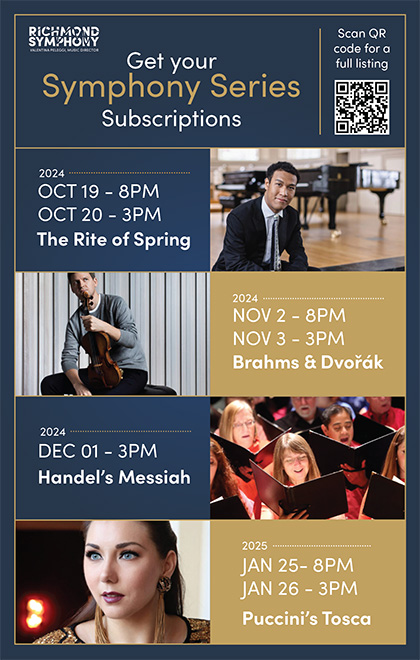

THE RITE OF SPRING

Valentina Peleggi | Conductor

Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918) | La Mer | |

Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937) | Piano Concerto in G Major for Piano | |

INTERMISSION | ||

Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971) | Le Sacre du Printemps | |

When Music Director Valentina Peleggi designs a concert program, she makes it a priority to juxtapose different ways of composing, different ways of translating perceptions into sound. It’s all the more intriguing when the composers she has lined up are all operating within the same milieu — as, in this case, Paris in the early 20th century. “It’s so striking to me that different languages that express a similar reality can coexist at the same time, even in the same place on Earth,” she says about this program of Debussy, Ravel, and Stravinsky — all of whom knew each other.

Claude Debussy: La Mer

Like painters, many composers have responded to the challenge of attempting to render impressions of the sea using the tools of their art. As Peleggi points out, Debussy in fact “treats the orchestra like paint, with splashes of colors — all within an incredibly sophisticated mathematical structure” in La Mer, composed between 1903 and 1905. But his original impetus was not so much a particular sea setting so much as memories awakened by thoughts of the sea. He grew impatient with those who insisted on a literal approach to this score.

Debussy decorated the walls of his studio with Japanese prints, including Katsushika Hokusai’s 19th-century woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa — already a visual icon by that time. He even chose a section from this image to illustrate the first edition of La Mer. Hokusai’s stylized depiction of the sea’s immensity, along with his animated use of detail, finds its counterpart in Debussy’s intricately nuanced method of painting with a large orchestra.

La Mer holds a unique position in Debussy’s oeuvre. As the early biographer Louis Laloy observed, this music conveys “an impressionism of the emotions, translated into harmonies unique to the world.” Debussy’s “three symphonic sketches,” as La Mer is subtitled, do not conform to any conventional symphonic design. Nor can they be explained away as mere “programmatic” depictions of seascapes. They exist in a mysterious zone between musical abstraction and illustration. La Mer’s score exerts much of its effect through the power of suggestion.

The first part or “sketch,” titled “From Dawn to Noon on the Sea,” offers a marvelous example of how Debussy exploits register, timbre, and gradations in volume to evoke the primordial spectacle of the day coming into being across the vastness of the sea. This majestic music abounds with kaleidoscopic sonorities to convey a sense of awe-inspiring, untiring flux. The movement culminates inevitably in the climactic arrival of high noon.

The middle sketch, “Play of the Waves,” uses a flickering waltz-like meter and delicate orchestral arabesques to lighten the mood; much of this music hints at a dreamscape. In the final sketch, “Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea,” the sea’s elemental power again comes to the fore. Debussy creates textures that surge and swell with almost violent ferocity. Floating in and out of focus is a siren-like melody — a kind of musical hallucination — while the full orchestra unleashes its power with a reprise of the majestic climactic passage from the first sketch returns and a final exhilarating rush.

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto in G

Following the death of Debussy in 1918 and the sea change caused by the destruction of the First World War, Ravel gained the status of France’s preeminent composer during the 1920s. It was in this decade that he took up the challenge of writing a concerto for his own instrument, the piano. In fact, Ravel produced two of them, side by side. The Piano Concerto in G, which draws on efforts going back to 1914, ranks among the French composer’s finest masterpieces.

