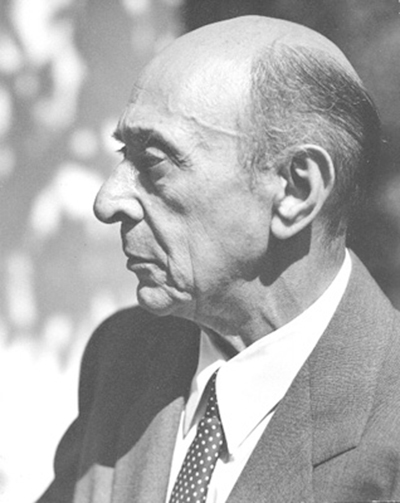

Arnold Schoenberg

Born: September 13, 1874, Vienna, Austria

Died: July 13, 1951, Brentwood, California

Verklärte Nacht (“Transfigured Night”), Op. 4

- Composed: Written for string sextet in 1899; scored for string orchestra in 1917, revised in 1943.

- Premiere: Sextet premiered March 15, 1902 in Vienna; orchestral version premiered on June 3, 1919 in Vienna, conducted by the composer.

- Instrumentation: strings

- CSO notable performances: First: March 1923, Fritz Reiner conducting. Most Recent: February 2013, Pinchas Zukerman conducting.

- Duration: approx. 32 minutes

At the age of 16, in 1890, Arnold Schoenberg decided to become a professional musician, having already dabbled in composition, taught himself to play the violin and cello, and participated in some chamber music concerts with his friends. His father’s death in 1889 had thrown him into rather serious financial distress, however, and he had to scratch out a livelihood after leaving school in 1891 by working in a bank and conducting local choruses and theater orchestras for a few schillings per performance. In 1893, he met Alexander Zemlinsky, who had already established a Viennese reputation as a composer, conductor and teacher, though he was only two years Schoenberg’s senior. Schoenberg showed his new friend some of his manuscripts, and Zemlinsky was so impressed with his talent that he offered to take him on as a counterpoint student (this instruction turned out to be Schoenberg’s only formal study) and secured him a position in the cello section of the Polyhymnia Orchestra to help earn a little money. Zemlinsky assumed the role of guardian to Schoenberg, introducing the young musician to his circle of professional colleagues and constantly offering advice and encouragement. In 1901, Schoenberg married Zemlinsky’s sister, Mathilde.

During the summer of 1899, Schoenberg and Zemlinsky were on holiday in the mountain village of Payerbach, south of Vienna, and it was there that Schoenberg began a work for string sextet based on a poem by Richard Dehmel: Verklärte Nacht (“Transfigured Night”), which had appeared three years earlier in a collection called Weib und Welt (“Woman and World”). (Schoenberg was familiar with Dehmel’s work by at least 1897, since he set several of the poet’s verses in that year.) Dehmel was one of the most distinguished German poets of the day, whose verses bridged the sensuous Impressionism of the preceding generation and the intense spirituality of encroaching Expressionism. Verklärte Nacht matches well the Viennese fin-de-siècle temperament, when Sigmund Freud was intellectualizing sex with his systematic explorations into the subconscious and Gustav Klimt was painting full-length portraits of his female subjects as he imagined they would look totally nude, before applying layers of elaborate, gold-sparkled costumes to finish the canvas. The following excerpt from Dehmel’s poem appears in Schoenberg’s printed score:

“Two people walk through the bare, cold woods; the moon runs along, they gaze at it. The moon runs over tall oaks, no cloudlet dulls the heavenly light into which the black peaks reach. A woman’s voice speaks:

“‘I bear a child, but not by you. I walk in sin alongside you. I sinned against myself mightily. I believed no longer in good fortune but still had mighty longing for a full life, mother’s joy and duty; then I grew shameless, then horror-stricken, I let my sex be taken by a stranger and even blessed myself for it. Now life has taken its revenge: Now I have met you, you.’

“She walks with clumsy gait. She gazes upward; the moon runs along. Her somber glance drowns in the light. A man’s voice speaks:

“‘The child that you conceived be to your soul no burden. Oh look, how clear the universe glitters! There is a glory around All, you drift with me on a cold sea, but a peculiar warmth sparkles from you in me, from me in you. It will transfigure the strange child you will bear for me, from me; you brought the glory into me, you made myself into a child.’

“He holds her around her strong hips. Their breath kisses in the air. Two people walk through the high, light night.”

Schoenberg glossed this richly emotional poem with music influenced by Wagner’s lush Tristan chromaticism, Brahms’ intellectual rigor and the intense expression of Romanticism to create a vast one-movement piece for pairs of violins, violas and cellos that is virtually a programmatic tone poem, one of the few such specimens in the chamber music literature. When the work was completed in December, Zemlinsky urged the Tonkünstler Society of Vienna to produce the first performance, “but,” he recorded in his memoirs, “I had no luck. The piece was given ‘a trial’ and the result was absolutely negative. One member of the jury gave his judgment in these words: ‘Why, that sounds as if someone had smudged up the score of Tristan while the ink was still wet!’” The official reason the committee gave for rejecting the score was a single harmony in the closing measures that it could not find in any textbook. However, the Berlin publisher Dreilinien thought highly enough of Verklärte Nacht to print it immediately in 1899, thus making it the earliest of Schoenberg’s published works. The work was finally presented on March 15, 1902, when the augmented Arnold Rosé Quartet premiered it under the auspices of the Tonkünstler Society (!). Schoenberg had already acquired a reputation as an unrepentant modernist, and the audience insisted on being put off by the music’s ripe harmony and the lubricity of its subject. The Hungarian violinist Francis Aranyi reported that the premiere was greeted “with much blowing of whistles, heaving of rotten eggs, etc.,” but that Rosé valiantly took his bows at the end “just as all hell broke loose.” Over a number of years, however, Verklärte Nacht came to be viewed not as an avant-garde aberration but as one of the foremost creations of the Post-Romantic era. When Dehmel first heard the work, in 1912 in Hamburg, he wrote Schoenberg a letter full of congratulations that ended with the lines:

O glorious sound! my words now ring,

in tones to God re-echoing;

To you this highest joy I owe;

On earth no higher may we know.

Near the end of his life, when Schoenberg was venerated (and vilified) as the patriarch of serialism and modernity, he looked back in the famous essay On revient toujours (“One Always Returns”) with an almost touching nostalgia to the music of his youth. “It was not given to me to continue writing in the style of Verklärte Nacht,” he explained. “Fate led me along a harder path. But the wish to return to the earlier style remained constantly with me.” Then, after admitting the undeniable influences of Wagner and Brahms on the piece, he continued, “Nevertheless, I do believe that a little bit of Schoenberg may also be found in it, particularly in the breadth of the melodies, in contrapuntal and motivic developments, and in the quasi-contrapuntal movement of harmonies and harmonic basses against the melody. Finally, there are even passages of indeterminate harmony, which doubtless may be seen as portents for the future.” He does not mention the mastery of mood and programmatic association he brought to this music, composed when he was only 25 years old.

Wrote Charles O’Connell of Verklärte Nacht, “Schoenberg’s musical version of the touching poem is singularly eloquent. The variety of expression, the really tremendous climaxes, the warmth and vigor and tenderness, the wonder of the transfiguration of love and forgiveness combine to provide an unforgettable musical experience. With rigid economy of means, he interprets musically the pain of guilt, the agony of confession, and the terror of punishment; the ageless mystery of gestation, the magnificence of self-denial, and the serene loveliness of understanding and compassion.”

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda