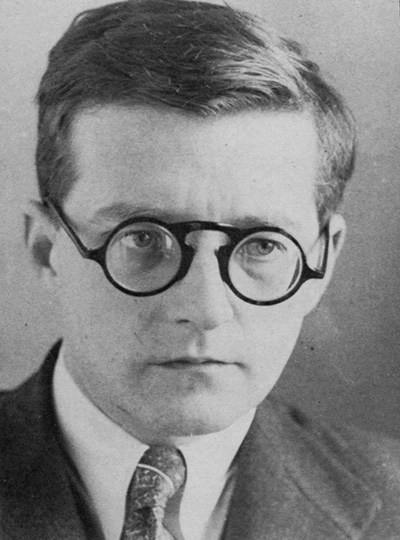

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Died: August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia

Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Op. 60, Leningrad

- Composed: 1941

- Premiere: March 5, 1942 by Samuil Samosud and the orchestra of Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: January 1943, Eugene Goossens conducting

- Most Recent: February 2018, Juanjo Mena conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. alto flute and piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets (incl. E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 6 trumpets, 6 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, snare drums, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, xylophone, 2 harps, piano, strings

- Duration: approx. 70 minutes

Shostakovich began work on his Seventh Symphony four weeks after Hitler’s troops invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. He worked at feverish speed and finished the 30-minute first movement in about a month. The second and third movements were written after the blockade had begun, while Shostakovich was serving on the fire-fighting brigade at the Leningrad Conservatory. He frequently had to interrupt his work to escort his family to the bomb shelter during air raids. Many people in Leningrad (as St. Petersburg was known during Soviet times) knew that Shostakovich was working on a new symphony even as food was becoming extremely scarce in the city, and they were gratified to know that the arts were still alive in spite of everything. (A 1965 book about this difficult period bears the title But the Muses Were Not Silent.)

At the end of September, Shostakovich, his wife and two young children were evacuated from the besieged city. They were flown to Moscow and, two weeks later, traveled by train to the city of Kuibyshev (now Samara) on the Volga River—a 600-mile journey that, amidst the wartime chaos, took a whole week to complete. The Shostakoviches remained in Kuibyshev for a year and a half before they were allowed to move to Moscow. It was in Kuibyshev that the composer finished the symphony, and there it was premiered by Samuil Samosud and the orchestra of Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, which had also been evacuated there, on March 5, 1942. A second performance in Moscow followed at the end of March, but the concert that really made musical history took place in Leningrad on August 9, 1942, 11 months into a blockade that was going to continue for almost another year and a half. Overcoming difficulties beyond belief, conductor Karl Eliasberg assembled an orchestra of starving, exhausted musicians to play for a packed hall of starving, exhausted audience members, many of whom wept openly as they listened to the music. As Solomon Volkov writes in his 1995 book St. Petersburg: A Cultural History, “Leningraders wept for their fate and that of their city, slowly dying in the grip of the most ruthless blockade of the 20th century.” The concert served Stalin as a propaganda ploy, to show that the city could never be defeated, but this hardly mattered to those who were witnessing this historic moment.

The political dimension of the event could hardly be ignored, and the new work, held up in Russia as a symbol of heroism, also made a sensation in the West. The adventure-filled story of how the manuscript reached the United States was itself made into a movie: the score was microfilmed, flown to Tehran, driven from there to Cairo and finally flown to New York via Casablanca. A whole crew of photographers worked for 10 days to create paper prints of the 252-page score from which conductors could work and parts could be made. Some of the most prominent maestros in the U.S., including Serge Koussevitzky, Artur Rodziński and Leopold Stokowski, vied for the jus primae noctis (“the right to the first night”), to quote the irreverent expression conductor-musicologist Nicolas Slonimsky used when he told the story. The race was finally won by Arturo Toscanini, who led the American premiere on July 19, 1942. The NBC broadcast was referred to in Newsweek as “the premiere of the year,” and Time magazine, not to be outdone, carried a drawing of the composer wearing a fire-helmet on its July 20 cover with the caption “Fireman Shostakovich–Amid bombs bursting in Leningrad he heard the chords of victory.”

A composer who was very close to me once said, “I never ask myself what music to write, only what music wants to be written by me.” What music “wanted to be written” by Shostakovich under such extreme circumstances? First of all, it was crucial for the composer to be immediately understood by the listeners whose destinies were so inextricably linked to his own. He went out of his way to write simply, with melodies built on scales and symmetrical, four-square rhythms. He had to portray tragedy and turmoil while also offering comfort and holding out hope for a better future. Accessibility and optimism were, of course, qualities the Soviet authorities were constantly demanding of composers and, several times during his career, Shostakovich ran afoul of the Party apparatchiks on those very points. But this time, the composer could sincerely and honestly identify with the official requirements.

