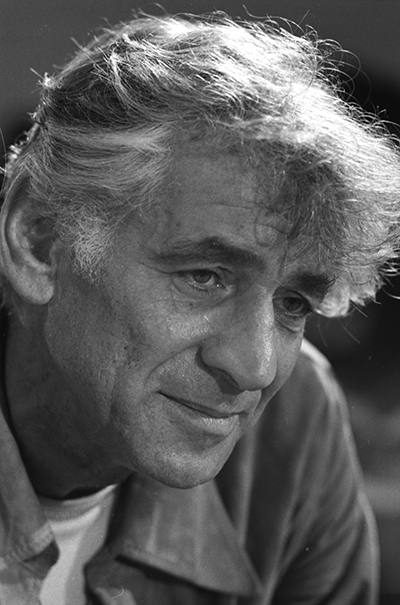

Leonard Bernstein

Photo by Marion S. Trikosko, 1971, courtesy of the Library of Congress and The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc.

Born: August 25, 1918, Lawrence, MA

Died: October 14, 1990, New York, NY

Chichester Psalms

- Composed: February–June 1965

- Premiere:

- World premiere: July 15, 1965, New York Philharmonic Hall, Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic and Camerata Singers

- Original version with an all-male chorus and the treble parts being performed by boys : July 31, 1965, Chichester Cathedral with the combined choirs of Winchester, Salisbury and Chichester cathedrals

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: March 1967 in Fort Thomas, KY, Erich Kunzel conducting, with the Highlands High School Chorus

- First CSO Subscription: November 1974, Erich Kunzel conducting, with Scott Moening, boy soprano; Northern Kentucky State College Chamber Singers & Concert Choir; and Miami University Choraliers, A Cappella Singers & Men’s Glee Club

- Most Recent CSO Subscription: September 1997, Jesús López Cobos conducting, with Tyler Evick, boy soprano and the May Festival Chorus (Robert Porco, director)

- Most Recent CSO Performance: May 2018, Juanjo Mena conducting the CSO, May Festival Chorus, May Festival Youth Chorus and countertenor John Holiday as part of the May Festival

- Notable: May 1967, Robert Shaw conducting the CSO, 11 local high school choirs and Kevin O’Connell, boy soprano, as part of the May Festival

- Instrumentation: boy soprano solo, SATB chorus, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, bongo drums, chime, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, rasping stick, slapstick, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tambourine, temple blocks, triangle, whip, wood block, xylophone, 2 harps, strings

- Duration: approx. 19 minutes

Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms begins exuberantly with an arresting choral exhortation in Hebrew on the text of Psalm 108: “Awake, psaltery and harp: I will rouse the dawn!” The singers continue with more verve, singing Psalm 100, “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord all ye lands.” These opening strains introduce one of Bernstein’s most cherished and frequently performed works, reflecting the composer’s own words: “It is quite popular in feeling…and it has an old-fashioned sweetness along with its more violent moments.” Indeed, throughout its approximately 20-minute duration, Bernstein’s description applies just as well to the music as it does to the text, in which the composer couches the sacred texts in a wide range of musical atmospheres and effects to shepherd the audience through the Psalms’ nuanced and personal sensitivities.

Bernstein completed Chichester Psalms in the middle of his lauded tenure as the New York Philharmonic’s music director, a position he held from 1958 to 1969. As he was vetted for the position, he claimed that it appealed to him as a way of simplifying his life and finding more settled roots for him and his wife, Felicia, to raise their family. But Bernstein was busier than ever, not only growing his family but also carrying on as a public intellectual with lectures, television broadcasts and books; guest conducting the globe’s leading ensembles; touring and recording prolifically with the Philharmonic; and moving the orchestra to its new home in Lincoln Center. Despite his intent to continue composing apace (the early 1950s were productive), his orchestra tenure all but forced him to cease writing music altogether. Between 1957 when West Side Story premiered and 1971 when his monumental MASS debuted, the only substantial works he composed were Symphony No. 3, Kaddish (1963) and Chichester Psalms. Later in life, Bernstein regretted not having composed more, and this period exemplifies the potential drawbacks of being the rare truly polymathic musician. Posterity, however, recognizes these two works as towering achievements and among his most personally meaningful.

In search of time to compose amid his grueling Philharmonic schedule, Bernstein took a sabbatical for the 1964–65 season, intending to complete a new stage musical on Thornton Wilder’s play, The Skin of Our Teeth. Although he abandoned the work after half a year’s work with collaborators, Bernstein salvaged the sabbatical to produce Chichester Psalms, a commission he had received in December 1963 from Rev. Walter Hussey, the Dean of Chichester Cathedral, Sussex. Bernstein completed the work in the spring, primarily from February to May, and finished the orchestrations soon after. As he had done elsewhere, Bernstein used his sway to introduce the work away from its commissioners, and, in July 1965, he conducted the piece’s world premiere with the New York Philharmonic and Camerata Singers. Two weeks later, the work debuted at the choral festival for which it was commissioned at Chichester Cathedral, sung by members of the combined Winchester, Salisbury and Chichester cathedral choruses.

To some degree, Chichester acts as a manifesto of Bernstein’s aesthetic positions at the time. He was skeptical, but not entirely averse, to contemporary composition techniques, occasionally incorporating 12-tone methods and extraordinary degrees of dissonance (the latter even heard in Chichester). But in a humorous verse description of his sabbatical, the composer cast a sardonic eye at the century’s newest musical developments, writing:

For hours on end I brooded and mused

On materiae musicae, used and abused;

On aspects of unconventionality,

Over the death in our time of tonality,

Over the fads of Dada and Chance,

The serial strictures, the dearth of romance,

“Perspectives in Music,” the new terminology,

Physiomathematomusicology;

Pieces called “Cycles” and “Sines” and “Parameters”—

Titles too beat for these homely tetrameters;

Pieces for nattering, clucking sopranos

With squadrons of vibraphones, fleets of pianos

Played with the forearms, the fists and the palms

—And then I came up with the Chichester Psalms.

These psalms are a simple and modest affair,

Tonal and tuneful and somewhat square,

Certain to sicken a stout John Cager

With its tonics and triads and E-flat major.

But there it stands—the result of my pondering,

Two long months of avant-garde wandering—

My youngest child, old-fashioned and sweet.

And he stands on his own two tonal feet.

Even if his own tastes broke from many of his most academically girded colleagues, no one could rightly accuse Bernstein of ignorance, given the laundry list he produced here. The actual music of Chichester Psalms underscores the verses’ ironic flair. Many of the piece’s rhythms are decidedly un-square, often including constant but difficult-to-dance-to groupings of notes in sevens, fives and 10s, as opposed to dance music’s more favored two-, three- and four-note groups. “Tonics” and “triads” are scattered across the score, but “E-flat major” is difficult to find.

Beyond debates of musical aesthetics, Chichester Psalms hails from a period in which Bernstein remained in touch with social and political current events. Symphony No. 3’s orchestral score and declaimed text speak to issues of the day, consistent with the composer’s social engagement in the surrounding decades, portrayed in Tom Wolfe’s firebrand “Radical Chic” new journalism piece. And amid the composition of Chichester Psalms, Bernstein traveled to Alabama in a show of support for the Selma to Montgomery civil rights marches.

Following the opening proclamation and onset of foot-tapping drive, the first movement plays out in raucous celebration. Not long before the triumphant ending, the orchestra fragments into striking clock-like music that prepares a brief section for vocal soloists. As Bernstein scholar Paul Laird has written, significant portions of Chichester Psalms were recouped from what Bernstein originally wrote for The Skin of Our Teeth, including parts of this opening movement, indicative of the “popular feeling” Bernstein referenced.

During preparatory phases on the project, Rev. Hussey had asked the composer, “I think many of us would be very delighted if there was a hint of ‘West Side Story’ about the music.” Bernstein more than obliged, and for the middle of the second movement, he refashioned a highly rhythmic, percussive section cut from the Prologue of West Side Story (“Mix—make a mess of ‘em!”) to set Psalm 2, verse 1, “Why do the nations rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?” The adaptation works well, and in Chichester Psalms it is marked as an abrupt interruption of the sweeter Psalm 23 text with which the movement opens, sung by a soloist. The different sweet and more aggressive styles layer over, across and through one another, and the movement closes with a fragile return to the placid opening, momentarily disturbed by the aggressive percussion. The juxtaposition may be startling, and not only on musical grounds; the anxieties allayed by God in Psalm 23 seem to burst through in Psalm 2. Perhaps the bluesy coloring of the Psalm 23 melody conveys that complexity? Regardless, Bernstein’s keen eye for counterpoint across different lines, both musical and linguistic, is apparent.

The final movement opens with string music that is the most strident in the whole work. It soon settles in underneath a paired harp and muted trumpet (marked lontano, or “distant”) duet, a set of contrasts that turn the mood from the anxieties of the previous movement toward the humble supplications of Psalms 131 and 133. The chorus follows with its own ruminations on the nurturing spirit of mothers for their children, and soon the strings return, this time with lullaby-like melodies that overcome the tension of the beginning. The piece concludes as vocal soloists float heavenward with Psalm 131, and an unaccompanied chorus answers seamlessly by singing the beginning of Psalm 133. The musical character matches the Psalm’s call to unity, leaving listeners to ponder its message, as relevant to the present day as it was for Bernstein’s time.

—Jacques Dupuis