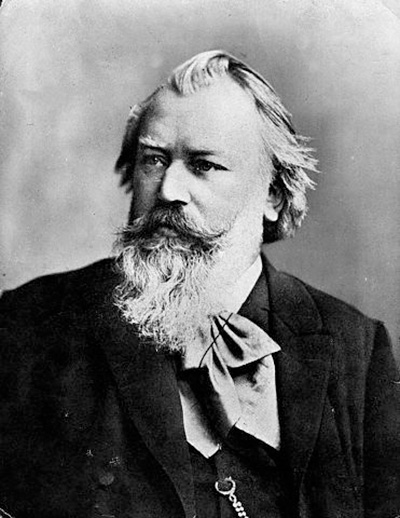

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Tragische Ouvertüre (“Tragic Overture”), Op. 81

- Composed: 1880

- Premiere: December 26, 1880, in Vienna, Hans Richter conducting the Philharmonic Orchestra

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1913, Ernst Kunwald conducting.

- Most Recent: March 2011, Louis Langrée conducting.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 13 minutes

Brahms composed his one-movement Tragic Overture, Op. 81 in 1880, around the same time he was working on his Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80, which he wrote in gratitude for an honorary doctorate from the University of Breslau. He often wrote pairs of works in which one work complemented or contrasted with the other. In this case, the Tragic Overture is somber and intense while the Academic Festival Overture is witty and jubilant. Brahms himself remarked to a friend, “One weeps while the other laughs.” Ironically, like many of his compositions from this period, the Tragic Overture was written during a summer vacation in the peaceful Austrian resort town of Bad Ischl, about 170 miles from his home in Vienna. Numerous celebrities vacationed in this town, including fellow composers such as Johann Strauss, Jr. But the serene surroundings starkly contrast with the overture’s turbulent character.

The exact significance of the title of the Tragic Overture remains uncertain. Brahms, who rarely offered insights into his compositions, told one friend he could not find a proper title for the work, and had considered alternatives such as Overture to a Tragedy and Dramatic Overture. Some have speculated that the work was conceived as a prelude to a new production of Goethe’s famous play Faust. The theory that it could have been connected to Goethe is supported by the fact that Brahms drafted its second main theme some 20 years earlier, during the late 1860s, while working on the Alto Rhapsody, a work for alto, male chorus and orchestra that sets a poem by Goethe. However, no definitive connection to Goethe or any other author or work of literature has ever been verified. Some musicologists have proposed instead that Brahms had originally intended to use the theme in the early draft in his First Symphony, which he composed between 1855 and 1876. Each — the symphony, the Alto Rhapsody and the Overture — explores a conflict between opposing forces that has often been interpreted as psychological or existential struggle. Yet each concludes differently: the symphony ends triumphantly, the Rhapsody ends peacefully and the Tragic Overture concludes with a return to the unresolved tensions of its opening.

Brahms’ contemporaries and 20th-century commentators offered a variety of interpretations of the overture’s meaning. Hermann Deiters, a music critic and friend of Brahms’, heard it as depicting “a strong hero battling with an iron and relentless fate; passing hopes of victory cannot alter an impending destiny.” Donald Frances Tovey, an English contemporary of Brahms’ known for his insightful analyses of instrumental music, proffered a similar reading, describing the overture as expressing “human defiance against a dark destiny.” Much of the work’s psychological battle is conveyed through contrasts: loud, forceful passages played by the full orchestra alternate with quieter, lyrical, almost peaceful interludes often performed by the strings and solo winds.

The brooding movement opens in an extraordinary way: two loud, defiant, full-orchestra chords immediately give way to a low, soft timpani trill. This unexpected, abrupt shift to a subdued gesture departs from the continuous melodic introductions typical of Brahms. The contrast, however, anticipates the similar juxtapositions and shifting moods that characterize the entire overture, both from phrase to phrase and across longer adjacent sections. As the trill concludes, the main theme begins with a quiet, unsettled phrase in the strings that quickly erupts into bold, agitated gestures from the entire orchestra followed by an aggressive restatement of the main theme. Although the first large section is mostly dominated by force and tension, it ends with a passage featuring a plaintive oboe solo followed by warm, almost serene trombone chords. But despite these gentler gestures, the movement’s agitation is perpetuated by the nervous syncopations in the accompanying strings.

As with the meaning, the formal structure of the overture has presented interpretive challenges. Many overtures have three sections in which the first (the exposition) presents the main melodies, the second (the development) changes them and the last (the recapitulation) restates them, though usually with a few variants. Brahms’ Tragic Overture, however, might better be understood as comprising two large sections, the second of which compresses the functions of both development and recapitulation. While Brahms used this procedure in other works, this one has a few unique characteristics. The first section introduces a wealth of short, contrasting melodic ideas, with some commentators hearing as many as 11, yet not all reappear in the second section. Another striking feature occurs when new material is introduced just after the second section’s opening restatement of the main theme. This insertion begins in a markedly slower, quieter manner and continues with quirky imitative phrases. Although gentle in character, it interrupts the restatement of the opening ideas, and in so doing contributes to the portrayal of a moody, troubled protagonist.

Brahms often previewed his new works in private gatherings of close friends. For the Tragic Overture, he created a four-hand piano version that he played with his beloved friend Clara Schumann before the public premiere. Another close friend, violinist Joseph Joachim, facilitated another trial performance, this time played by the orchestra at Joachim’s music school in Berlin. These types of read-throughs were important to Brahms because he valued his friends’ feedback and he sometimes made slight revisions, in some cases changing the balance of the orchestral instruments. The official premiere of the Tragic took place in December 1880 in Vienna, with Hans Richter, a loyal supporter and friend of Brahms’, conducting the Philharmonic Orchestra. Less than a year later, in October 1881, the work received its American premiere with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under George Henschel, another friend of Brahms’ and the orchestra’s founding conductor. American conductors quickly took up the work, with Theodore Thomas leading performances in New York the next month and then, in May 1882, in Cincinnati.

The Tragic soon secured a place among Brahms’ canonic works and continues to be performed regularly today. The composer’s handwritten manuscript is now owned by the Memorial Library of Music at Stanford University. This score was likely used for the early private performance at Joachim’s school, and for the preparation of the first published edition. It can be viewed at the library’s website: https://library.stanford.edu/news/johannes-brahms-tragic-overture-op-81

—©Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Ball State University