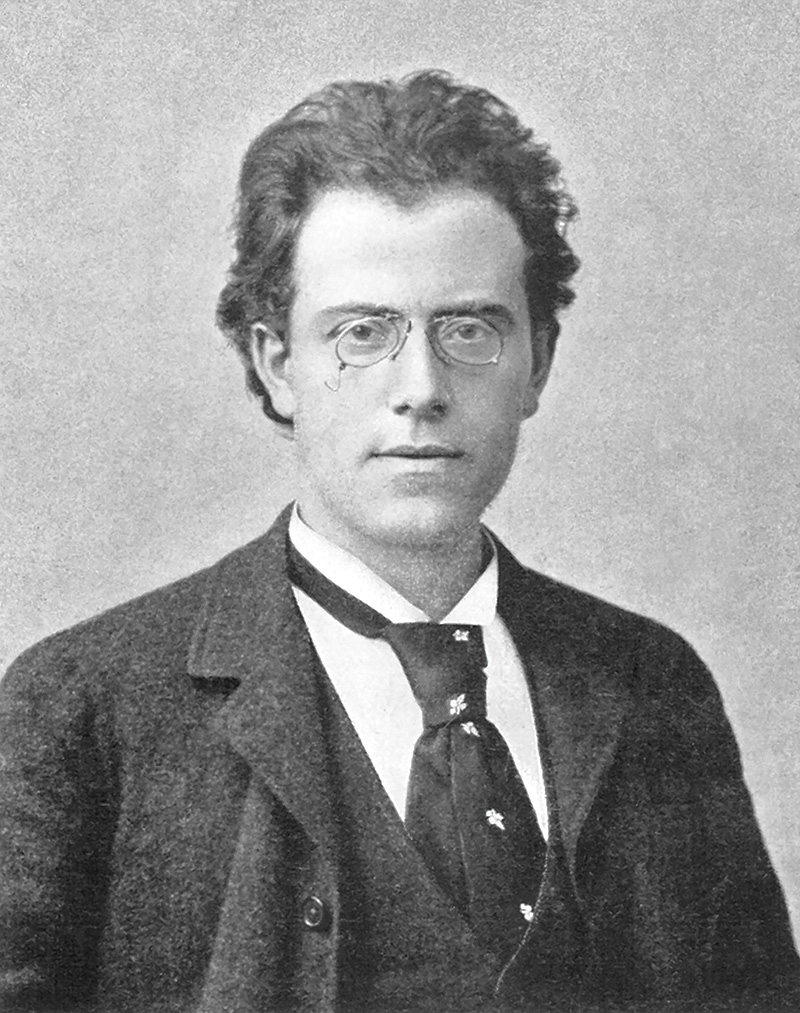

Gustav Mahler

- Born: July 7, 1860 in Kalischt, Bohemia

- Died: May 18, 1911 in Vienna

Symphony No. 2, Resurrection

- Composed: 1888–1894

- Premiere: Mahler conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in the work’s first three movements on March 4, 1895 at a performance arranged by Richard Strauss, who was then that ensemble’s Music Director. Mahler returned to Berlin to lead the first complete performance later that year, on December 13. He also directed the American premiere, on December 8, 1908, with the orchestra of the Symphony Society of New York at Carnegie Hall.

- Instrumentation: Soprano and mezzo-soprano soloists, SATB chorus, 4 flutes (incl. 4 piccolos), 4 oboes (incl. 2 English horns), 5 clarinets (incl. bass clarinet, 2 E-flat clarinets), 4 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), 10 horns, 8 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, 2 timpani, bass drum, chimes, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, rute, 3 snare drums, suspended cymbals, 2 tam-tams, 3 triangles, 2 harps, organ, strings

- CSO notable performances: First Performance: November 1928 Fritz Reiner, conductor; Iliah Clark, soprano; Mme. Charles Cahier, mezzo-soprano; May Festival Chorus—for a special concert by the newly established Cincinnati Institute of Fine Arts, which would later become ArtsWave. Most Recent: October 2008 Gilbert Kaplan, conductor; Janice Chandler, soprano; Christianne Stotijn, mezzo-soprano; May Festival Chorus, Robert Porco, director

