“When it comes to a masterpiece like the Beethoven Violin Concerto,” says Music Director Valentina Peleggi, “I always check: when was the last time the orchestra performed it, and how many times?” To her surprise, she discovered that Beethoven’s iconic concerto hadn’t been programmed by the Richmond Symphony in over two decades.

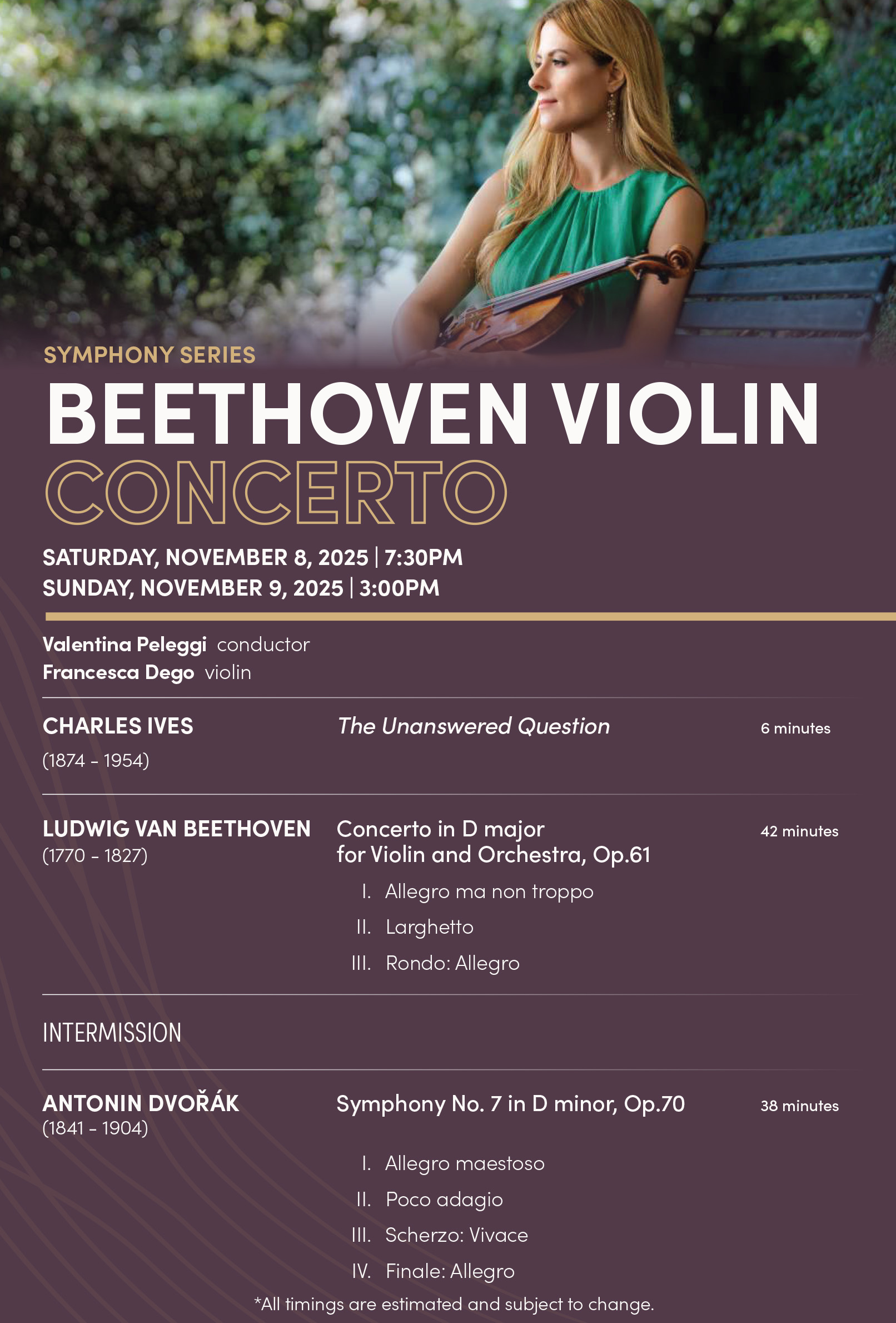

“You cannot hide in the Beethoven Violin Concerto,” she adds. “It’s so clean and virtuosic – but not romantically virtuosic. It’s pristine. It’s about intonation, about articulation” – just the thing for violinist and author Francesca Dego, who left a deep impression with her Richmond Symphony debut in the Busoni Violin Concerto in 2024.

Peleggi singles out the unusual way Beethoven opens his concerto with four timpani strokes, barely audible – a moment full of mystery. “I often ask: what is that meant to convey? Is it martial? Or is it a question? When I conducted this piece in Italy with a chamber orchestra, I suddenly felt it is more about searching: not a gesture of reassurance, but a question mark.”

That image of a question mark became the key to this program’s architecture. Peleggi has decided to preface the Beethoven with The Unanswered Question by Charles Ives, moving directly from Ives’s music into the concerto, without a break – no time for applause. “There’s this big question left hanging in the air, and it transitions suddenly into Beethoven’s ambiguous opening. I’ve never done it before, but I wanted to experiment.”

Dvořák’s Seventh Symphony also addresses themes of questioning, searching, and transformation. The first movement begins in unrest and ambiguity, and the symphony as a whole traces a dramatic emotional arc as Dvořák, like Beethoven before him, fuses personal voice with public expression.

Charles Ives: The Unanswered Question

Charles Ives is often regarded as the guiding spirit of the “maverick” or experimental tradition in American music. A native New Englander, Ives took the title of this short, mysterious piece (originally from 1908 but revised later) from a line by the Transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. At one point, he planned to pair The Unanswered Question with another short work, Central Park in the Dark, as a set titled Two Contemplations.

The “contemplation” in this piece involves nothing less than a cosmic mystery. Ives imagined a scenario addressing what he called “the perennial question of existence.” The music is structured in a completely new way for its time. Instead of unfolding as a single narrative, it presents three separate “tracks” of sound layered on top of each other, each following its own path. These overlapping layers create a kind of musical collage – and make us more aware of how music behaves in space, not just in time.

Ives assigned each of the three layers a character. The first is a slow-moving background of quiet chords played by the strings. Their wide spacing and serene mood give the impression of a timeless, distant hymn. Ives compared this to “the silence of the Druids – who know, see, and hear nothing.” These soft chords continue almost imperceptibly in the background and never react to the rest of the music.

The second layer is a five-note phrase, described by Ives as “the question,” which is usually played by a solo trumpet. It’s heard seven times throughout the piece. Each time, it begins with a note that doesn’t belong to the peaceful harmonic world of the strings, making it feel out of place – unsettling, unresolved.

The third and most animated layer involves a small group of woodwinds – flutes and others – who represent “the hunt for the invisible answer.” With each repetition of the question, they respond with increasingly agitated and complex music. At first they seem to offer calm replies, but over time their answers grow frantic and sarcastic, spinning into chaos. Ives builds tension by letting the tempo accelerate and the volume rise with each round of answers. By the end, the winds seem to lose their way entirely.

On the sixth question, Ives subtly alters the trumpet’s phrase. When the seventh and final version is played, there is no response at all. Ives described this final moment by saying that the “fighting answers” realize the futility of their efforts and begin to mock the question itself. “The strife is over for the moment.” Afterward, only the distant, unaffected music of the strings remains – gently pulsing in what Ives called “undisturbed solitude.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

Ideas for the Violin Concerto appear in the same notebook Beethoven was using for the Fifth Symphony. While the latter took years to hammer into being, he produced the concerto in a matter of months in 1806. But Beethoven kept his soloist – a friend and former prodigy named Franz Joseph Clement – waiting until the very last minute. He completed the score barely in time for the premiere, just two days before Christmas.

Beethoven had written his piano concertos up to that point for himself as soloist, but here he tailored the work to Clement’s musical personality. Clement was admired for the delicacy and refinement of his playing – qualities Beethoven highlights throughout the piece. He introduced the concerto on 23 December 1806 at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien, where he served as concertmaster – a bit more than a year after Napoleon’s forces had first taken the city.

For all the celebrity of the soloist, the work didn’t catch on immediately. While not as outwardly radical as the Eroica, the Violin Concerto was path-breaking in its own way, and may have disappointed audiences expecting a showpiece. There are few documented performances over the next three decades, and the concerto had to wait for champions such as Joseph Joachim.

“The profound influence of French ‘revolutionary’ music on Beethoven’s style is reflected principally in his cultivation of motivic relationships, his handling of instrumental structures, and in the inspiration he derived from its general character and sonorities,” writes Robin Stowell in a monograph on the work. He details how Beethoven drew on the exponents of the French violin school, especially Giovanni Battista Viotti, transforming their idiomatic gestures from mere bravura into embellishments of profound musical ideas.

The opening movement is vast – nearly as long as an entire Classical symphony. Yet instead of epic struggle, it conveys a sense of leisurely exploration. Beethoven emphasizes this by delaying the soloist’s entrance – the violin’s teasing phrases hold back the songful first theme even longer. At the same time, elements familiar from his more overtly “heroic” works are embedded in the musical fabric. The mysterious repeated beats from the opening timpani, for example, recur obsessively. When the violins take them up for the first time – as a D-sharp – they momentarily cloud the serene mood with harmonic ambiguity.

Beethoven shows a preoccupation with the violin’s upper register, used to rapturous effect in the Larghetto. This meditative music revolves around a gentle G major theme that does not develop but returns, reframed in varied instrumental settings, while the soloist weaves ecstatic decorations around it. A brief cadenza leads directly into the finale: a rustic Rondo that blends echoes of the hunt (with rousingly scored horns) with a dance theme whose infectious energy brings the concerto down from the heavens to earth.

Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70, B. 141

Antonín Dvořák began to gain an international reputation with the publication of his first set of Slavonic Dances in 1878 – a boost for Czech pride, with the novelty of their “Czechness” enhancing their appeal abroad. But Dvořák was determined not to be pigeonholed as a composer of picturesque local color. He wanted to claim a place in the mainstream symphonic tradition – and he had no better ally than Johannes Brahms.

The premiere of Brahms’s Third Symphony in 1883 particularly impressed Dvořák. He responded to it as a personal challenge to deepen and intensify his own symphonic voice. A timely opportunity arrived when the Royal Philharmonic Society in London, which had recently named him an honorary member, commissioned a new symphony. Dvořák composed the Seventh in just a few months and conducted the premiere in April 1885.

Dvořák chose D minor – the same key Beethoven used for his Ninth Symphony, which was dedicated to the Royal Philharmonic Society. The result is a tightly structured, emotionally intense work, darker in mood than his later and more famous New World Symphony. It also marked a turning point in his career: with this symphony, Dvořák made a powerful case that he deserved a place in the mainstream tradition of Europe’s leading composers – at a time when many in the German-speaking musical establishment still regarded Slavic composers as outsiders. Critics in Vienna and Berlin often dismissed Czech and other non-German artists as mere “folk colorists,” not serious symphonists. With the Seventh Symphony, Dvořák answered that prejudice head-on, writing a work as structurally rigorous and emotionally profound as anything by Brahms or Beethoven.

The somber character of this music is especially apparent in the first and fourth movements. Emerging from the depths of the orchestra, the first theme seems to rise from an abyss. The music gathers energy as the trumpets blaze and the orchestra surges, giving way to a second theme from the flutes and clarinets with a touch of pastoral calm. A tragic climax comes in the recapitulation – only to dissipate on an unsettling final chord.

Alongside these public statements, the Seventh also carries a note of private grief: Dvořák was still mourning the death of his mother, who had passed away in late 1882. Some have likened the slow movement to a Requiem. This music shows Dvořák’s gift for subtle, evocative orchestral color.

Even within such a weighty framework, the composer makes space for the Czech-inspired rhythmic fire that made his Slavonic Dances famous. The Scherzo brims with dancing energy, while the central Trio unfolds like a lyrical promise of renewal.

But the finale brings us back to the tragic world. A restless, brooding theme dominates, though flashes of sunlight break through. The final climax arrives with violent force. Even a shift to D major in the closing bars cannot quite dispel the storm clouds that have gathered by the work’s end. The impact is lasting and grave – an ending that, perhaps, also implies a question mark.

(c)2025 Thomas May