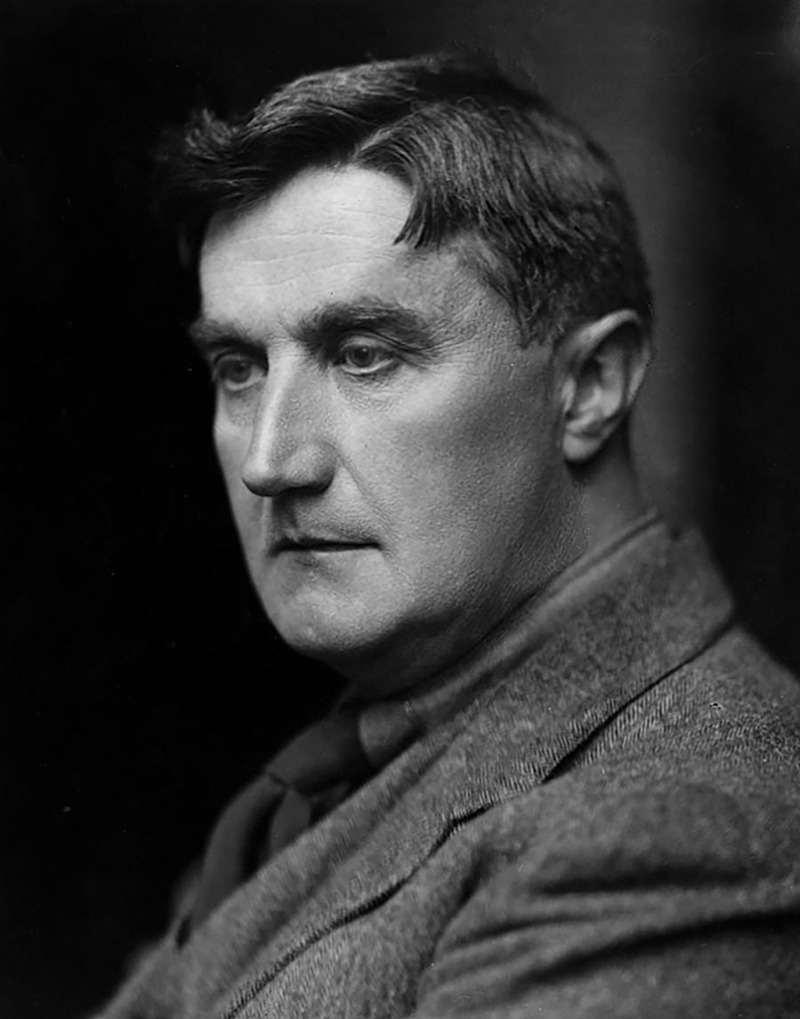

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born: October 12, 1872, Gloucestershire, England

Died: August 26, 1958, London, England

Serenade to Music

- Work Composed: 1938

- Premiere: October 5, 1938 at Royal Albert Hall, London, conducted by the composer

- Instrumentation: SATB chorus, 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), oboe, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, triangle, harp, strings

- Duration: approx. 14 minutes

Ralph Vaughan Williams came from a prominent family whose ancestors included biologist Charles Darwin and the famous potter Josiah Wedgwood. Born in 1872 in the Gloucestershire village of Down Ampney, Vaughan Williams was supported in his love for music by his family, including his aunt, who was the first to give him piano and music theory lessons. Although he always wanted to be a composer, he struggled with his technique in school. His cousin recalled overhearing classmates talk about “that foolish young man, Ralph Vaughan Williams, who would go on working at music when he was so hopelessly bad at it.”

He continued to work diligently for many years, traveling to Berlin and Paris to study with Max Bruch and Maurice Ravel, honing his craft and searching for his voice. Upon returning home, Vaughan Williams took an intense interest in the musical traditions of his own country. During the early 19th century, England’s musical landscape was dominated by German composers such as Wagner and Brahms, who were revered for their works’ complexity and dense orchestral writing. Vaughan Williams sought to counterbalance these influences by exploring the rich traditions of Elizabethan-era church music and the folk songs of rural England. This research guided his own development as a composer and contributed to his creation of a distinct national style that infused contemporary classical music with elements of England’s musical past.

In 1935, the 63-year-old Vaughan Williams completed his Fourth Symphony, a bleak and haunting work that shocked audiences with its uncharacteristic darkness. The composer was perhaps responding to his time serving in the First World War, where he transported wounded soldiers from the front lines, as well as reacting to the worsening situation in Europe. Vaughan Williams’ social activism continued throughout World War II, when his work on behalf of German refugees eventually led to his music being banned by the Nazis.

Following the Fourth Symphony, Vaughan Williams returned to his more familiar pastoral style to compose his Serenade to Music in 1938. The work was commissioned by the influential English conductor Sir Henry Wood and was premiered on October 5, 1938 at the Royal Albert Hall in London, at a concert celebrating Wood’s 50 years on the podium. Over the course of Wood’s career, he introduced British audiences to new works by composers such as Mahler, Sibelius and Bartók, and did much to promote the music of his fellow countrymen, Elgar, Britten and Vaughan Williams. His most lasting legacy remains the founding of the Promenade Concerts in 1895, now known as the BBC Proms. This summer concert series remains a vital part of London’s cultural life to this day.

The Serenade to Music is dedicated to Wood, “in grateful recognition of his services to music,” and is written for 16 solo voices and orchestra [in tonight’s performance, sections of the Chorus and Chorus soloists will sing the solo passages]. The vocal parts were composed for specific singers, each one a star in the music scene at the time and each with connections to Wood. The score includes their names in the preface and their initials are spread across the music next to each entrance. Due to the logistics of recreating the original score as intended, Vaughan Williams made alternate versions for future performances, including one for four soloists, another for full chorus and one for orchestra alone.

The text for the Serenade comes from Act Five, Scene One of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Vaughan Williams stitched together words spoken by four characters — the lovers Jessica and Lorenzo, and Portia and her maid — as they all speak of the power of music and the beauty of the night. The scene takes place in a moonlit garden while musicians play nearby.

The whole of the Serenade is a study in lush beauty and lyricism that evokes a summer evening. The tender opening sets a warm tone with harp arpeggios and a flowing solo violin melody. Murmuring woodwinds add to the texture with a second theme before the voices enter with soft chords that emerge seamlessly from the instrumental sound. The orchestra retreats as the first vocal solo climbs upward to join the lone violin for an intimate moment on the words “sweet harmony.” More solos follow, building to the first of two sweeping climaxes with all voices singing together.

A brisk fanfare changes the mood to introduce the text, “Come, ho! And wake Diana with a hymn!” This is soon followed by the second climactic moment, an outpouring of sound that perfectly depicts the words “And draw her home with music.” The brass fanfare repeats briefly before a delicate transition and the return of the solo violin melody from the opening. The work ends in quiet stillness with the violin and soprano solo again meeting in “sweet harmony.” This time, the words are echoed in serene chords sung by the chorus as the music recedes into silence.

—Catherine Case