- Duration: approx. 80 minutes

In August 1886, the distinguished conductor Arthur Nikisch, later music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, appointed the 26-year-old Gustav Mahler as his assistant at the Leipzig Opera. At Leipzig, Mahler met Carl von Weber, grandson of the celebrated composer Carl Maria von Weber, and the two worked on a new performing edition of the virtually forgotten Weber opera Die drei Pintos (“The Three Pintos,” two being impostors of the title character). (In an episode that bore on the composition of the First Symphony, Mahler, always subject to intense emotional turmoil, fell in love with Carl’s wife during his frequent visits to the Weber house. The lovers planned to run away together, but at the decisive moment she left Mahler stranded, quite literally, at the train station.) Following the premiere of Die drei Pintos, on January 20, 1888, Mahler attended a reception in a room filled with flowers. That seemingly beneficent image played on his mind, becoming transmogrified into nightmares and waking visions, almost hallucinations, of himself on a funeral bier surrounded by floral wreaths.

The First Symphony was completed in March 1888, and its successor was begun almost immediately. Mahler, spurred by the startling visions of his own death, conceived the new work as a tone poem titled Totenfeier (“Funeral Rite”). The title was apparently taken from the translation by the composer’s close friend Siegfried Lipiner, titled Totenfeier, of Adam Mickiewicz’s Polish epic Dziady, which appeared just as work on the tone poem was begun. Though Mahler inscribed his manuscript “Symphony in C minor/First Movement,” he had no clear idea at the time what sort of music would follow Totenfeier, and he considered allowing the movement to stand as an independent composition. He completed and dated the orchestral score of the movement on September 10, 1888 in Prague, where he was conducting performances of Die drei Pintos at the German Theater.

The next five years were ones of intense professional and personal activity for Mahler. He resigned from the Leipzig Opera in May 1888 and applied for posts in Karlsruhe, Budapest, Hamburg and Meiningen. To support his petition for this last position, he wrote to Hans von Bülow, director at Meiningen until 1885, to ask for his recommendation, but the letter was ignored. Richard Strauss, however, the successor to Bülow at Meiningen, took up Mahler’s cause on the evidence of his talent furnished by Die drei Pintos and his growing reputation as a conductor of Mozart and Wagner. When Strauss showed Bülow the score for the Weber/Mahler opera, Bülow responded caustically, “Be it Weberei or Mahlerei [puns in German on “weaving” and “painting”], it makes no difference to me. The whole thing is a pastiche, an infamous, out-of-date bagatelle. I am simply nauseated.” Mahler, needless to say, did not get the job at Meiningen, but he was awarded the position at Budapest, where his duties began in October 1888.

During 1889, both of Mahler’s parents died—his father in February, his mother just eight months later—so the responsibility for supporting his brothers and sisters fell upon him. A ne’er-do-well brother, Alois, fled to America. Gustav moved Emma and Otto from their home in Bohemia to Vienna, where they could all be close to their sister, Leopoldine, who had previously married and settled in the Habsburg capital. Justine went to Budapest to keep house for her brother. But this time of grief held yet one more shock, when Leopoldine fell gravely ill with a brain tumor and died late in the year.

In 1891, Mahler switched jobs once again, this time leaving Budapest to join the prestigious Hamburg Opera as principal conductor. There he encountered Bülow, who was director of the Hamburg Philharmonic concerts. Bülow had certainly not forgotten his earlier low estimate of Mahler the composer, but after a performance of Siegfried he allowed that “Hamburg has now acquired a simply first-rate opera conductor in Mr. Gustav Mahler...who equals in my opinion the very best.” Encouraged by Bülow’s admiration of his conducting, Mahler asked for his comments on the still unperformed Totenfeier. Mahler described their September 15th encounter:

When I played my Totenfeier for Bülow, he fell into a state of extreme nervous tension, clapped his hands over his ears and exclaimed, “Beside your music, Tristan sounds as simple as a Haydn symphony! If that is still music then I do not understand a single thing about music!” We parted from each other in complete friendship, I, however, with the conviction that Bülow considers me an able conductor but absolutely hopeless as a composer.

