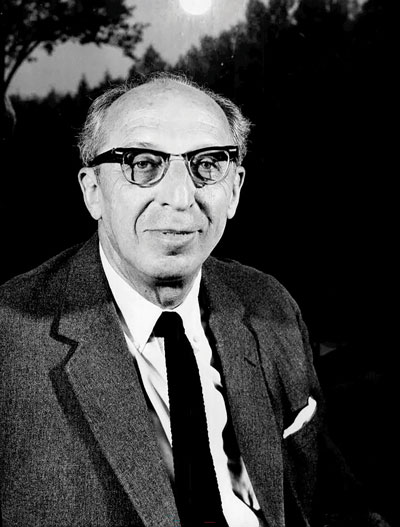

Aaron Copland

Born: November 14, 1900, New York City

Died: December 2, 1990, North Tarrytown, New York

Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo

- Composed: 1942

- Premiere:

- Ballet: October 16, 1942 at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, Franz Allers conducting, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

- Suite: May 28, 1943 in Boston, Arthur Fiedler conducting the Boston Pops Orchestra (three episodes only); full suite June 22, 1943 in New York, Alexander Smallens conducting the New York Philharmonic.

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First & Most Recent CSO Subscription: March 1962, Haig Yaghjian conducting

- Most Recent: July 1998 as part of a regional tour of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, John Morris Russell, conducting

- Recording: Aaron Copland: The Music of America (Cincinnati Pops) released in 1997 Erich Kunzel conducting. Won a Grammy Award for Best Engineered Album, Classical.

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. 2 piccolos), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, slapstick, snare drum, suspended cymbals, triangle, whip, wood block, xylophone, harp, piano, celeste, strings

- Duration: approx. 18 minutes

Aaron Copland composed the music for Rodeo in 1942 based on a scenario developed by rising choreographer Agnes de Mille. She was the first American dancer commissioned by Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo—a descendent troupe of Serge Diaghilev’s earlier Parisian powerhouse—tasked with producing something characteristically American. For such a tall order, de Mille determined the only suitable composer could be the country’s most prominent. De Mille’s scenario, in its essence, is a simple love story: in Texas ranchland around the year 1900, a Cowgirl seeks love, trying all manner of strategies to woo the Head Wrangler while being courted herself by another ranch hand, redolent of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew. Although Copland was skeptical of producing another cowboy ballet after his Billy the Kid from 1938, he accepted de Mille’s proposal for the $1,000 commission. The resulting ballet includes a range of vernacular elements, from authentic dance movements to Copland’s incorporated folk tunes. Both dance and music were designed to infuse the work with realism, and, though the music has been more of a repertorial mainstay than the ballet’s original choreography, the whole reflects contemporaneous cultural tastes. Rodeo partook in a wider interest in Western frontier stories at the time, and indeed, de Mille’s very next project was choreographing the landmark musical Oklahoma! in collaboration with composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II (who attended Rodeo’s premiere). De Mille’s dream ballet for the show became especially influential on the next generation of musicals for its psychological richness.

Much of the original Rodeo remains intact in Copland’s refashioning of the ballet for the orchestral suite—the composer only eliminated around five minutes, primarily a section called “Ranch House Party” between what became the second (“Corral Nocturne”) and third (“Saturday Night Waltz”) episodes of the suite. Either paired with the staged drama or as standalone concert music, Rodeo is among Copland’s most famous and cherished scores, beloved for capturing a mythical American ethos.

The first episode of the suite, “Buckaroo Holiday,” raises the curtain on a scene in progress. The young Cowgirl seeks a love match, attempting to become familiar with the Head Wrangler by dressing and acting like a cowboy. As the cowboys do their best to show off, girls, including the Rancher’s Daughter, enter and flirt. The score reflects differences of character through musical style and mood changes meant to correspond to the rambunctious cowboys and delicate girls. This first episode employs the heaviest dose of folk tunes in the ballet, most prominently “If He’d Be a Buckaroo,” as well as “Sis Joe,” which the composer thought brimmed with rhythmic potential. Copland’s incorporation of these tunes and his general use of syncopated rhythms led some early listeners to disavow the score as a debasement of the art form. Copland certainly felt very differently, though he understood that his techniques were changing the sound of art music, having already composed extensively using vernacular musical sources from across the Americas and having infused folk elements into his score for Billy the Kid. By using folk tunes, Copland presents listeners with a question of how this music works: Is the folk music of “Buckaroo Holiday” diegetic—part of the characters’ world and something they can hear? Or is it non-diegetic—music only we as outsiders can perceive as part of the entertainment complex? At stake is the nature of our own experience in what we perceive, simultaneously familiar and otherworldly.