Inspired by his experiences touring the United States in 1928, he started writing this work the following year to showcase his skills as a pianist. However, another commission in 1929 temporarily interrupted work on the Concerto in G. This was the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, Ravel’s only other work in the genre. Once the latter was completed in 1930, Ravel returned to the Concerto in G. But as a result of his deteriorating health, he decided against playing the solo part at the premiere in Paris in 1932. That honor fell to his friend Marguerite Long, while Ravel conducted. The Concerto in G was also included on the program of the very last public performance that Ravel conducted (in November 1933).

Ravel’s deep admiration for Mozart is especially evident in the Concerto in G. So is his newfound enchantment with music he had discovered during his four-month tour of North America in 1928 — including that of George Gershwin, whose Concerto in F from 1925 especially impressed Ravel.

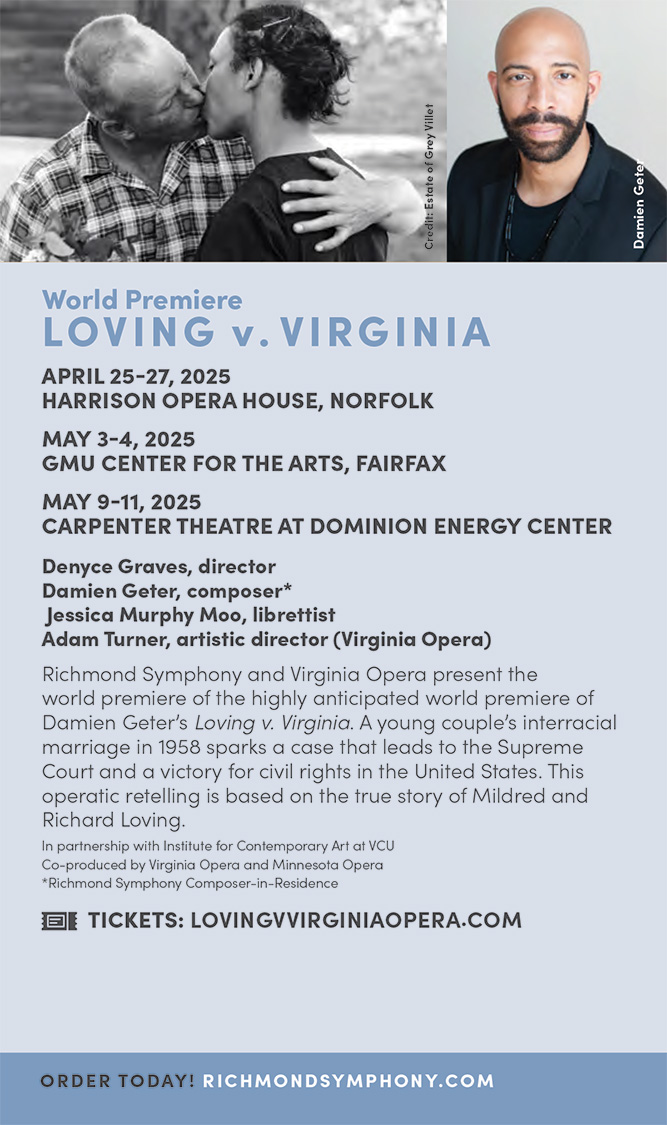

As the more “classical” of his two concertos, the Concerto in G blends the melodic poignancy of Mozart, the elegance of French music, and folklike simplicity, spicing it all with a hint of jazz — always in Ravelian proportions. Our soloist is Clayton Stephenson, whom Valentina Peleggi determined to bring to Richmond to collaborate with the symphony as soon as she heard his performance as a finalist in the 2022 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition.

Another influence on this music is the innocent wonder of childhood, whose recollection signaled another kind of paradise for Ravel: the first sound we hear is the circus-like cracking of a whip. Calling us to attention, Ravel gives the first theme, as a delightful surprise, to the piccolo, enhancing the atmosphere of childlike fantasy. Although Ravel limits himself to a chamber orchestra, he uses its colors to paint a wondrous, kaleidoscopic range of sonorities: a theme park of delectable textures and detours.

The spirit of Mozart comes to the fore most clearly in the Adagio assai. Although Ravel never actually quotes his predecessor, the deceptive simplicity of the piano’s long opening soliloquy, along with the graceful pacing of the woodwinds’ entrances, strikes a hauntingly “Mozartean” note.

