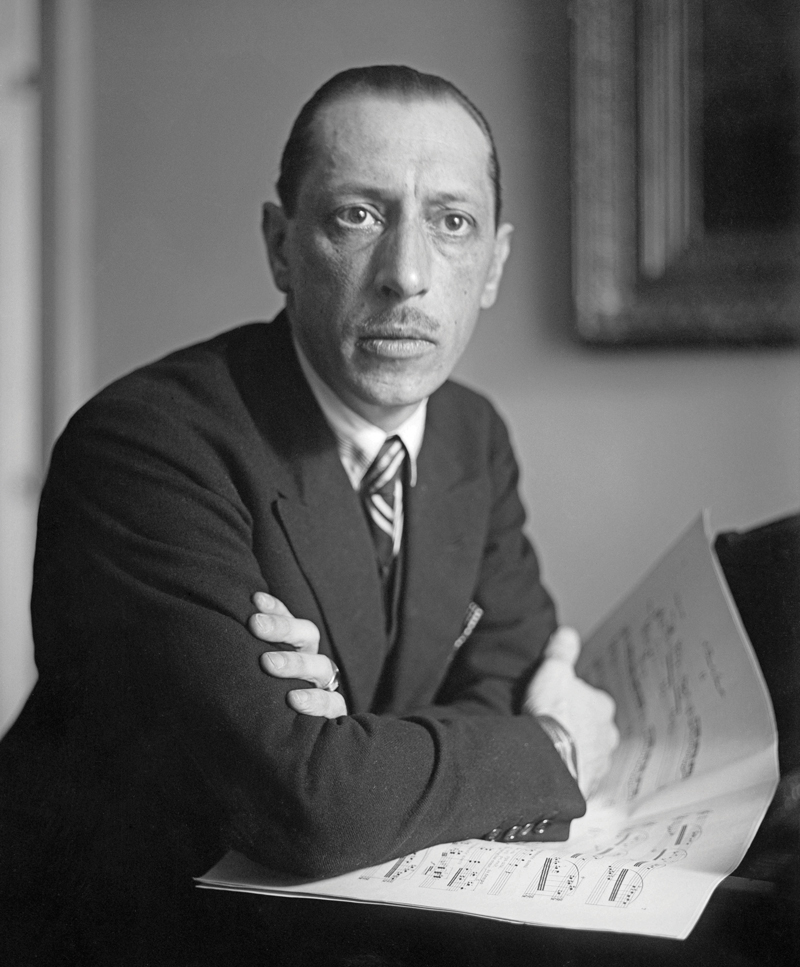

Igor Stravinsky

Born: June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia

Died: April 6, 1971, New York City

Symphony of Psalms

- Work Composed: 1930

- Premiere: December 13, 1930 in Brussels by the Société Philharmonique de Bruxelles, Ernest Ansermet conducting

- Instrumentation: SATB chorus, 5 flutes (incl. piccolo), 4 oboes, English horn, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 5 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, harp, 2 pianos, strings

- Duration: approx. 21 minutes

Igor Stravinsky was surrounded by music as a child. His father was a famous opera singer and his mother loved to play the piano. Important composers of the day, such as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Modest Mussorgsky, were frequent guests in the family’s Saint Petersburg apartment, and Igor and his three brothers regularly attended the opera and ballet at the nearby Mariinsky Theatre. Stravinsky began college as a law student but spent much of his time studying music theory, piano and composition. He eventually became a student of Rimsky-Korsakov’s and devoted himself entirely to music. In his late 20s, Stravinsky found immediate fame when Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, chose him to write music for the company’s new production, The Firebird. The ballet was an overnight hit, and the fruitful partnership led Stravinsky to compose two more of his most famous works, Petrushka and Rite of Spring.

After World War I, he moved with his wife and children to France to be closer to the musical happenings in Europe. Stravinsky had been raised in the Russian Orthodox Church but became disillusioned as a young man. In France, he reconnected with his faith, finding comfort and inspiration in the spiritual texts. When his friend, the famed conductor Serge Koussevitsky, approached him with a commission for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 50th-anniversary season, Stravinsky turned to his long-held idea of setting psalms. He believed these poems “had been written for singing” and welcomed the chance to create a large-scale work devoted to these texts.

Koussevitsky’s request had no stipulations on form or style and Stravinsky took this to heart, with an unusual approach to instrumentation and the notion of what constitutes a symphony. He omitted the smooth sonorities of violins, violas and clarinets from the orchestra and added two pianos and extra flutes, giving the texture a strikingly austere and bright quality. The chorus is treated not as a separate entity but as an integral part of the ensemble. As Stravinsky explained, the voices and instruments “are on equal footing, neither outweighing the other.”

The work, in three movements played without pause, begins with a pronounced E minor chord. Stravinsky manipulates this common chord of E, G and B notes by emphasizing the middle G note and spacing it within very high and low registers, leaving a wide gap in the midrange. According to musicologist Michael Steinberg, the surprising effect of this chord’s spacing makes it sound “as though it were the first triad in the history of the world.” Rushing oboes and bassoons follow this chord with an anxious melody before the ensemble settles into an ostinato groove and the chorus enters with the ritualistic tone of a Gregorian chant on the words “Hear my prayer, O Lord.”

The opening chord repeats, punctuating the texture between statements, and the music gathers strength at the words “Be not silent.” The movement reflects the meandering solitude of the text and builds continuously, both through dynamics and lengthening phrases, to a resounding climax. The final G major chord stands in powerful contrast to the first E minor chord, with the full force of the brass commanding attention.

Stravinsky called the second movement “an upside-down pyramid of fugues,” in that it begins small, with one oboe, and gradually expands to the full force of the ensemble. The solo oboe is soon joined by the flutes, further depicting the tip of the pyramid with their high registers. The second fugue is given to voices alone, which build onto the structure with the addition of the low bass notes. The final section combines the two fugues, weaving them into a dense fabric of sound. A stunning setting of the text occurs when the orchestra drops out and the voices sing alone, “He set my feet upon a rock.” The lack of foundation from the orchestra instills the words with a delicate vulnerability. It is then all the more powerful when voices and instruments join forces at the words “He put a new song in my mouth.”

The prayer for a new song is answered with the “Alleluia” that opens the final movement. The reserved but joyful music resembles the deep tolling of church bells. After a moment of murky ambiguity, a quick rhythmic pattern is introduced, beginning a dance-like section full of exultations. Stravinsky later wrote that this section was inspired by “a vision of Elijah’s chariot climbing the heavens.” The conclusion sees the return of the slower music that opened the movement, with steady intonations of C minor. Stravinsky described the section, saying, “this final hymn of praise must be thought of as issuing from the skies; agitation is followed by the calm of praise.” A final “Alleluia” is uttered like a sigh before the work gently comes to an end, turning at the last moment from the minor mode into a bright C major chord.

—Catherine Case