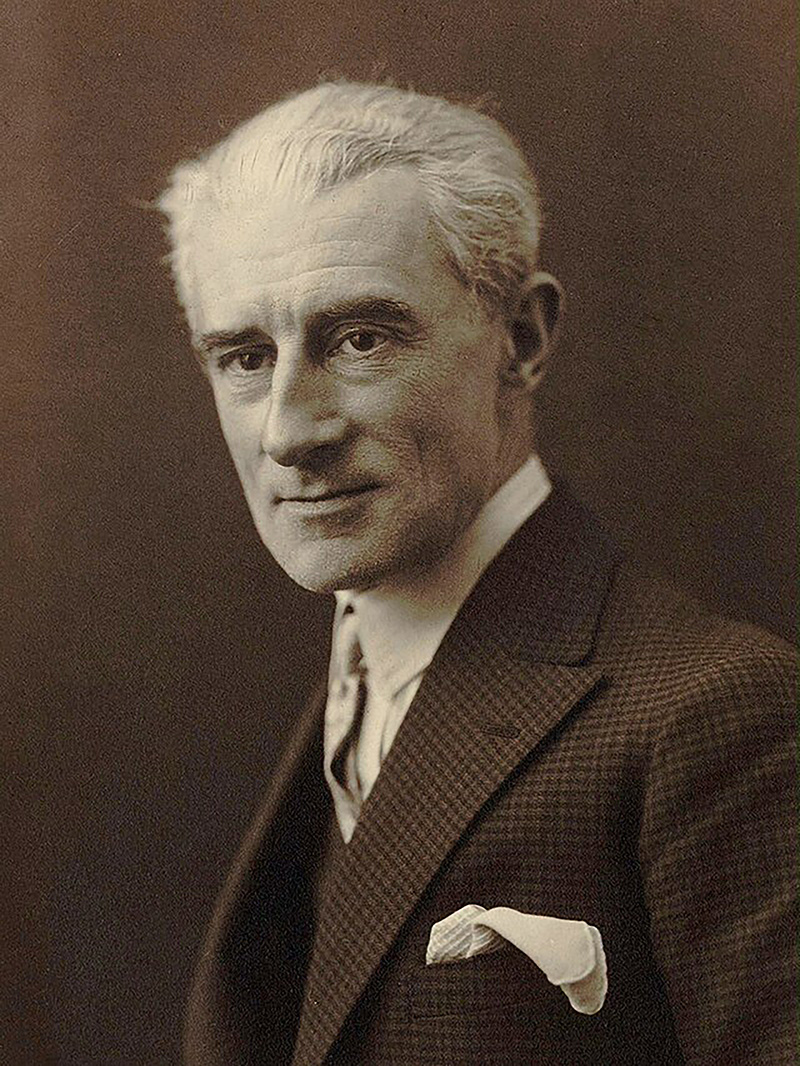

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, Paris, France

Piano Trio in A Minor

- Composed: 1914

- Premiere: January, 1915, Paris, with Gabriel Willaume, violin; Louis Feuillard, cello; and Alfredo Casella, piano

- Duration: approx. 26 minutes

The Parisian musical world in the late 19th century was a political minefield, polarized between conservative and avant-garde elements and shaped by three distinct forces: the music societies, the conservatories and French music journalism. And though Gabriel Fauré would have preferred invisibility, he ended up as a figurehead for all three: as president of both the conservative nationalist Société nationale de musique and the progressive Société musicale indépendente, as director of the Conservatoire de Paris and as music critic for Le Figaro.

His appointment to the Conservatoire in 1905 had provoked outrage among the most vocal political factions. Not only had he never studied at the Conservatoire himself, but his views on music were notoriously liberal. He enjoyed the esteem of a small group of connoisseurs but, although performances of his works had been fêted in the private salons of the Parisien aristocracy, his music was too modern for the general public, for whom even Wagner was deemed too progressive. During Fauré’s tenure, the reforms he introduced to the academic curriculum were sensible: required courses in music history and harmony, chamber music and large-ensemble training, and a broadened repertoire that extended beyond the war horses of the old masters. He also imposed personnel policies, to avoid professional conflicts of interest and diffuse undercurrents of favoritism. Yet, the daily battles with colleagues had become tiresome, and he grew to resent the distraction from his composing.

By 1919, after running the institution for 14 years, Fauré was exhausted. His health had become poor due to a lifetime of heavy smoking, and, moreover, he was suffering a peculiar kind of hearing loss that distorted pitches in the extreme low and high ranges. When political tides turned and the government requested his resignation from the Conservatoire, he felt a sense of relief. He withdrew to spend the summer with his mistress, Marguerite Hasselmans, in Annecy-le-Vieux in a large and peaceful country house overlooking the valley and the lake beyond, from which he wrote to his wife, Marie, “

Maurice Ravel expected to die fighting for France in World War I. In early 1914, before volunteering in the military, he put his affairs in order and began working furiously to complete his Trio for piano, violin and cello “with the sureness and lucidity of a madman.” Enlisting had become something of an obsession for the composer. At age 20, he had been exempted from conscription due to poor health. He had applied to the Air Force and had been turned away. By 1914, at age 39, Ravel noted that his brother and his friends were already serving, so he doubled down on his efforts. Following continued rejections due to his low weight and his weak heart, he pulled strings to secure a post as a truck driver on the front lines.

In a letter dated September 8, 1914, to Ida Godebska, a Parisian patron, he described his efforts to dummy-proof the score to his Piano Trio for publication after his death:

Before going to Bayonne I spent a month working from morning till night, without even taking the time to bathe in the sea. I wanted to finish my Trio, which I have treated as a posthumous work. That does not mean that I have lavished genius on it, but rather, that the order of my manuscript and of the notes regarding it will allow anyone else to correct the proofs.

Ravel did not produce a great deal of chamber music, but a decade before the Piano Trio he had composed several gems that still shine among the early 20th-century repertoire. His extraordinary string quartet and his otherworldly Introduction et Allegro for harp, flute, clarinet and string quartet marked an abrupt break from the Teutonic angst that had dominated the late 19th-century Romantic tradition.

However, in composing his Piano Trio, he used a different approach from those earlier works: he mapped out the overall structure and harmonic schema first before composing a single melody, famously commenting to his friend and pupil, Maurice Delage, "My Trio is finished. I only need the tunes for it."

Ravel’s letters in the months leading up to the completion of the work are littered with breadcrumbs that map the steps of his creative process. In March, he wrote to Mme. Hélène Casella, "I am working on the Trio despite the cold and stormy weather, rain, and hail." In early July, he revealed his writer’s block: "In spite of the fine weather, for the last three weeks the Trio has made no progress, and I'm disgusted with it.” Later that month he informed his publisher, Jacques Durand, “I am continuing to work, still rather slowly it is true, but more surely. I am counting on the participation of the weather, which is turning fair again.” In early August, when France had officially entered the war, he reported a creative burst to Cipa Godebsky, "I have never worked with more insane, more heroic intensity." Finally, in late September, he wrote to Igor Stravinsky with good news about both the Piano Trio and his efforts to join the military: “I haven't been so lucky; they don't want me, but I am pinning my hopes on the new medical examination that everyone who has been rejected will have to pass, and on the strings I may be able to pull. … The idea that I should be leaving at once has made me complete five months' work in five weeks! My Trio is finished.”

The completed work reveals Ravel’s desire to honor traditional forms while reaching for new sonorities, novel colors and original textures. The first movement opens with a classical sonata form that stands at odds with an exoticism in its harmonies, which Ravel described as “Basque in color.” The asymmetrical 3+2+3 syncopation that pervades the movement suggests the zortziko, a Euskadi dance accompaniment for folksongs such as the one hinted at in the opening string melody. The composer uses tonal space to cast an ethereal haze over the movement: the violin and cello are set octaves apart with the piano suspended between them, while the dialogue that springs up among the three instruments is alternately passionate, intimate and stark. Ravel hides his craft while drawing attention to his art: he blurs the structural lines of the movement by twice taunting the listener with a false recapitulation of the opening before finally allowing the rhythm to dissolve as the music drifts to a tender conclusion.

The second movement is a scherzo in all but name. The eccentric title “Pantoum” is a literary reference to a form of Malaysian poetry that French poets such as Paul Verlaine and Charles Baudelaire popularized, in which the second and fourth lines of poetry reappear as the first and third lines of the subsequent stanza. Ravel’s ordering and repetition of musical phrases suggest a similar outline. Three different tunes form the architecture of a classical scherzo and trio using a variety of textures that invoke his earlier string quartet, including right- and left-hand pizzicato, glissandos and brisk arpeggios. The rhythms of the trio section are particularly disorienting to the ear: while the strings play quick five-note groups, the piano plays against them first in slow four-note groups, then in moderate groups of three.

The third movement is both haunting and haunted; a lament with a gravitas that suggests a eulogy. Titled Passacaille, it represents the French counterpart to the Italian passacaglia, a Baroque structure in which the tune sits above a repeating bass line and shifts keys and tonalities as it unfolds. In Ravel’s hands, the bass of the piano boils over into an angst that borders on rage, before settling back into remorse and then oblivion.

The final movement opens with an exotic splash of tremolos and string harmonics accompanying a piano strain, colored in parallel fifths and double octaves, that suggests pentatonicism. Here too, the composer leaves the listener lost in rhythmic complexities, as the meter of the music vacillates between five and seven. Its primary theme invokes the Basque folk tunes of Ravel’s home region, building to a final, triumphant blast of euphoria.

In the year 1914, Maurice Ravel was hardly concerned with creating a magnum opus (as he famously commented, "I have written only one masterpiece. That is the Boléro. Unfortunately, it contains no music.") But the emotional range and expressive depth of his Piano Trio, whose publication he did not expect to live long enough to witness, is remarkable. In it, Ravel successfully balances the sensuality of shimmering colors and undulating textures with time-honored musical architecture to create a masterwork that was presciently neoclassical, but also unambiguously French.

©Dr. Scot Buzza