The second episode, “Corral Nocturne,” transitions from the titular rodeo scene to the evening’s dances. The Cowgirl wallows, lonely for companionship she has yet to win, while the Head Wrangler and Rancher’s Daughter share an evanescent pas de deux. For a moment, the Champion Roper shows interest in the Cowgirl. The music of the “Nocturne” floats atmospherically, starkly contrasting what precedes in “Holiday.” No longer do we hear any direct use of folk tunes or anything that strikes us as decidedly belonging to the characters’ world. Even with a pas de deux (a dance set piece of which Copland was apparently unaware when composing), this is non-diegetic music intended for the audience to understand the characters’ emotional states. Here, bucolic evocation supersedes rousing theme.

The third episode, “Saturday Night Waltz,” returns us very squarely to diegetic music with a type that is quintessentially lived and experienced in the world: dance music. The episode begins realistically with the sounds of strings tuning and buckling down for an evening’s entertainment. The dances begin, and amidst couplings and romantic felicitations, the Cowgirl and Champion Roper take center stage, moving the momentary encounter in the “Nocturne” one step further. Along the way, Copland makes use of the folk tune “I Ride an Old Paint” (“Houlihan”) as a lilting triple-time foundation.

The ballet’s most iconic episode, “Hoe-Down,” brings the drama to a close as the Cowgirl startlingly reveals her true identity, exchanging her cowboy’s clothing for a dress and hair bow. By the end of the scene, she woos her original beloved, the Head Wrangler, who approaches her only to be foiled as the Champion Roper swoops in to kiss her. A bevy of fiddle tunes populates the scene, including “McLeod’s Reel,” “Gilderoy,” “Tip Toe, Pretty Betty Martin” and, most famously, “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” the first full tune in the episode after a bracing opening outburst and jaunty vamp. Although the other episodes certainly convey realism in their musical evocations, “Hoe-Down” may be the most firmly grounded in musical practice, nearly indistinguishable from the rocketing virtuosity of string tunes at home in an evening of reels and quadrilles.

Although the narrative de Mille devised meanders, it follows her simple description: “The theme of the ballet is basic. It deals with the problem that has confronted all American women, from earliest pioneer times, and which has never ceased to occupy them throughout the history of the building of our country: how to get a suitable man.” The War-time context of the ballet’s creation strikes a note with the experiences of many Americans at a time when scores of the country’s men were joining efforts overseas and women temporarily took on “masculine” work outside the home, analogous to the Cowgirl’s male dress and acting. As dance scholar Lynn Garafola has described it, Rodeo celebrates the Cowgirl’s ability to keep up with, and even outdance, the boys, testimony to the hard extra-domestic work of the country’s women during the War. More generally, the comedic piece presents an upbeat nostalgic view of America prior to its mid-20th century cultural and political acrimonies, a quite different tone from the nuanced sobrieties of Billy the Kid, Appalachian Spring or the opera The Tender Land.

Beyond Rodeo’s reflection of its historical moment and earthy roots, there is something exceptional about witnessing this dramatic piece divorced from one of its chief components, the visual element of ballet. It is no coincidence that audiences often refer to attending an opera, ballet or spoken play as “seeing” it, as opposed to hearing it; the visuals are vital, perhaps as central as any other element. So when we have the opportunity to hear the music of an opera or ballet in concert—that is, not staged with sets, costumes or choreography—our imaginations spark in different ways. The music asks us to imagine who is whom in the musical portrayals, an especially mercurial pursuit for Rodeo in light of the Cowgirl’s deceptions. In the concert hall, we might focus more on the music than we would in a full production, to be sure, but the experience is akin to reading a book before seeing the movie version. Our own life experiences generate our own ideas of what this could look like. Authors and readers in the 19th century designated certain poems and plays intended to be read and only “staged” in the mind as “mental theatre,” opening up endless possibilities that might be unavailable to us when the look of the performance is presented in production. In this way, hearing Rodeo in concert without seeing it staged and danced gives audiences the chance to take charge and, not unlike the libretto’s characters, let their passions blossom. Rodeo seems particularly vivid on this front, and the immediate experience of attending a performance of the music or hearing a recording reminds us of the score’s particular power. It has taken an iconic status outside its original context, evocatively deployed for advertising (“Beef. It’s what’s for dinner.”), film (Spike Lee’s 1998 He Got Game), and many other uses. Whether by stirring imaginations or patriotic fervor, Copland’s score towers in musical culture as an iconic and steadfast symbol of American sound.

—Jacques Dupuis