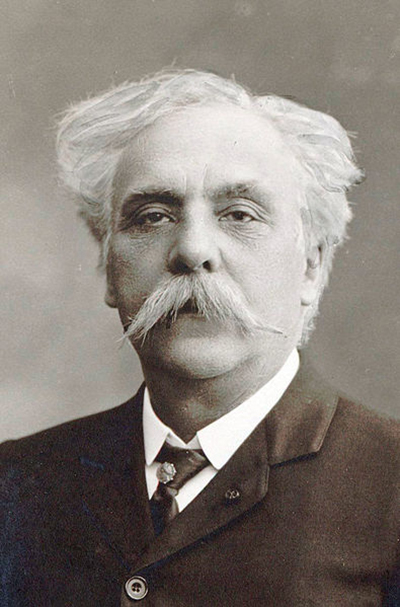

Gabriel Fauré

Born: May 12, 1845, Pamiers, Ariège, France

Died: November 14, 1924, Paris

Requiem, OP. 48

- Composed: 1887–1888, revised in 1893

- Premiere: January 16, 1888 in Paris, the composer conducting

- Instrumentation: SATB chorus, SB soloists, 2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, harp, organ, strings

- May Festival Notable Performances: First: May 1956, Josef Krips conducting the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra with Naomi Farr, soprano; Donald Gramm, bass-baritone; Christ Church Choir, Parvin Titus, choirmaster; and Westwood First Presbyterian Church Choir, Willis W. Beckett, choir director. Most Recent: May 2008, Robert Porco conducting the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra with Yulia Van Doren, soprano; Donnie Ray Albert, baritone; and the May Festival Chorus, Robert Porco, director.

- Duration: approx. 36 minutes

It is one of the ironies of music history that some of the greatest sacred works have been composed by men who cared little for religion. Mozart paid scant attention to the faith after he left Salzburg, preferring the humanistic philosophies of Freemasonry; Beethoven was a theist who thought conventional religion stifled full realization of the deity; Verdi refused to set foot in a church for any religious services, and would wait outside in a carriage for his wife on Sunday mornings; and Gabriel Fauré, though he held some of Paris’ most prestigious musical positions as a church organist and wrote one of the most perfect of all sacred compositions, was an avowed agnostic. Upon reading a manifesto of faith in an important Catholic journal, Fauré wrote, rather condescendingly, “How nice is this self-assurance! How nice is the naïveté, or the vanity, or the stupidity, or the bad faith of the people for whom this was written, printed and distributed.” Émile Vuillermoz, in his biography of the composer, explained that “only his natural courtesy and his professional conscience allowed him to carry out his duties as an organist with absolute correctness, and with the least amount of hypocrisy to write a certain number of religious works.... The Requiem is, if I dare say so, the work of a disbeliever who respects the beliefs of others.” Rather than a testament of dogmatic faith, then, Fauré’s Requiem is a work to console and comfort the living—music, according to Vuillermoz, “to accompany with contemplation and emotion a loved one to a final resting place.”

Fauré began his career as an organist and church musician in 1866 at Rennes and four years later went to Clignancourt, a suburb north of Paris. In 1871, he was appointed organist at the Church of Saint-Honoré Eylau, and in the following years became assistant to Widor at Saint-Sulpice and frequently substituted for Saint-Saëns at the Madeleine. When Saint-Saëns left that post in 1877 to give his full attention to composing and concertizing, he was succeeded by Théodore Dubois, who named Fauré as his assistant. Fauré became chief organist at the Madeleine in 1896, when Dubois assumed directorship of the Paris Conservatoire. Fauré had contributed an occasional piece of service music as part of his duties at various churches, but the Requiem was his first large-scale work in any form. He said that it was begun in 1887 “just for the pleasure of it,” though the impulse to set the ancient text of the Catholic Mass for the Dead quite likely came from the passing of his father in 1885 and of his mother two years later. The score was completed early in 1888 and first heard, under the composer’s direction, at the Madeleine in Paris as part of a memorial service for Joseph Le Soufaché, one of the parishioners. This first version contained only five movements (Introit et Kyrie, Sanctus, Pie Jesu, Agnus Dei and In Paradisum), and was scored for a modest ensemble of divided violas and cellos, basses, harp, timpani and organ, with a part for solo violin in the Sanctus. Fauré prepared a new version of the score for a subsequent performance in 1893 that contained two additional movements (Offertorium, composed in 1889, and Libera me, originally written in 1877 as an independent composition for baritone and organ) and expanded the orchestration to include horns and trumpets. In preparation for the work’s publication by Hamelle in 1900, it was re-scored for full orchestra to make it available for concert as well as liturgical performances, though the orchestration was probably done not by Fauré but by his student Jean-Jules Roger-Ducasse. This final version was first heard at the Trocadéro Palace in July 1900 conducted by Paul Taffanel.

Unlike the grand, dramatic, sometimes tumultuous settings of the Mass for the Dead by Berlioz and Verdi, Fauré’s Requiem is intimate in scale and consoling in content. Fauré, perhaps under the influence of the Cecilian Movement, which sought a personal, uncomplicated and direct manner of religious expression, chose to omit the text of the Dies irae, the searing Medieval poem that so chillingly paints the terrors of the “Day of Wrath”—the Last Judgment. The composer’s pupil and friend Charles Koechlin believed that “the indulgent and fundamentally good nature of the master had as far as possible to turn from the implacable dogma of eternal punishment.” The composer himself wrote, “It has been said that my Requiem does not express the fear of death; someone has even called it a lullaby of death. But it is thus that I see death: as a happy deliverance, an aspiration toward happiness above....” In a letter of April 3, 1921 to René Fauchois, he further explained, “Everything I managed to entertain in the way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which moreover is dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest.” The grace, restraint and calm Hellenic beauty that characterize Fauré’s best music find their perfect realization in this work, about which the celebrated pedagogue Nadia Boulanger said, “Nothing purer or clearer in definition has been written. No external effect alters its sober and rather severe expression of grief, no restlessness troubles its deep meditation, no doubt stains its gentle confidence or its tender and tranquil expectancy.”

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda