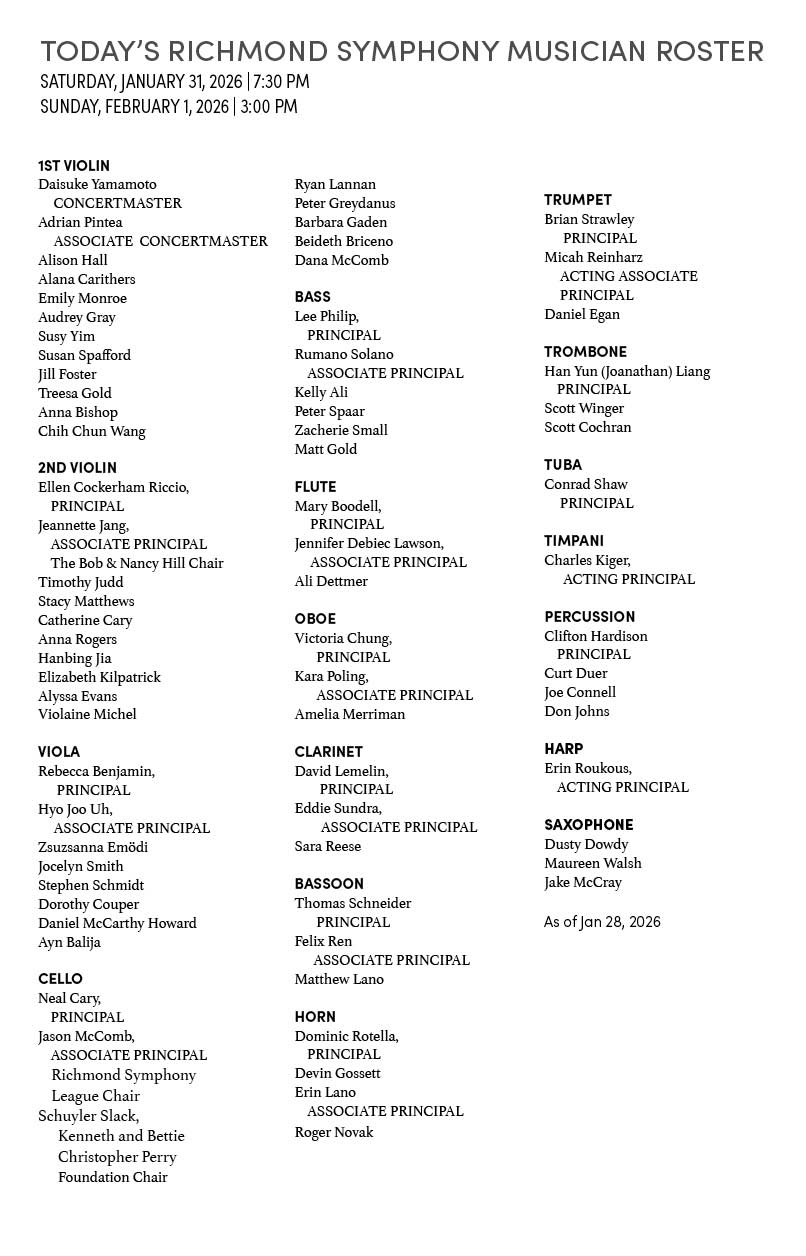

SATURDAY, JANUARY 31, 2026 | 7:30PM

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2026 | 3:00PM

CONRAD TAO PLAYS GERSHWIN

Ben Manis | conductor

Conrad Tao | piano

Conrad Tao: Flung Out

Gershwin: Concerto in F

Mozart: Symphony No. 41 “Jupiter”

One of the pleasures of this program is watching artists inhabit multiple worlds at once. Guest conductor Benjamin Manis – equally at home in the opera pit and the symphonic hall – leads a concert that invites a similar fluidity from its soloist. Conrad Tao appears in a dual capacity: first offering his own work as a composer, Flung Out, and then taking the keyboard for Gershwin’s Concerto in F.

Music Director Valentina Peleggi chose this pairing to let different generations of American innovation speak to each other – Gershwin’s jazz-inflected exuberance set alongside Tao’s contemporary, exploratory voice. As she puts it, “Conrad Tao is a young American, and Gershwin is one of the most famous American composers – so the program is anchored in an American theme as we approach the country’s 250th anniversary this year.”

To balance these modern currents, the second half of the program turns to Mozart’s final symphony, written in 1788, just a few years before his early death. As Peleggi notes, the “crystal clarity of Mozart’s Classical style” serves as a counterweight – a reminder of the European tradition that American composers have long engaged with, sometimes embracing it, sometimes pushing against it.

Conrad Tao: Flung Out

At 31, Conrad Tao has already carved out a singular place in American music – a pianist-composer whose boundary-defying imagination has made him one of the most compelling voices of his generation. Celebrated as both a brilliant interpreter of the classical repertoire and an adventurous creator of new work, Tao became a natural choice in 2024 when orchestras around the country marked the centenary of Rhapsody in Blue. Like Gershwin – who was only 25 when he shook up the musical world with that iconic score – Tao moves fluently among idioms and cultural lineages, composing and performing with the same restless creative curiosity.

From the outset, Tao resisted the idea of crafting a straightforward homage – “I didn’t want to write a ‘companion piece,’ I wanted to do it my way,” he recalls – yet with distance he realized that the piece had nonetheless absorbed something of Rhapsody in Blue’s basic dramatic arc.

As Gershwin did, Tao makes his home in New York, and he thought deeply about what the “music of city life” means now. For him, the urban soundscape carries its own “whiz, crash, bang”: he remarks that he has been inspired by car horns since childhood – everyday noise serves as raw material. The opening of Flung Out captures that frenetic energy – “like pinballs flying around,” as he puts it – noisy, joyful, and a little manic.

Much as Rhapsody in Blue eventually opens into a lush, sentimental melody, Flung Out moves from that boisterous opening into a more overtly melodic space, giving way to a long-lined, expressive episode that offers warmth and breadth after the whirlwind. Later, in the final section, Tao “digs into the piano in a more soulful way,” drawing inspiration from the improvisational, searching quality of Keith Jarrett’s playing.

Another thread woven through the piece comes from a different facet of New York life: the nightclub. The title Flung Out grew from Tao’s reflections on dance floors as “spaces of communal movement and connection,” but also places shaped by outsiders, “people who are flung out and slung out into the margins.”

He wanted the music to inhabit the sensation of being both inside and outside the rhythmic groove – belonging and not belonging at once. The rhythmic writing channels what Tao calls the “punchy show-biz energy” of Gershwin while filtering it through his own love of dance music and the surprising harmonic colors of contemporary club culture.

Flung Out shares with Rhapsody both a stylistic flexibility and a theatricality. “I was influenced by Gershwin’s ability to combine multiple musical languages and his distinctive rhythmic energy – and also by the underlying dramaturgy,” Tao says. “I wanted to evoke the feeling and the form of Rhapsody in Blue without explicitly quoting it.” His inclusion of improvised moments in the solo part extends that lineage – a performer-composer shaping the work from the inside.

Gershwin: Concerto in F

George Gershwin’s rise from a crowded tenement on New York’s Lower East Side to the concert stages of America is one of the great musical stories of the 20th century. The son of Ukrainian- and Lithuanian-Jewish immigrants who fled growing persecution in the Russian Empire, he grew up surrounded by the restless energy of a city shaped by new arrivals and new sounds. That early mix of cultures would later feed his own instinct to blur musical boundaries.

As a teenager, Gershwin entered the world of commercial music head-on. He worked as a song plugger in the bustle of Tin Pan Alley, absorbing every style that passed through the publishers’ doors. By the early 1920s, he was already known for his unforgettable melodies and rhythmic snap — but the success of Rhapsody in Blue suddenly revealed another dimension: Gershwin had ideas too large to fit inside the popular song.

The morning after the Rhapsody premiere, the conductor Walter Damrosch asked him to write a full piano concerto. Gershwin accepted, though it meant leaping into a musical arena dominated by the European classical tradition. The concerto became his way of engaging with the European Classical lineage that American composers have long alternated between embracing and reshaping.

For Rhapsody in Blue, Gershwin prepared a score for two pianos and handed it to Ferde Grofé – the gifted arranger for Paul Whiteman, the bandleader who had commissioned the piece – to orchestrate. But when he took up his Concerto, Gershwin was determined to stand entirely on his own feet. He orchestrated every measure himself, embracing the challenge with astonishing confidence.

Conrad Tao, who speaks of the Concerto in F with real affection, refers to the result as “a very beautiful orchestration – not without its problems - but deeply satisfying.” He is especially fascinated by the work’s dual identity: Gershwin striving to prove his legitimacy in the classical concerto tradition while still drawing on his theater savvy. “Because it’s Gershwin, I can’t help but think of it as theater music,” Tao says. “In the piano’s very first entrance, I can literally feel the lighting change.”

The Concerto in F opens in a spirit of pure New York: bright, bustling, and touched with Broadway swagger. Gershwin even threads the rhythm of the Charleston into the orchestral fabric, which he described as capturing “the young enthusiastic spirit of American life.” When the piano finally enters, the mood softens into a lyricism that hints at the blues-infused poetry to come. These two ideas — the dance pulse and the long, dreamy melodic line – keep circling each other, changing costumes, swapping roles, and creating a first movement that feels by turns urban, elegant, and full of possibility.

The slow movement brings a different kind of nighttime. A solo trumpet opens with what Gershwin called a “nocturnal tone,” and the piano responds in a hushed, almost conversational way. Blues harmonies drift through the texture, not as spectacle but as atmosphere — the sound of a city catching its breath.

The finale shakes off the stillness with a burst of speed. Gershwin builds the movement as a kind of musical chase, bringing back ideas from the first two movements, now transformed by quicksilver rhythms and a propulsive rondo theme. He once described the ending as “an orgy of rhythm,” and even in the concert hall it arrives with the high-voltage excitement of a Broadway curtain-raiser.

The Concerto in F was Gershwin’s first large-scale concert work built completely on his own terms — his orchestration, his language, his cross-pollinated musical worldview. It stands as the moment he proved he could take the tools of classical form and make them sound unmistakably, exuberantly American.

Mozart: Symphony in C major, K. 551 (“Jupiter”)

The final symphony that Mozart completed—later nicknamed the “Jupiter”—grew out of an extraordinary burst of creativity in the summer of 1788. Mozart wrote his last three symphonies in roughly six weeks, a pace that would be impressive under any circumstances. That he achieved this during a period marked by financial strain, the death of an infant daughter, and worries over his wife Constanze’s health only deepens the sense of wonder. Yet from that difficult stretch emerged a trilogy of works, each a masterpiece with its own character and scope.

The last of these, the Symphony in C major, K. 551, eventually took on the “Jupiter” nickname—a posthumous addition but one that fits. The music carries a commanding, larger-than-life energy that suggests the immortal Olympian ruler evoked by the name.

Exactly why Mozart wrote these symphonies remains a mystery. No surviving commission explains their origin, and earlier generations imagined him composing them simply for his own artistic satisfaction. Modern scholars are more cautious: Mozart typically wrote with specific performances in mind, even if the paperwork has vanished. Whatever the circumstances, the “Jupiter” is the work of a composer fully in command, thinking on a large scale and writing with supreme confidence.

For all its status as a pinnacle of Classical style, the “Jupiter” reaches backward and forward at once. Mozart draws on the lively, interwoven style of the Baroque while also pointing toward the muscular musical language Beethoven would make his own.

The “Jupiter” announces its expansive character right away: punctuated by drums and trumpets, the opening measures establish a bold attitude of C major that gives the music an immediate sense of purpose. Soon after, Mozart lightens the mood with a more agile idea whose playful trills add a touch of theatrical wit, sharpening the contrast between the movement’s ceremonial and conversational sides.

In the Andante, muted strings create a soft halo around the woodwinds, giving the music its distinctive sense of suspended calm. Small shifts in harmony briefly darken the atmosphere before the texture opens again into more lyrical territory, a gentle ebb and flow shaped with a singer’s sense of breath.

The Minuet begins with a slithery descending line that lends an unexpected hint of tension to its otherwise stately profile. The sound thins and softens in the middle section, which is characterized by a more relaxed, pastoral warmth.

Then comes the finale, the part of the symphony that has earned the most admiration over the years. Mozart starts with an unassuming four-note motive in a simple pattern that listeners of the time would have instantly recognized from church “Amen” cadences. As the movement gathers force, Mozart draws on techniques he admired from the Baroque—especially the art of weaving independent musical lines together—while keeping everything grounded in the clarity of Classical style.

In the final minutes, Mozart stacks and interlocks his various musical strands so naturally as to they suggest a sudden, exhilarating revelation. This brilliant concluding section goes beyond a display of craftsmanship to revel in the high spirits of creativity itself, a reminder of this composer’s ability to make complexity sound natural and joyful.

(c)2026 Thomas May