Without a doubt, the most famous segment of the symphony is the one depicting the approaching Nazis. It arrives after a confident opening and a dream-like ethereal section suggesting a peaceful idyll. Then, the march begins, pianissimo at first, and repeated in identical fashion no fewer than 11 times, in a gradual crescendo that inevitably invited comparisons with Ravel’s Boléro. Shostakovich commented, “Idle critics will no doubt reproach me for imitating Ravel’s Boléro. Well, let them, for this is how I hear the war.”

The persistent repeats were not the only extraordinary feature of this section. Another was the intentional triviality of the theme repeated. The very vacuity of the theme qualifies it as a parody of an imaginary song the Nazis might have marched to. (If this is true, the parody of this passage in the fourth movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra is the parody of a parody, although Bartók may not have realized that.)

After reaching a monumental climax, the war theme gradually dissolves and the idyllic initial materials return. A lyrical bassoon solo has been interpreted as a dirge for those who died in the war. Ultimately, all that remains of the war theme is a distant echo at the end of the movement.

At first, Shostakovich intended to let this movement stand by itself as a symphonic poem. When he changed his plans and wrote three more movements to complete the classical symphony scheme, he faced the obvious problem of where to go after such a strong opening statement. According to his own words, the two middle movements were meant to “ease the tension” and the finale to portray “victory.” Yet the case is more complex: the middle movements are far from tension-free and the finale reaches victory with considerable difficulty and in a rather circuitous way.

The second movement, originally called “Reminiscences,” starts out as a gentle allegretto, with long melodic lines unfolding over a characteristic rhythmic accompaniment. Yet the shrill sound of the piccolo clarinet is the harbinger of new conflicts: the middle section, in the words of commentator Robert Dearling, is “full of the most appallingly harrowing devices.” A modified recapitulation follows. The main theme, played by the solo oboe at the beginning of the movement, is now given to the bass clarinet. The extreme low register lends an eerie quality to the eminently lyrical melody.

The third movement is, in Shostakovich’s words, the “dramatic center of the whole work.” Described as a tribute to “Our country’s wide spaces” in the official program at the time, it was (and is) widely perceived as a lament for the victims of the war. After a few introductory wind chords, the violins make a solemn proclamation. The solo flute’s slowly unfolding melody evolves into an agitated dramatic statement that eventually subsides to prepare the return of the quiet and solemn music we heard earlier.

The finale, as commentator Hugh Ottaway once observed, “is by no means the barn-storming type of movement that a vision of victory might seem to suggest.” Shostakovich’s optimism is not the cheap socialist-realist variety promoted by the authorities. An enigmatic opening and an extended stormy passage, contradicting the idea of victory with its tragic C-minor tonality, are followed by a lengthy section in a relatively slow tempo (“moderato”), another possible song of mourning for the victims. The triumphant conclusion doesn’t arrive until the very end, with the recapitulation of the first movement’s opening C-major theme. Now at last the victory is complete as the majestic fanfares take over the entire orchestra in a grandiose triple fortissimo.

■ ■ ■

Abram Gozenpud (1908–2004), an eminent Russian scholar of music and literature, pointed out an interesting parallel between the symphony and a passage in one of Shostakovich’s favorite novels:

Shostakovich, like Dostoyevsky, shows how evil is born, and how what appears to be harmless in origin can turn into something dangerous and destructive. In The Possessed, Lyamshin improvises on the piano and combines “The Marseillaise” with the sentimental song “Ach, mein lieber Augustin.” Gradually this harmless little song changes its character and acquires a threatening note; it starts to rage and rampage monstrously and terrifyingly.

In the first movement of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony the harmless marching song gradually acquires the force of a hurricane which blows everything from its path. […] It seemed to me that the idea behind the conception of the central episode in the Symphony’s first movement shares a certain similarity with Lyamshin’s improvisation.

(Published in Elizabeth Wilson, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered. Princeton University Press, 1994.)

In this connection, it is worth mentioning that one of Shostakovich’s last works, Four Verses of Captain Lebyadkin, Op. 146 (1974), was a setting of poems from The Possessed (a novel also known in English as Devils).

—Peter Laki