR Barker Family Foundation.

Thank you to our Corporate Sponsor

PRELUDE IN F MINOR FROM THE WELL-TEMPERED CLAVIER), BOOK TWO, BWV 881

Johann Sebastian Bach (b. Eisenach, Germany, March 21, 1685; d. Leipzig, July 28, 1750)

Composed c1740; 5 minutes

.jpg) Bach compiled the collection of Preludes and Fugues found in Book Two of The Well-Tempered Clavier over a period of 20 years after completing Book One. Often simply referred to as the '48', the importance of the collection is reflected in the fact that they are among the very few works by Bach to have been played continuously by musicians from the time of their composition to the present day. While such monumental works as the B minor Mass, the St Matthew Passionand the Brandenburg Concertos were forgotten after Bach's death, copies of these Preludes and Fugues circulated widely among his large family, his friends, his many students and their descendants for well over a century. Haydn, for example, was able to make a study of their mastery of the free-form Prelude and the contrapuntal Fugue by turning to hand-copied manuscripts, venerating the skill Bach displays in all 96 pieces: the 48 Preludes and 48 Fugues.

Bach compiled the collection of Preludes and Fugues found in Book Two of The Well-Tempered Clavier over a period of 20 years after completing Book One. Often simply referred to as the '48', the importance of the collection is reflected in the fact that they are among the very few works by Bach to have been played continuously by musicians from the time of their composition to the present day. While such monumental works as the B minor Mass, the St Matthew Passionand the Brandenburg Concertos were forgotten after Bach's death, copies of these Preludes and Fugues circulated widely among his large family, his friends, his many students and their descendants for well over a century. Haydn, for example, was able to make a study of their mastery of the free-form Prelude and the contrapuntal Fugue by turning to hand-copied manuscripts, venerating the skill Bach displays in all 96 pieces: the 48 Preludes and 48 Fugues.

For many of us, the calm pathos of the F minor Prelude by Bach will be complemented by the sophisticated homage to Bach found in the spirited closing fugue of the Haydn string quartet which follows.

Joseph Haydn (b. Rohrau, Lower Austria, March 31, 1732; d. Vienna, May 31, 1809)

Composed 1772; 24 minutes

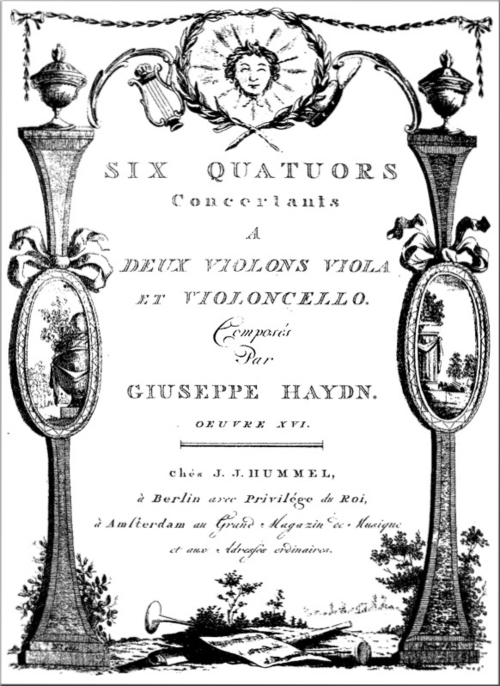

When Haydn’s Op. 20 quartet collection was issued in an unsanctioned printing in Amsterdam and Berlin in 1779, its publisher (Hummel) put an emblem of a full sun or sun god atop two neo-classical pillars on the front cover – and this is why the six quartets are still occasionally called the Sunquartets. Thanks to wide distribution through both official and unofficial channels, the collection did much to popularize the medium of the string quartet during Haydn’s lifetime. Mozart admired the collection. Beethoven copied them out to better understand their craft. And, at the end of the 19th century, Brahms owned the original autograph manuscripts, which he donated to the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, where they remain to this day.

When Haydn’s Op. 20 quartet collection was issued in an unsanctioned printing in Amsterdam and Berlin in 1779, its publisher (Hummel) put an emblem of a full sun or sun god atop two neo-classical pillars on the front cover – and this is why the six quartets are still occasionally called the Sunquartets. Thanks to wide distribution through both official and unofficial channels, the collection did much to popularize the medium of the string quartet during Haydn’s lifetime. Mozart admired the collection. Beethoven copied them out to better understand their craft. And, at the end of the 19th century, Brahms owned the original autograph manuscripts, which he donated to the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, where they remain to this day.

Each of the Op. 20 quartets has a distinctive character. Each instrument speaks with an independent voice as an equal contributor to a seamless four-part texture. One of two quartets in the minor key, the F minor quartet opens with a sustained, emotionally intense theme over a pulsing accompaniment. The mood is serious and purposeful; the tension is only slightly eased with the second theme. The Menuetto, too, is unusually severe, allowing just a glimpse of a folkdance in its central trio section. The slow third movement, now in a brighter major key yet still maintaining a feeling of poignancy, takes its underlying rhythmic pulse from the siciliano dance. Over it, the first violin weaves improvisation-like passages of great beauty.

Then there’s a surprise. The F minor is one of three Op. 20 quartets to have a fugal finale. While drawing inspiration from a form associated with the past (Bach was in mid-career when Haydn was born), Haydn’s F minor fugue is sprightly and forward-looking in spirit. It is based on two short, independent subjects (due soggetti), the first of which presents a melodic pattern familiar to the Baroque. Melodically, it bears a close resemblance to a choral fugue in Handel’s Messiah (‘And with His stripes’) and to the A minor Fugue in the Second Book of Bach’s 48. The double fugue proceeds in a hushed manner, marked sotto voce. Its tension and contrapuntal complexity increase steadily throughout the movement, as Haydn works his way through many contrapuntal techniques, until the music bursts out in a fortissimo canon in the crowning moment of an exceptional quartet.

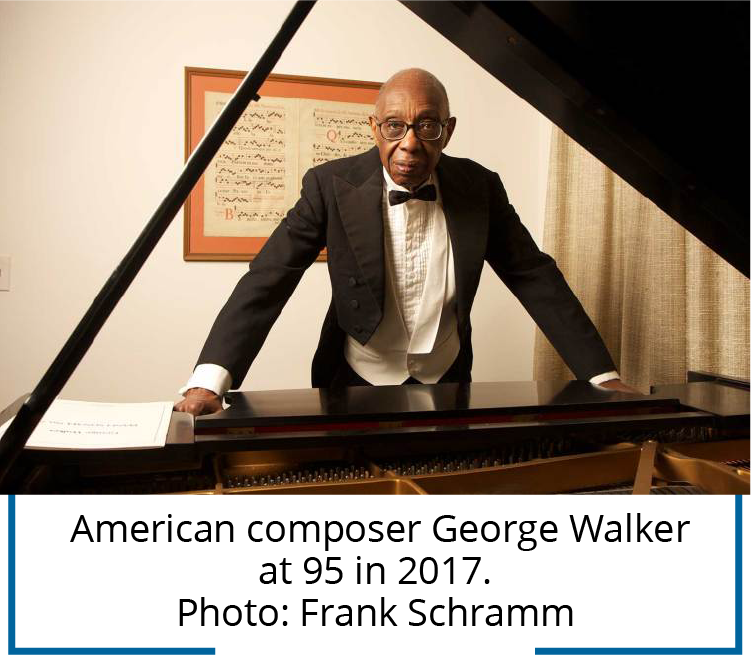

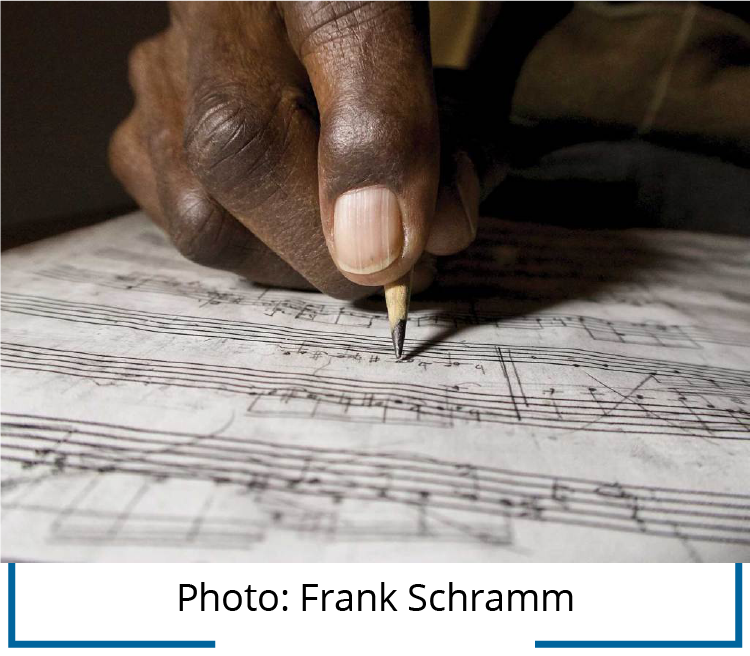

George Walker (b. Washington, DC, June 27, 1922; d. Montclair, NJ, August 23, 2018)

Composed 1946; 6 minutes

Composer, pianist and educator George Walker earned a string of ‘firsts’ during a long life. They were capped, perhaps, by becoming the first black composer to win the Pulitzer Prize, when he was 74, for his Lilacs, for voice and orchestra. Recognition for his achievement, however, did not reach far. “I got probably more publicity nationwide than perhaps any other Pulitzer Prize-winner,” Walker told The Washington Post almost 20 years later. “But not a single orchestra approached me about doing the piece or any piece. My publisher didn’t have sense enough to push. It materialized in nothing.” That same year, 2015, The Guardian’s international edition ran a story headed “George Walker: the great American composer you've never heard of.”

Composer, pianist and educator George Walker earned a string of ‘firsts’ during a long life. They were capped, perhaps, by becoming the first black composer to win the Pulitzer Prize, when he was 74, for his Lilacs, for voice and orchestra. Recognition for his achievement, however, did not reach far. “I got probably more publicity nationwide than perhaps any other Pulitzer Prize-winner,” Walker told The Washington Post almost 20 years later. “But not a single orchestra approached me about doing the piece or any piece. My publisher didn’t have sense enough to push. It materialized in nothing.” That same year, 2015, The Guardian’s international edition ran a story headed “George Walker: the great American composer you've never heard of.”

With Clifford Curzon and Rudolf Serkin among his piano teachers, the newly graduated Walker built a reputation as a pianist, touring internationally for a few years. At Curtis, his composition teachers included Rosario Scalero, teacher of Samuel Barber, and, in Paris, Nadia Boulanger, teacher of pretty well every American composer of a certain generation. While teaching paid the bills – he was a professor and chaired the music department at Rutgers University 1969-92 – Walker remained productive as a composer. His catalogue includes over 90 works and he continued composing until his later years. Within five or six years of his death at the age of 96, he had premières of a fifth Sinfonia, a work for cello and orchestra and Bleu, for violin unaccompanied. “Why keep working?” Walker was asked at the time. “I want more people to hear my work,” he replied. “I want people to get acquainted with my music.”

Walker wrote his String Quartet No. 1 shortly after graduating from Curtis, in 1946. Its slow movement, Molto Adagio, quickly gained traction as an independent piece. That year, it was broadcast by the Curtis student string orchestra as Lament, dedicated to the composer’s recently deceased grandmother. A professional première took place in Washington the following year. Retitled Lyric for Strings, at the request of Walker’s publisher, it soon became one of the most frequently performed orchestral works by an American composer. Like Samuel Barber’s Adagio for strings (1936), which is also the slow movement of a string quartet, Walker’s Molto Adagio can generate a profound feeling of loss, hope and comfort in an audience. A calm, spacious atmosphere is established as the strings interweave a sombre falling phrase, broken by reflective chordal cadences. At the midpoint, the music builds to an intense climax as the chords turn jagged and bring a short-lived lyrical melody. But the prevailing mood remains sombre to the concluding chords.

Ludwig van Beethoven (b. Bonn, Germany, December 15 or 16, 1770; d. Vienna, Austria, March 26, 1827)

Composed 1826; 25 minutes

Op. 135 is Beethoven's final string quartet and his last word in a medium he had chosen to explore life's journey. Written in poor health, after a traumatic period in his life resulting in an uneasy reconciliation with his nephew Karl, its music was nevertheless quickly composed. Its directness and clarity of language appears to be far removed from the crescendo of complexity and soul-searching of the other late quartets. But beneath the surface there is a subtlety and richness to the music, together with an intricacy of emotional worlds. Take the opening movement, for example. A calm, meditative exterior presents a smooth facade. But underneath, all is complexity and a wealth of invention, wit and terseness of expression. Then there's the Scherzo. It is uncomplicated enough in its structure. But the music works itself up into a frenzy as the first violin plays a wild dance over a furious phrase in the lower strings. The phrase is repeated nearly 50 times! Then, the slow movement brings a complete contrast. Half as long as Beethoven's previous slow movement, it is profound in its timeless gravity, as the music adds layers of emotion, one on top of another. Without doubt, this is among the most moving of all Beethoven's slow movements. It's as though all his troubles and emotional conflict during the summer of 1826 find brief expression in the gentle, occasionally painful solemnity of the music.

Op. 135 is Beethoven's final string quartet and his last word in a medium he had chosen to explore life's journey. Written in poor health, after a traumatic period in his life resulting in an uneasy reconciliation with his nephew Karl, its music was nevertheless quickly composed. Its directness and clarity of language appears to be far removed from the crescendo of complexity and soul-searching of the other late quartets. But beneath the surface there is a subtlety and richness to the music, together with an intricacy of emotional worlds. Take the opening movement, for example. A calm, meditative exterior presents a smooth facade. But underneath, all is complexity and a wealth of invention, wit and terseness of expression. Then there's the Scherzo. It is uncomplicated enough in its structure. But the music works itself up into a frenzy as the first violin plays a wild dance over a furious phrase in the lower strings. The phrase is repeated nearly 50 times! Then, the slow movement brings a complete contrast. Half as long as Beethoven's previous slow movement, it is profound in its timeless gravity, as the music adds layers of emotion, one on top of another. Without doubt, this is among the most moving of all Beethoven's slow movements. It's as though all his troubles and emotional conflict during the summer of 1826 find brief expression in the gentle, occasionally painful solemnity of the music.

The main characteristics of the two middle movements resurface with the interplay of rhythmic assertiveness and lyrical affirmation in the finale. Beethoven writes ‘Muss es sein?’ (‘Must it be?’) over the former, with a rising, questioning sort of musical figure. Over the latter, with its assertive, answering figure, he writes ‘Es muss sein!’ (‘It must be!’). Over the whole he writes ‘The Resolution reached with difficulty.’ It is as though Beethoven is pushing the language of music towards the rhetoric of speech – much as he did with the cello and double bass recitative leading to the Ode to Joy in the Ninth Symphony. He then proceeds to attempt a resolution of the argument posed in the introduction to the finale, eventually finding resolution in a mood of positive, even joyous reconciliation, tinged with questioning. Just as comic moments can illuminate the darkest sides of a Shakespearean tragedy, so Beethoven’s final string quartet ends with a touch of good humor and wit.

— Program notes © 2021 Keith Horner.

Comments welcomed: khnotes@sympatico.ca