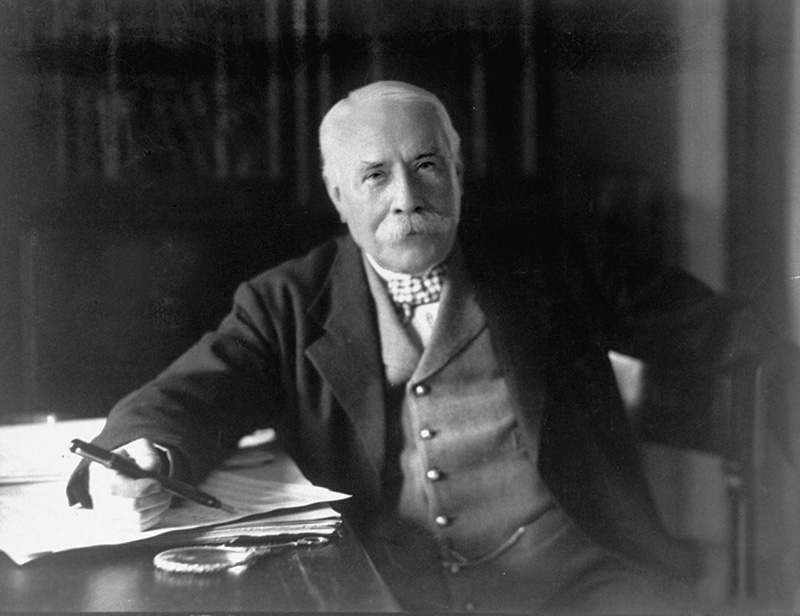

Edward Elgar

Born: June 2, 1857, Broadheath, U.K.

Died: February 23, 1934, Worcester, U.K.

Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E Minor, Op.85

- Composed: 1918

- Premiere: October 27, 1919, London, Edward Elgar conducting the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, Felix Salmond, cello

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: November 1970, Erich Kunzel conducting; Jacqueline du Pré, cello.

- Most Recent: March 2022, David Danzmayr conducting; Alban Gerhardt, cello.

- Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings

- Duration: approx. 30 minutes

In her 1924 essay Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown, Virginia Woolf wrote, “On or about December 1910 human nature changed.” She continued with an equally iconoclastic assertion: “All human relations shifted and when human relations change there is at the same time a change in religion, conduct, politics, and literature.” Although Woolf surely intended this statement as hyperbole and had no particular interest in music, the year 1910 did in fact mark a significant change in British musical aesthetics. On September 6, 1910, a concert in Gloucester Cathedral during the Three Choirs Festival featured Sir Edward Elgar’s mystical post-Wagnerian oratorio The Dream of Gerontius (1900). It was preceded by a radical new work for string orchestra that combined Tudor church music with avant-garde French impressionism, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. This premiere, though notable in retrospect, did not immediately loosen Elgar’s hold on British musical life. On November 10, when Elgar conducted violinist Fritz Kreisler and the Queen’s Hall Orchestra in the triumphant premiere of his Violin Concerto, Op. 61, one critic reported that “the huge audience went wild with pride and delight.”

However, the sea change in British musical aesthetics was evident by May 24, 1911, when Elgar conducted the premiere of his Second Symphony, Op. 63. Although dedicated to the memory of King Edward VII, who had died the previous year, the symphony was performed to a sparse and unenthusiastic audience in Queen’s Hall. Walking off the platform, Elgar exclaimed to concertmaster W.H. Reed: “What is the matter with them, Billy? They sit there like a lot of stuffed pigs.” That same year, suffering from delusions of grandeur, Elgar moved from the West Midlands to a lavish house in London that he could not afford to maintain. This miscalculation was exacerbated by the start of World War I in 1914. The war sent Elgar into a deep depression made worse by a loss of income, as British concert life was catastrophically affected.

Indeed, Elgar’s health also began to suffer. In 1916, he experienced a severe episode of vertigo due to Ménière’s disease; two years later he was operated on for tonsillitis. Returning home after surgery, he sketched a haunting theme in E minor. In May of that year, Elgar and his wife, Alice, returned to an isolated thatched-roof cottage in West Sussex that they had first rented in 1917. For the next two years, Elgar returned to that humble dwelling, called “Brinkwells,” during the warmer months. There he completed three chamber music scores in rapid succession: a violin sonata in E minor, Op. 82 (1918), a string quartet, also in E minor, Op. 83 (1918), and a piano quintet in A minor, Op. 84 (1919). Returning to the haunting theme that he had sketched after his tonsillitis operation, Elgar used it in the first movement of his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E Minor, Op. 85. These four scores, all cast in minor keys, are permeated with a sense of melancholic loss. As Brinkwells is very close to the English Channel, Elgar heard echoes of the war’s final titanic battles from northern France as he composed the cello concerto in 1918.

Unfortunately, the premiere of the cello concerto, which Elgar conducted in London’s Queen’s Hall on October 27, 1919, was unsuccessful. The soloist, Felix Salmond, was a fine cellist for chamber and orchestral music, but he was not a soloist and lost his nerve during the performance. In addition, the concerto itself was under-rehearsed. Albert Coates, the ambitious young conductor with whom Elgar shared the program, had taken much more than his allotted rehearsal time. That such an appalling incident happened at all testifies to how rapidly Elgar’s music had fallen out of favor. The press notices were coldly polite at best and sneering at worst. At the time, it must have seemed as if the concerto would sink into desuetude. However, Elgar was fortunate that a charismatic young British cellist, Beatrice Harrison, resolutely learned the work and promoted it. Her performances were highly successful and the score was reevaluated. Not long after, she recorded it with Elgar conducting. As a result of Harrison’s advocacy, the cello concerto remained at the heart of the instrument’s repertory even after much of Elgar’s music fell into obscurity after his death in 1934.

Indeed, Elgar’s cello concerto is now so famous that it is difficult to comprehend how innovative it must have seemed to those first listeners in 1919. Unlike his opulent violin concerto, Elgar’s cello concerto is concise, at times almost terse; the texture is lean rather than sumptuous; the orchestration rich but muted; and the formal design is almost startlingly original compared to the cello concertos of Dvořák and Lalo. As Elgar’s biographer Diana McVeagh exclaimed, “Is there another concerto with such a strange start?” She further observes that “the whole work is braced by the opening commanding double-stopped recitative for the soloist.”

After this dramatic gesture, the movement continues with the undulating first theme that Elgar had composed after his tonsillitis operation. Unlike many examples of sonata form, the wistful second theme does not provide a pronounced contrast: the music rises and falls on waves of emotion, ascending to passages of intensity and then falling back into introspection. The opening recitative returns at the end of the movement, played pizzicato by the soloist. This somber recall of the concerto’s beginning transitions into a quicksilver scherzo in G major that demands virtuosic control from the cellist. The adagio that follows, cast in the distant key of B-flat major, is a heartrending “song without words” made up of only 60 measures of music. In the finale, after a brusque opening, the dramatic recitative with which the concerto commenced returns, marked with Elgar’s characteristic direction of nobilmente. It is followed by the swaggering main theme in the movement’s modified rondo form. However, every restatement of this confident main theme is varied, and after a certain point it becomes less confident, less assured, and finally descends into grief. The music ebbs into a slower tempo, marked poco più lento. During this extended passage themes heard earlier are transformed into a lament. This searing passage is followed by a grandiloquent return of the soloist’s opening recitative, but this is abruptly brushed aside by a coda that hurtles toward the concerto’s defiant final cadence.

—© 2025 Byron Adams, Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Musicology University of California, Riverside