The circus whip comes back in the brief final movement, where Ravel resumes the funhouse attitude of the first movement — but takes it up several notches with jazzy giggles from the E-flat clarinet, trombone slides, trumpet fanfares, and nimble percussive colors. The soloist is all the while put to work producing dizzying, acrobatic patterns. With mischievous abruptness, Ravel repeats the four chords that set the movement spinning, using the bang of a bass drum to draw the curtain.

Igor Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring

The Russian Igor Stravinsky became involved in the feverishly creative milieu of pre-World War One Paris. He had been a young discovery of the enormously influential showman (and fellow Russian émigré) Sergei Diaghilev. The Ballets Russes company, which Diaghilev established to cater to Parisians’ passion for “exotic” themes appropriated from Eastern cultures, staged important productions of music by Debussy and Ravel. It also became an important platform for the late-20-something Stravinsky.

Diaghilev commissioned Stravinsky’s first full-length original ballet to a scenario based on a familiar Russian fairy-tale. This resulted in The Firebird and made the Russian composer an international celebrity overnight in 1910. Stravinsky was still busy with its composition when he began working on The Rite of Spring (published under its French title as Le Sacre du printemps).

Collaborating with the mystically inclined archeologist and painter Nikolai Roerich, Stravinsky worked up his own scenario for this new ballet, hoping to evoke the spirit of archaic Russia. He later recalled that he had had a dream involving “a pagan ritual in which a chosen sacrificial virgin danced herself to death.”

The “scenes of pagan Russia” contained in The Rite of Spring were unveiled in the late spring of 1913 at the recently completed art nouveau Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The riot-inducing first performance has become the stuff of legend. It’s important to note that the audience’s violent reaction was directed not at the music but at the radically new, weirdly gestural choreography devised by Ballets Russes star Vaslav Nijinksy. Instead of conventionally graceful balletic gestures, Nijinsky had his dancers contort in violent, earthbound patterns. The battling factions in the audience became so noisy that they eventually drowned out the music.

Bad publicity is better than no publicity, of course: outrage gave way to fascination as the run continued. Stravinsky’s music almost immediately established itself as arguably the most influential work of 20th-century musical innovation. From its original conception, Rite combined music with visceral images of the elementary bond between human bodies and the earth. Inherent in the score, therefore, is a fascinating tension between the primal and the ultra-modern.

“This music is the opposite of Debussy’s lines and effects,” Peleggi notes. “Stravinsky takes a totally different approach and calls for a completely different way of playing, with percussion and brass that is brighter and more piercing, like a laser.” Unlike the warmth and “round, golden, dark, European sound” of La Mer, Stravinsky’s ballet is “closer to an American sound.”

The Rite of Spring is divided into two parts, each prefaced by hypnotically evocative introductions. Part One (“The Adoration of the Earth”) centers on ancient Slavic rituals, which proceed from playful to fiercely combative. “All this,” Stravinsky says, “is interrupted by the procession of The Old Wise Man, who kisses the earth,” after which “the first part ends in a frenzied dance of the people drunk with spring.”

In contrast to the daytime setting of the first part, Part Two (“The Sacrifice”) takes place at night. It culminates in the “Chosen One” from among the young women being glorified, surrounded by a circle of Old Wise Men, and dancing herself to death in a sacrificial dance. At the end, the elders rush forward to prevent her lifeless body from touching the earth, raising her up to the sky.

Rite’s propulsive, jagged, lurching rhythms are probably its best-known feature. Stravinsky’s rhythmic innovations liberated meter and rhythm from the predictable, symmetrical patterns that had dominated Western classical music since the Baroque.

The composer’s innovative use of the orchestra is another gripping feature of this music from the very opening, when the bassoon plays at the high end of its register to suggest the rawness of untrained village singers. Stravinsky often highlights orchestral sections (especially percussion) previously relegated to a background role, at the same time de-centering the traditional “backbone” role played by the strings.

While Rite builds several times to a kind of brutalizing frenzy before its final meltdown, the music also explodes in moments of overwhelming exuberance, such as the anarchic joie de vivre of spring awakening heard in the opening scene. This is perhaps the greatest paradox of this seminal score: Stravinsky’s ability to evoke a joyful, affirmative sense of the life force that underlies even the most violent extremes of the music.

(c)2024 Thomas May