Mahler, who throughout his career considered his composition more important than his conducting, was deeply wounded by this behavior, but he controlled his anger out of respect for Bülow, who had extended him many kindnesses and become something of a mentor. Bülow did nothing to quell his doubts about the quality of his creative work, however, and Mahler, who had written nothing since Totenfeier three years before, was at a crisis in his career as a composer.

The year after Bülow’s withering criticisms, Mahler found inspiration to compose again in a collection of German folk poems by Ludwig Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano called Des Knaben Wunderhorn (“The Youth’s Magic Horn”). He had known these texts since at least 1887, and in 1892 set four of them for voice and piano, thereby renewing some of his creative self-confidence. The following summer, when he was free from the pressures of conducting, he took rustic lodgings in the village of Steinbach on Lake Attersee in the lovely Austrian Salzkammergut, near Salzburg, and it was there that he resumed work on the Second Symphony, five years after the first movement had been completed. Without a clear plan as to how they would fit into the Symphony’s overall structure, he used two of the Wunderhorn songs from the preceding year as the bases for the internal movements of the piece. On July 16 he completed the orchestral score of the Scherzo, derived from Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt, a cynical poem about St. Anthony preaching a sermon to the fishes, who, like some human congregations, return to their fleshly ways as soon as the holy man finishes his homily. Only three days later, Urlicht (“Primal Light”) for contralto solo, was completed; by the end of the month, the Andante, newly conceived, was finished.

Mahler composed with such frenzy that summer that his sisters almost urged him to give up his work lest his health be ruined. Natalie Bauer-Lechner, a close friend who left a revealing book of personal reminiscences of the composer, related that he looked strained and drawn and was “in an almost pathological state” at Steinbach. “Don’t talk to me of not looking well,” he reprimanded. “Don’t ever speak to me of this while I am working unless you want to make me terribly angry. While one has something to say, do you think that one can spare oneself? Even if it means devoting one’s last breath and final drop of blood, one must express it.”

By the end of summer 1893, the first four movements of the Symphony were finished but Mahler was still unsure about the work’s ending. The finality implied by the opening movement’s “Funeral Rite” seemed to allow no logical progression to another point of climax. As a response to the questions posed by the first movement, he envisioned a grand choral close for the work, much in the manner of the triumphant ending of Beethoven’s last symphony. “When I conceive a great musical picture, I always arrive at a point where I must employ the ‘word’ as the bearer of my musical idea,” he confided. “My experience with the last movement of my Second Symphony was such that I literally ransacked world literature, even including the Bible, to find the redeeming word.” Still, no solution presented itself.

In December 1892, Bülow’s health gave out and he designated Mahler to be his successor as conductor of the Hamburg Philharmonic concerts. A year later Bülow went to Egypt for treatment, but died suddenly in Cairo on February 12, 1894. Mahler was deeply saddened by the news. He met with the Czech composer Josef Förster that day and played through the Totenfeier with such emotion that his colleague was convinced it was offered “in memory of Bülow.” Förster recalled the memorial service they had attended at Hamburg’s St. Michael Church:

Mahler and I were present at the moving farewell.... The strongest impression to remain was that of the singing of the children’s voices. The effect was created not just by Klopstock’s profound poem [Auferstehen—“Resurrection”] but by the innocence of the pure sounds issuing from the children’s throats. The hymn died away, and the old, huge bells of the church opened their eloquent mouths and their mighty threnody poured forth to the entire port city.

The funeral procession started. At the Hamburg Opera, where Bülow had so often delighted the townspeople, he was greeted by the funeral music from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung [conducted by Mahler]. A great moment, full of reverence, remembrance and thankfulness.

Outside the Opera, I could not find Mahler. But that afternoon I could not restrain my restlessness, and hurried to his apartment as if to obey a command. I opened the door and saw him sitting at his writing desk, his head lowered and his hand holding a pen over some manuscript paper. Mahler turned to me and said: “Dear friend, I have it!”

I understood. As if illuminated by a mysterious power I answered: “Auferstehen, ja auferstehen wirst du nach kurzen Schlaf.” [“Rise again, yes you will rise again after a short sleep.”] I had guessed the secret: Klopstock’s poem, which that morning we had heard from the mouths of children, was to be the basis for the closing movement of the Second Symphony.

On June 29, 1894, just three months later, Mahler completed his monumental “Resurrection” Symphony, six years after it was begun.

■ ■ ■

The great scope of the “Resurrection” Symphony, both in length and in performing forces, made its premiere a significant undertaking. Richard Strauss, then director of the Berlin Philharmonic (as successor to Bülow!), wanted to premiere the work, but he was unable to secure the vocal forces needed for the closing sections, so he arranged a performance of the first three movements for March 4, 1895 and invited Mahler to conduct. (Mahler was still reeling on that date from the suicide of his beloved younger brother Otto less than a month before. Mahler, subject to migraine headaches during times of great stress, was almost incapacitated by blinding headaches during the rehearsals and premiere.) Though the Symphony was performed as an incomplete torso, the audience approved it warmly, recalling the composer–conductor to the stage at least five times with its applause. The critics, however, vilified the new piece, ignoring the success it had gained with the public. When the complete work was presented on December 13, the critics again decried the score. (One representative comment scorned “the cynical impudence of this brutal and very latest music maker.”) Despite critical carping, the Second Symphony became Mahler’s most often heard work during his lifetime: the score was published in 1897, he chose it for his Viennese farewell performance in 1907, and it was the first of his works he conducted (on December 8, 1908 at Carnegie Hall with the New York Symphony Orchestra) after coming to America.

The composer himself wrote of the emotional engines driving the Second Symphony:

- 1st movement. We stand by the coffin of a well-loved person. His life, struggles, passions and aspirations once more, for the last time, pass before our mind’s eye.—And now in this moment of gravity and of emotion which convulses our deepest being, our heart is gripped by a dreadfully serious voice that always passes us by in the deafening bustle of daily life: What now? What is this life—and this death? Do we have an existence beyond it? Is all this only a confused dream, or do life and this death have a meaning?—And we must answer this question if we are to live on.

- 2nd movement—Andante (in the style of a Ländler). You must have attended the funeral of a person dear to you and then, perhaps, the picture of a happy hour long past arises in your mind like a ray of sun undimmed—and you can almost forget what has happened.

- 3rd movement—Scherzo, based on Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt. When you awaken from the nostalgic daydream [of the preceding movement] and you return to the confusion of real life, it can happen that the ceaseless motion, the senseless bustle of daily activity may strike you with horror. Then life can seem meaningless, a gruesome, ghostly spectacle, from which you may recoil with a cry of disgust!

- 4th movement—Urlicht (“Primal Light,” mezzo-soprano solo). The moving voice of naïve faith sounds in our ear: I am of God, and desire to return to God! God will give me a lamp, will light me to eternal bliss!

- 5th movement. We again confront all the dreadful questions and the mood of the end of the first movement. The end of all living things has come. The Last Judgment is announced and the ultimate terror of this Day of Days has arrived. The earth quakes, the graves burst open, the dead rise and stride hither in endless procession. Our senses fail us and all consciousness fades away at the approach of the eternal Spirit. The “Great Summons” resounds: the trumpets of the apocalypse call. Softly there sounds a choir of saints and heavenly creatures: “Rise again, yes, thou shalt rise again.” And the glory of God appears. All is still and blissful. And behold: there is no judgment; there are no sinners, no righteous ones, no great and no humble—there is no punishment and no reward! An almighty love shines through us with blessed knowing and being.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda