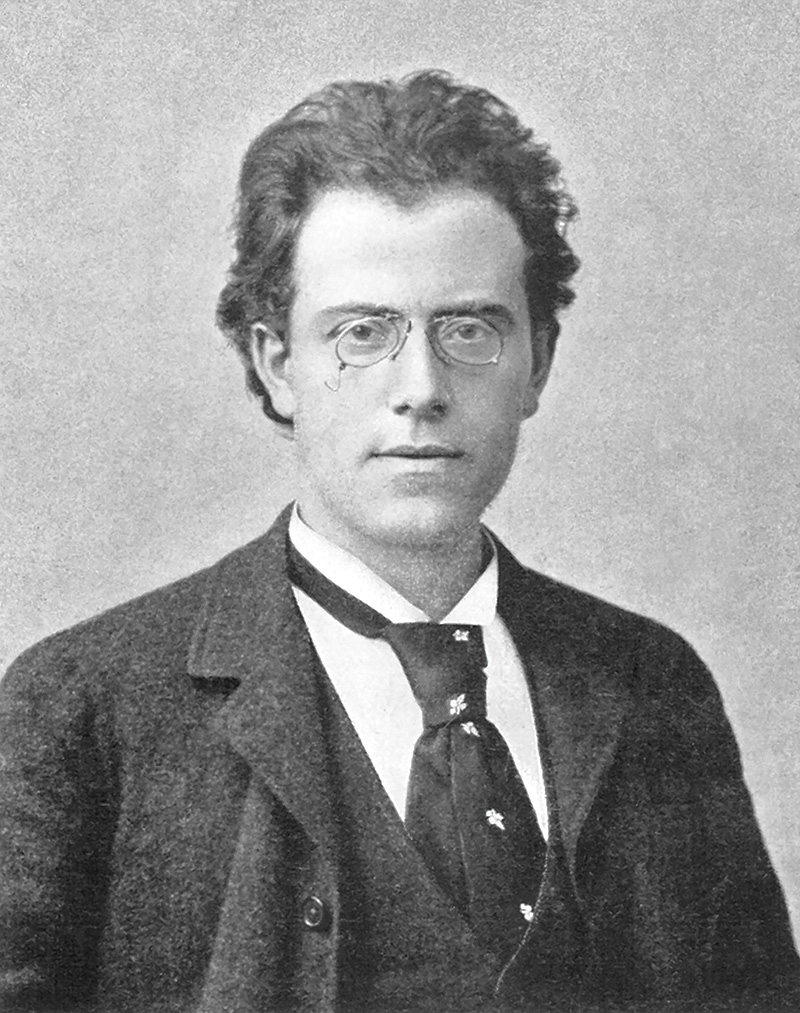

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, Kalist, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, Vienna, Austria

Rückert-Lieder

- Composed: 1901–02

- Premiere: January 29, 1905, Vienna, conducted by the composer with baritone Friedrich Weidemann as soloist

- Instrumentation: soprano solo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, oboe d’amore, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, harp, celeste, piano, strings

- CSO Notable Performances: First: April 1976, Henry Lewis conducting; Marilyn Horne, mezzo-soprano. Most Recent: April 1991, Jesús López-Cobos conducting; Andreas Schmidt, baritone. Recording: November 1991, Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer, Kindertotenlieder, Jesús López-Cobos conducting; Andreas Schmidt, baritone.

- Duration: approx. 20 minutes

Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) was Professor of Oriental Literature at Erlangen and Privy Counselor for King Friedrich Wilhelm IV at Berlin from 1841 to 1848. (Felix Mendelssohn was Kapellmeister at the German court at the same time; he wrote his incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the Royal Theater in 1842.) Rückert was known as both a productive scholar, with many translations of texts from Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, Armenian, Ethiopian, Coptic and Sanskrit, as well as a prolific writer of poems, many of which were influenced by the forms, images and content of Asian verses. His poems, which appeared in many periodicals, anthologies and collections during his lifetime, were popular and highly regarded, and they inspired musical settings from a number of 19th-century composers, including Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Heinrich Marschner and Henry Litolff.

Among the most notable of Rückert’s thousands of poems were the 428 verses collectively titled Kindertotenlieder — “Songs on the Death of Children” — that he wrote in 1832–1834 to assuage his grief over the death of his infant son; they were published only posthumously, in 1872. Gustav Mahler came to know the Kindertotenlieder through his extensive readings in German philosophy and literature, and they appealed to him not only for the expressive quality of their poetic images and the refinement of their language and structure, but also for their first-person viewpoint, the revelatory expression of self that he believed was the dynamic force driving artistic expression. (“Only when I experience do I compose — only when I compose do I experience,” was his life-long dictum.) When Anton Webern asked him in 1905 about his attraction to Rückert’s poems after having been immersed for many years in the folkish verses of Des Knaben Wunderhorn ("The Youth's Magic Horn"), Mahler replied, “After Wunderhorn, Rückert was the only thing I could do — this is poetry at first-hand; all other poetry is second-hand.”

In the summer of 1901, when he escaped from the pressures of directing the Vienna Court Opera to his country retreat at the village of Maiernigg on the Wörthersee in Carinthia, Mahler made orchestral settings of six of Rückert’s poems, three of which were from the Kindertotenlieder. Three years later, he added two more settings to the Kindertotenlieder cycle, which has remained one of his most esteemed works. Mahler did not regard the other three Rückert settings of 1901 — Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder, Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft and Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen — as a unified cycle, though their texts, which evoke love, nature and philosophical resignation, are related in the gentle contrast that they provide to the tragedy of the Kindertotenlieder. The following summer, after he had met and married the talented and beautiful Alma Schindler, he appropriated two more Rückert poems for musical treatment — Um Mitternacht and Liebst du um Schönheit.

In her reminiscences of Mahler, Alma recorded a delightful tale about Liebst du um Schönheit, which her husband wrote to celebrate their love and new life together: “I used to play Wagner a lot, and this gave Mahler the idea for a charming surprise. He had composed for me the only love-song he ever wrote — Liebst du um Schönheit — and he slipped it between the pages of Die Walküre. Then he waited day after day for me to find it; but I never happened to open the volume, and his patience gave out. ‘I think I’ll take a look at the Walküre today,’ he said abruptly. He opened it, and the song fell out. I was overwhelmed with joy, and we played it that day twenty times at least.”

“The very text of Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder (‘Do not look at my songs’),” according to the composer’s close friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner, “is so characteristic of Mahler that he might have written it himself.” Its mood is playful and tinged with humor.

Rückert wrote Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft (“I breathed a gentle fragrance”) when his wife decorated his desk with a lime-tree branch for his birthday. (The text plays on the pun of the German words Linde [“lime-tree”] and linde [“gentle”].) Mahler’s caressing treatment captures perfectly the poem’s sweetness and affirmation of love.

Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen (“I have lost touch with the world”), which the composer told Bauer-Lechner represented himself, is both a vocal analogue to the transcendent introspection of the Adagietto of the Fifth Symphony, on which Mahler was also engaged in 1902, and a preview of the resigned, peaceful acceptance that closes both the Ninth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde. This movement limns an ineffable elegiac emotion that Mahler was capable of expressing better than any other composer; it may well be the finest symphonic song that he ever wrote.

Um Mitternacht (“At Midnight”), scored for full complement of winds but without strings, is one of the most dramatic of Mahler’s creations. A nighttime uneasiness dominates much of the music, which is haunted by a starkly eerie scale descending into the most subterranean reaches of the ensemble. The mood brightens for the closing stanza, the brass is marshaled, and the song ends in sun-bright affirmation as poet and composer entrust themselves to God’s care.

Liebst du um Schönheit (“If you love for beauty”), Mahler’s paean to his marital love at the beginning of what proved to be the happiest period of his life, is rapturously lyrical and glowingly optimistic.

—©Dr. Richard E. Rodda