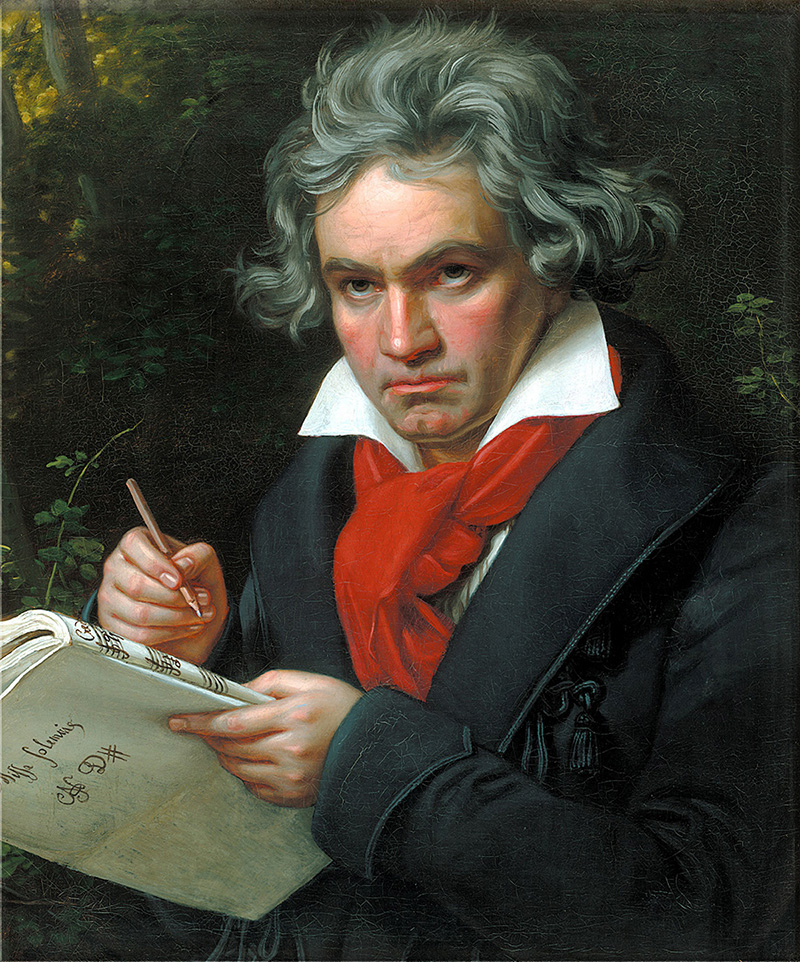

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: baptized December 17, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 19

- Composed: 1787–1801

- Premiere: March 29, 1795, Vienna Burgtheater, Beethoven was pianist and conductor

- Instrumentation: solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: January 1950, Thor Johnson conducting and William Kapell, piano. Most Recent: September 2021 as part of MusicNOW, Louis Langrée conducting and Daniil Trifonov, piano

- Duration: approx. 28 minutes

Beethoven is often hailed as a genius, but his masterworks did not always emerge effortlessly, as the long genesis of his Second Piano Concerto (Op. 19) attests. He began sketching the concerto during the late 1780s, yet he did not publish the score until 1801. When he started the concerto, at around 16 years of age, he was just beginning his career in his hometown of Bonn, Germany. By the time he published the score, he was an acclaimed composer and virtuoso pianist living in Vienna, Austria, where he had settled in 1792. Like most of Beethoven’s other piano concertos, the Second Concerto was composed primarily for his own performances.

Beethoven’s creative process usually involved a series of stages, during which he often produced numerous sketches for specific passages as well as for entire movements. Initially, he jotted down a few melodic fragments, without any further context. Once he had an idea of the large-scale structure, he created an outline of all the main ideas of a movement in the order they would likely be stated and varied. When satisfied with this sketch, he fleshed out all the details, including the orchestral parts. At each stage he routinely discarded ideas and inserted new ones. The resulting manuscripts are often quite messy, riddled with cross-outs and ink blots that conceal rejected passages. Compounding the challenge, he frequently worked on multiple compositions simultaneously.

By 1792, when he left Bonn, Beethoven had made significant progress on the concerto and had started working on the orchestral parts. At this stage, as was typical, he did not write out all of the piano part, since he intended to perform it himself and he could do so from memory. In Vienna, many of Beethoven’s performances took place in the palaces and homes of the nobility, some of whom had their own orchestras. Scholars believe that a performance of the Second Concerto likely took place in 1794 at one such private event. Nevertheless, Beethoven continued to revise the work, and, during late 1794 to early 1795, he replaced the second and third movements. Then he sketched ideas for the first movement’s cadenza, possibly because he planned to perform the work later in 1795. More revisions followed in 1798, when he conducted the latest version and performed the solo piano part in Prague. (Mozart also conducted his concertos from the keyboard.)

During the 19th century, pianist/composers like Beethoven delayed publishing their concertos because these works were part of their brand and they wanted to prevent rivals from performing them. Beethoven held back Op. 19 until 1801, releasing it a few months after the publication of the First Piano Concerto (Op. 15), which he wrote during some of the same years he was working on Op. 19. Only at this point was the piano part of Op. 19 fully notated. Nevertheless, Beethoven did not write out a cadenza for the first movement until 1809, by which time deafness had ended his performance career and other pianists were playing the work.

As a young composer, Beethoven carefully studied the compositions of Mozart and Haydn, and traces of Mozart’s style can be heard in the Second Piano Concerto, particularly in the size of the orchestra and some of the graceful melodic turns. Yet his emerging individuality is unmistakable. This is clearly heard in the dramatic orchestral outbursts in the opening minutes of the concerto’s first movement and in the numerous abrupt shifts in dynamic level in the following sections. Like Mozart, he treated the form of the first movement with flexibility. Traditionally, the opening orchestral section of a concerto presents all the main themes and then the solo piano joins the orchestra in a varied restatement of the themes. In this work, however, the orchestra presents two main themes, but then the piano enters with an entirely new, soft theme that gradually works up to the stronger, march-like original first theme. Beethoven then inserted numerous new phrases designed to show off the pianist’s technique. This section also features a new melody rather than restating the orchestra’s second theme (something that Mozart also occasionally did). During the movement’s last section, Beethoven combined a recollection of the forceful orchestral opening with material from the piano’s first section. The excitement of the movement is created by the contrast between playful ideas and orchestral phrases tinged with drama.

The second movement opens with a quiet orchestral theme. Then the piano takes over, ornamenting and spinning out the tender melody while retaining its soft dynamic level. Occasionally, the orchestra punctuates the piano’s phrases or provides a loud restatement of the melody, but otherwise the movement is largely a showcase for the piano. Whereas some of the melodic ornaments might remind us of Mozart, there are two highly unusual passages that are entirely Beethoven’s style. The first occurs during the middle of the movement when the oboes quietly intone the melody. The accompaniment for this passage is quite unusual: the lower winds sustain chords, while the strings have soft, detached chords, and the piano repeats soft, short, two-note figures. The other unusual passage occurs toward the end of the movement when the pianist plays a long, mostly unaccompanied, pensive melody that is marked con gran espressione (with great expression). The orchestra then closes the movement with a hushed farewell, without the piano.

In contrast to the meditative atmosphere of the slow movement, the concluding one is a rollicking Rondo. The piano introduces the recurring playful theme, setting the tone for a movement brimming with joy and exuberance. Occasional pauses recall the drama of the first movement, but the prevailing mood remains buoyant. In a characteristic twist, Beethoven lets the piano end with a few detached soft chords, leaving the orchestra to deliver a loud, hearty conclusion to the work.

Despite its protracted genesis and revisions across a decade, Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto feels unified, its youthful energy balanced with emerging originality. Nowhere in the music is there any sign of the struggles that shaped the concerto, only the vibrant voice of a composer already on the path to greatness.

—©Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Ball State University