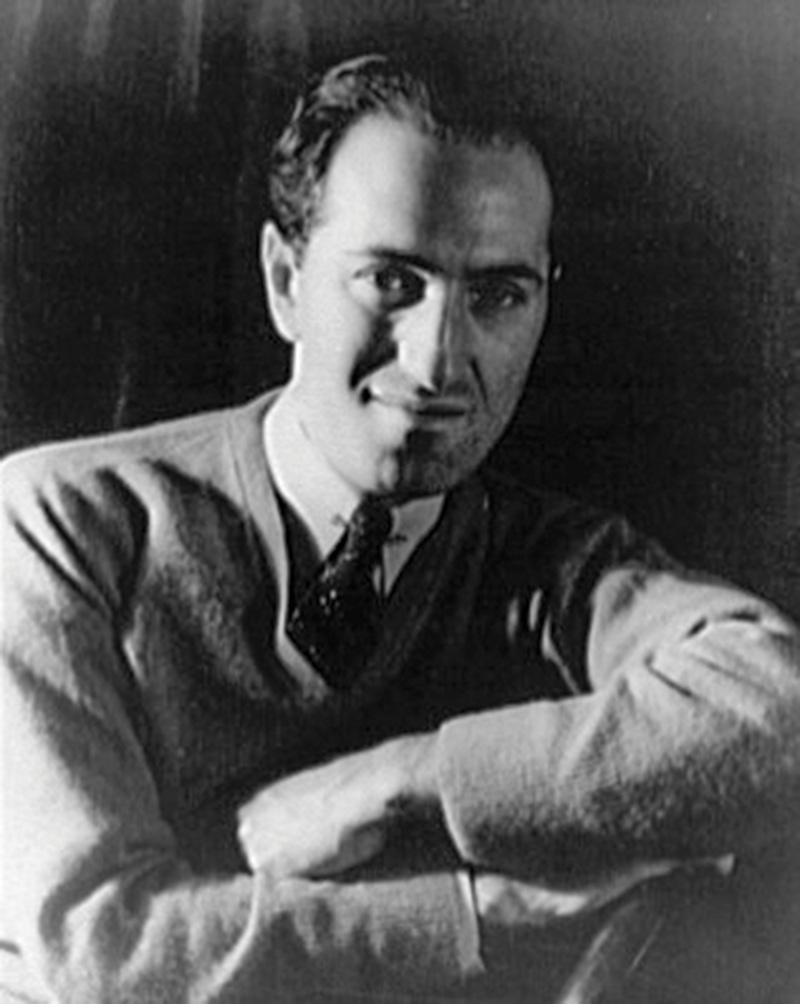

George Gershwin

Born: September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, New York

Died: July 11, 1937, Hollywood, California

Rhapsody in Blue

- Composed: 1924; orch. by Ferde Grofé 1942; transcribed for banjo solo by Béla Fleck 2020–23

- Premiere: February 12, 1924 in New York, conducted by Paul Whiteman, with the composer as soloist; Béla Fleck arrangement for banjo premiered September 9, 2023 by the Nashville Symphony, conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero with Fleck as soloist.

- CSO Notable Performances (original piano version):

- First: March 1927, Fritz Reiner conducting; George Gershwin, piano (this concert also included Gershwin’s Concerto in F, also with the composer as soloist)

- Most Recent CSO Subscription: January 2020, Louis Langrée conducting, with the piano solo part being played on a Yamaha Disklavier piano digitally rendered from Gershwin’s piano roll.

- Most Recent: January/February 2020 Cincinnati Pops concert, John Morris Russell conducting, with The Marcus Roberts Trio (pianist Marcus Roberts, upright bass Rodney Jordan and drum set Jason Marsalis).

- Recording: Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris released in 1981, Erich Kunzel conducting; Eugene List, piano

- Instrumentation: solo banjo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 3 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, strings

- Duration: approx. 16 minutes

Orchestrated by Ferde Grofé

Born: March 27, 1892 in New York City

Died: April 3, 1972 in Santa Monica, California

Transcribed for banjo by Béla Fleck

Born: July 10, 1958 in New York City

For George White’s Scandals of 1922, the 24-year-old George Gershwin provided something a little bit different—an opera, a brief, somber one-acter called Blue Monday (later retitled 135th Street) incorporating some jazz elements that White cut after only one performance on the grounds that it was too gloomy. Blue Monday, however, impressed the show’s conductor, Paul Whiteman, then gaining a national reputation as the self-styled “King of Jazz” for his adventurous explorations of the new popular music styles with his Palais Royal Orchestra. A year later, Whiteman told Gershwin about his plans for a special program the following February in which he hoped to show some of the ways traditional concert music could be enriched by jazz, and he suggested that the young composer provide a piece for piano and jazz orchestra. Gershwin, who was then busy with the final preparations for the upcoming Boston tryout of Sweet Little Devil and somewhat unsure about barging into the world of classical music, did not pay much attention to the request until he read in The New York Times on New Year’s Day that he was writing a new “symphony” for Whiteman’s program. After a few frantic phone calls, Whiteman finally convinced Gershwin to undertake the project, a work for piano solo (to be played by the composer) and Whiteman’s 22-piece orchestra—and then told him that it had to be finished in less than a month. Themes and ideas for the new piece immediately began to tumble through Gershwin’s head, and late in January, only three weeks after it was begun, the Rhapsody in Blue was completed.

The premiere of the Rhapsody in Blue—New York, Aeolian Hall, February 12, 1924—was one of the great nights in American music. Many of the era’s most illustrious musicians attended, critics from far and near assembled to pass judgment, and the glitterati of society and culture graced the event. Gershwin fought down his apprehension over his joint debuts as serious composer and concert pianist, and he and his music had a brilliant success. “A new talent finding its voice,” wrote Olin Downes, music critic for The New York Times. Conductor Walter Damrosch told Gershwin that he had “made a lady out of jazz,” and then commissioned him to write the Concerto in F. There was critical carping about laxity in the structure of Rhapsody in Blue, but there was none about its vibrant, quintessentially American character or its melodic inspiration, and it became an immediate hit, attaining (and maintaining) a position of popularity almost unmatched by any other concert work of a native composer.

■ ■ ■

Rhapsody in Blue has appeared in varied instrumental settings since its inception in 1924, appearing almost simultaneously in Gershwin’s versions for one and two pianos and for piano soloist with jazz orchestra by Ferde Grofé, Paul Whiteman’s arranger; two years later, Grofé scored it for “theater” (chamber) orchestra and, in 1942, for full symphony orchestra, the version in which it is best known. The music’s popularity and instrumental flexibility have also invited a wide range of arrangements over the years—from organ to concert band, from saxophone quartet to unaccompanied marimba, with adaptations of the solo part for trumpet, harmonica, two clarinets and other instruments—and, in observance of the centennial of the Rhapsody’s premiere, banjo wizard Béla Fleck adapted the solo piano part for his instrument.

Fleck first heard the Rhapsody in Blue at age seven in his native New York City, when an uncle took him to a screening of the eponymous 1945 biopic that starred Robert Alda (Alan Alda’s father) as Gershwin and used the Rhapsody as its finale. “The movie had an incredible impact on young me,” Fleck recalled, “and the Rhapsody in Blue in particular blew me away. Over the years, I’ve checked in with Rhapsody regularly and always found that it had that same compelling effect on me,” so he added it to the “bucket list” of pieces he wanted to explore on his instrument. That opportunity arrived with the Covid pandemic lockdown in 2020, when concert life abruptly ceased and performers sought productive ways to use their unexpected free time. Fleck studied Gershwin’s piano score “one measure at a time, just to see if it was even remotely possible on the banjo…. Technically,” he concluded, “it would not be easy, but some kind of possible.”

Since Gershwin’s piano writing was dense, complex and technically challenging, an immediate problem for Fleck was that his instrument could only play three notes simultaneously, versus the piano’s potential 10, and did so across a much wider range. “It’s a very two-handed part,” Fleck explained. “There are lots of things that go in opposite directions, with both hands working really hard. And I simply couldn’t do them on the banjo. It took three separate banjo staves entered into a music notation application for me to even understand what the piano part was doing. I worked on each measure over the course of the year to accommodate the banjo’s range and limitations, and then still had to judge whether the piece was good enough as a banjo feature, doing without all of the things that a piano could do. Finally, I decided that if George was OK with Larry Adler playing it on the harmonica [in 1934], I think he’d probably be OK with my version.”

With the Rhapsody’s solo part carefully tailored to his own instrument, Fleck integrated it into Grofé’s 1942 arrangement for full orchestra and premiered the piece on September 9, 2023 with the Nashville Symphony, conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero. Fleck recorded his arrangement the following February with the Virginia Symphony Orchestra and conductor Eric Jacobsen and timed the release to coincide with the exact centenary of the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue—February 12, 2024.

For those familiar with Grofé’s 1942 arrangement of the Rhapsody in Blue for piano with full orchestra, Fleck’s arrangement presents the piece in a different expressive light. Since the Rhapsody is, among many things, a showcase for the breathtaking technique of a virtuoso pianist (which Gershwin was universally attested to be), that aspect is inherent in most performances. The banjo, however, cannot match the piano in its power, speed or cascades of notes, so Fleck’s version is performed slower than customary (18:50 for his recording, ca. 16:00 for published editions and most recordings). The resulting music is more lean, spacious and intimate, allowing many of the score’s details to be heard more clearly and to better appreciate the remarkable craftmanship that the 25-year-old George Gershwin brought to the Rhapsody in Blue, his first composition for the concert hall.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda